Germany Is Losing Its Mojo. Finding It Again Won’t Be Easy.

Europe’s biggest economy is sliding into stagnation, and a weakening political system is struggling to find an answer

BERLIN—Two decades ago, Germany revived its moribund economy and became a manufacturing powerhouse of an era of globalization.

Times changed. Germany didn’t keep up. Now Europe’s biggest economy has to reinvent itself again. But its fractured political class is struggling to find answers to a dizzying conjunction of long-term headaches and short-term crises, leading to a growing sense of malaise.

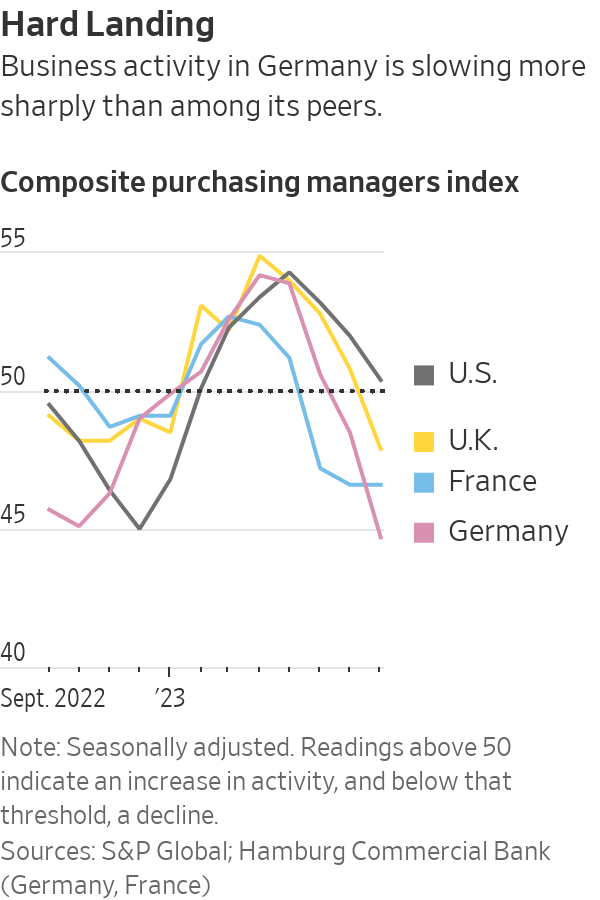

Germany will be the world’s only major economy to contract in 2023, with even sanctioned Russia experiencing growth, according to the International Monetary Fund.

Germany’s reliance on manufacturing and world trade has made it particularly vulnerable to recent global turbulence: supply-chain disruptions during the Covid-19 pandemic, surging energy prices after Russia invaded Ukraine, and the rise in inflation and interest rates that have led to a global slowdown.

At Germany’s biggest carmaker Volkswagen, top executives shared a dire assessment on an internal conference call in July, according to people familiar with the event. Exploding costs, falling demand and new rivals such as Tesla and Chinese electric-car makers are making for a “perfect storm,” a divisional chief told his colleagues, adding: “The roof is on fire.”

The problems aren’t new. Germany’s manufacturing output and its gross domestic product have stagnated since 2018, suggesting that its long-successful model has lost its mojo.

China was for years a major driver of Germany’s export boom. A rapidly industrialising China bought up all the capital goods that Germany could make. But China’s investment-heavy growth model has been approaching its limits for years. Growth and demand for imports have faltered.

Instead of Germany’s best customers, Chinese industries have become aggressive competitors. Upstart Chinese carmakers are competing with German incumbents such as VW that are lagging in the electric-vehicle revolution.

More broadly, the world has become less favourable to the kind of open trade that benefited Germany. The shift was expressed most clearly in then-President Donald Trump imposing tariffs not only on imports from China but also those of U.S. allies in Europe. The U.K.’s 2016 decision to leave the European Union and Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, leading to EU sanctions, also signaled a shift toward a more hostile environment for big exporters.

Germany’s long industrial boom led to complacency about its domestic weaknesses, from an ageing labor force to sclerotic services sectors and mounting bureaucracy. The country was doing better at supporting old industries such as cars, machinery and chemicals than at fostering new ones, such as digital technology. Germany’s only major software company, SAP, was founded in 1975.

Years of skimping on public investment have led to fraying infrastructure, an increasingly mediocre education system and poor high-speed internet and mobile-phone connectivity compared with other advanced economies.

Germany’s once-efficient trains have become a byword for lateness. The public administration’s continued reliance on fax machines became a national joke. Even the national soccer teams are being routinely beaten.

“We’ve kind of slept through a decade or so of challenges,” said Moritz Schularick, president of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy.

In March, one of Germany’s most storied companies, multinational industrial-gas group Linde, delisted from the Frankfurt Stock Exchange in favor of maintaining a sole listing on the New York Stock Exchange. The decision was driven in part by the growing burden of financial regulation in Germany. But also, Linde, whose roots go back to 1879, said it no longer wanted to be perceived just as German—an association that it believed was depressing its appeal to investors.

Germany today is in the midst of another cycle of success, stagnation and pressure for reforms, said Josef Joffe, a longtime newspaper publisher and a fellow at Stanford University.

“Germany will bounce back, but it suffers from two longer-term ailments: above all its failure to transform an old-industry system into a knowledge economy, and an irrational energy policy,” Joffe said.

