ChatGPT Is Causing a Stock-Market Ruckus

Investors race to assess the rise of artificial intelligence as a possible ‘iPhone moment’

The rise of artificial intelligence is taking the tech world by storm. The technology is also making waves on Wall Street.

It is early days for so-called generative AI, a form of artificial intelligence that can conjure original ideas in the form of text, video or other media. But the tool has caused a stir in companies, schools, governments and the general public for its ability to process massive amounts of information and generate sophisticated content in response to prompts from users.

Big technology companies are investing billions of dollars in the technology. Startups are raising cash and trying to develop business models using AI at a rapid pace.

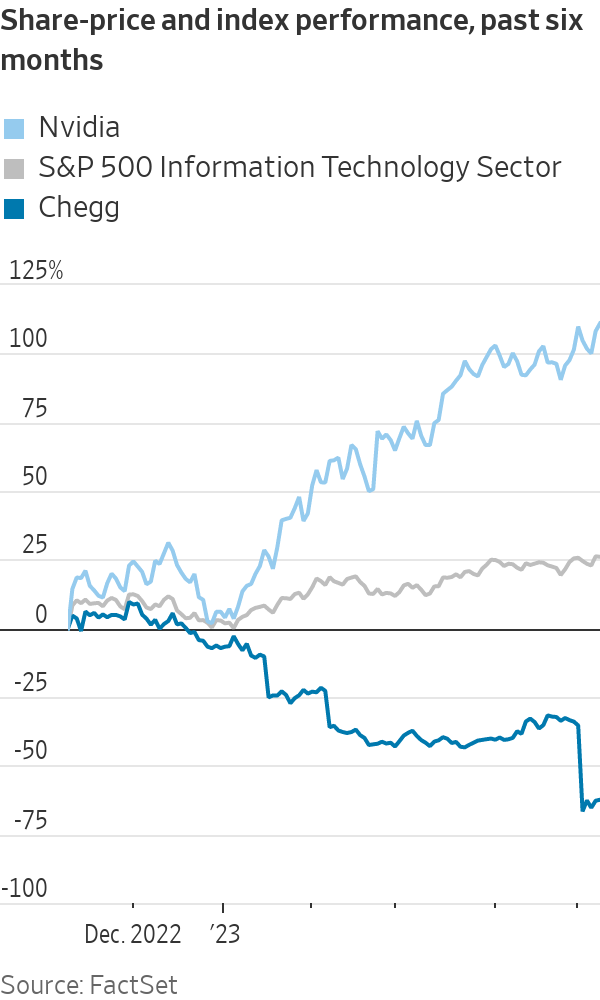

Investors are gauging the extent to which AI’s arrival will upend companies, industries and contemporary business practices—and placing bets accordingly. That has sent stocks swinging wildly in both directions: Chip maker Nvidia’s shares are surging, while shares of study-materials company Chegg have plummeted.Enthusiasm for the potential of AI is one reason big tech companies are among this year’s strongest performers.

There is little doubt that generative AI chatbots are popular. ChatGPT reached 100 million users in two months, the fastest app on record, analysts at Goldman Sachs said in a research note. In comparison, TikTok took nine months to reach that milestone, while Instagram took 30.

“We view AI as huge, and we’ll continue weaving it in our products on a very thoughtful basis,” Apple Chief Executive Tim Cook said last week on a conference call with analysts.

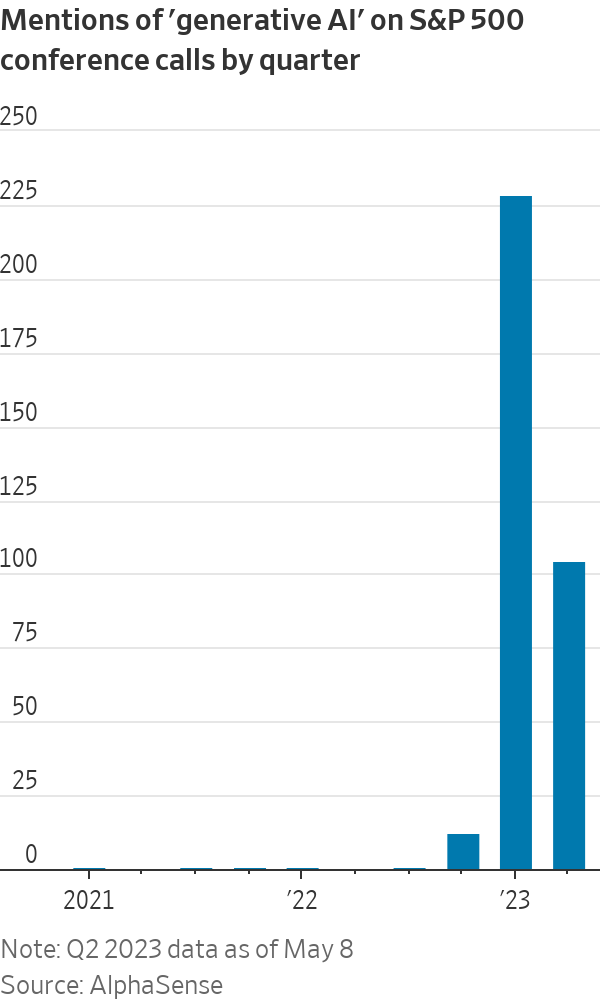

Apple isn’t alone. There have been more than 300 mentions of “generative AI” on company conference calls worldwide so far this year, according to data from AlphaSense. The phrase barely garnered a mention before 2023.

Major health systems are experimenting with AI to see whether the technology can help boost the productivity of their medical staffs. Entrepreneurs and venture-capital investors hope generative AI will revolutionise businesses from media production to customer service to grocery delivery. Even Coca-Cola told investors it is experimenting with the technology.

Some investors wonder whether generative AI is the latest tech with the potential to disrupt entire industries. The dawn of online streaming spelled the end of home-video-rental companies such as Blockbuster, while cameras on phones helped render photo processing obsolete and helped spark Apple’s rise and Kodak’s decline.

Artificial intelligence is “almost certainly overhyped in its initial implementation,” said Michael Green, chief strategist at Simplify Asset Management. “But the longer-term ramifications are probably greater than we can imagine.”

Microsoft has added nearly $500 billion in market value since the tech giant announced a $10 billion investment in startup OpenAI, developer of ChatGPT, in January. Shares of Nvidia, which makes chips needed to power the chatbots, have risen 96% so far this year. Google parent Alphabet shed $100 billion in market value in a single day earlier this year after its chatbot Bard underwhelmed investors, though those losses quickly reversed.

Alphabet shares are up 22% this year.

Those moves might prove ephemeral as the technology’s power becomes clearer, said Daniel Morgan, senior portfolio manager at Synovus Trust. “The most difficult thing to ascertain is, what is going to be the impact of all that spending to these companies on revenues and profits?” His fund owns shares of Microsoft, Alphabet and Nvidia.

The flurry of investor interest has pushed valuations higher. Nvidia trades at 164 times its past 12 months of earnings, according to FactSet. Microsoft and Alphabet trade at 33 times and 24 times, respectively.

Portfolio managers said the race to understand the implications of AI’s emergence is essential, both to invest in the technology’s winners and to avoid its eventual losers. Shares of Chegg fell 48% last week after the study-materials company said that the rise of ChatGPT was harming its ability to attract new customers.

“You just don’t know all the knock-on effects,” said Will Graves, chief investment officer at Boardman Bay Capital Management. “If this really is an iPhone moment, nobody saw that Uber was coming out of the iPhone to hammer the taxi industry.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.