“I think it’s important to remember that Germany is still a global leader,” German Finance Minister Christian Lindner said in an interview. “We’re the world’s fourth-largest economy. We have the economic know-how and I’m proud of our skilled workforce. But at the moment, we are not as competitive as we could be,” he said.

Germany still has many strengths. Its deep reservoir of technical and engineering know-how and its specialty in capital goods still put it in a position to profit from future growth in many emerging economies. Its labor-market reforms have greatly improved the share of the population that has a job. The national debt is lower than that of most of its peers and financial markets view its bonds as among the world’s safest assets.

The country’s challenges now are less severe than they were in the 1990s, after German reunification, said Holger Schmieding, economist at Berenberg Bank in Hamburg.

Back then, Germany was struggling with the massive costs of integrating the former Communist east. Rising global competition and rigid labor laws were contributing to high unemployment. Spending on social benefits ballooned. Too many people depended on welfare, while too few workers paid for it. German reliance on manufacturing was seen as old-fashioned at a time when other countries were betting on e-commerce and financial services.

After a period of national angst, then-Chancellor Gerhard Schröder pared back welfare entitlements, deregulated parts of the labor market and pressured the unemployed to take available jobs. The controversial reforms split Schröder’s Social Democrats, and he fell from power.

Private-sector changes were as important as government measures. German companies cooperated with employees to make working practices more flexible. Unions agreed to forgo pay raises in return for keeping factories and jobs in Germany.

Germany Inc. grew leaner. Meanwhile, the world was demanding more of what Germans were good at making, including capital goods and luxury cars.

China’s sweeping investments in industrial capacity powered the sales of machine-tool makers in Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg. VW invested heavily in China, tapping newly affluent consumers’ appetite for German cars.

Schröder’s successor, longtime Chancellor Angela Merkel, presided over years of growth with little pressure for further unpopular overhauls. Booming exports to developing countries helped Germany bounce back from the 2008 global financial crisis better than many other Western countries.

Complacency crept in. Service sectors, which made up the bulk of gross domestic product and jobs, were less dynamic than export-oriented manufacturers. Wage restraint sapped consumer demand. German companies saved rather than invested much of their profits.

Successful exporters became reluctant to change. German suppliers of automotive components were so confident of their strength that many dismissed warnings that electric vehicles would soon challenge the internal combustion engine. After failing to invest in batteries and other technology for new-generation cars, many now find themselves overtaken by Chinese upstarts.

A recent study by PwC found that German auto suppliers, partly through reluctance to change, have suffered a loss of global market share since 2019 as big as their gains in the previous two decades.

More German businesses are complaining of the growing density of red tape.

BioNTech, a lauded biotech firm that developed the Covid-19 vaccine produced in partnership with Pfizer, recently decided to move some research and clinical-trial activities to the U.K. because of Germany’s restrictive rules on data protection.

German privacy laws made it impossible to run key studies for cancer cures, BioNTech’s co-founder Ugur Sahin said recently. German approvals processes for new treatments, which were accelerated during the pandemic, have reverted to their sluggish pace, he said.

Germany ought to be among the nations winning from advances in medical science, said Hans Georg Näder, chairman of Ottobock, a leading maker of high-tech artificial limbs. Instead, operating in Germany is getting evermore difficult thanks to new regulations, he said.

One recent law required all German manufacturers to vouch for the environment, legal and ethical credentials of every component’s supplier, requiring even smaller companies to perform due diligence on many foreign firms, often based overseas, such as in China.

Näder said his company must now scrutinise thousands of business partners, from software developers to makers of tiny metal screws, to comply with regulation. Ottobock decided to open its latest factory in Bulgaria instead of Germany.

Energy costs are posing an existential challenge to sectors such as chemicals. Russia’s war on Ukraine has exposed Germany’s costly bet on Russian gas to help fill a gap left by the decision to shut down nuclear power plants.

German politicians dismissed warnings that Russian President Vladimir Putin used gas for geopolitical leverage, saying Moscow had always been a reliable supplier. After Putin invaded Ukraine, he throttled gas deliveries to Germany in an attempt to deter European support for Kyiv.

Energy prices in Europe have declined from last year’s peak as EU countries scrambled to replace Russian gas, but German industry still faces higher costs than competitors in the U.S. and Asia.

German executives’ other complaints include a lack of skilled workers, complex immigration rules that make it hard to bring qualified workers from abroad and spotty telecommunications and digital infrastructure.

“Our home market fills us with more and more concern,” Martin Brudermüller, chief executive of chemicals giant BASF, said at his annual shareholders’ meeting in April. “Profitability is no longer anywhere near where it should be,” he said.

One problem Germany can’t fix quickly is demographics. A shrinking labor force has left an estimated two million jobs unfilled. Some 43% of German businesses are struggling to find workers, with the average time for hiring someone approaching six months.

Germany’s fragmented political landscape makes it harder to enact far-reaching changes like the country did 20 years ago. In common with much of Europe, established centre-right and centre-left parties have lost their electoral dominance. The number of parties in Germany’s parliament has risen steadily.

Chancellor Olaf Scholz and his Social Democrats lead an unwieldy governing coalition whose members often have diametrically opposed views on the way forward. The Free Democrats want to cut taxes, while the Greens would like to raise them. Left-leaning ministers want to greatly raise public investment spending, financed by borrowing if needed, but finance chief Lindner rejects that. “We need fiscal prudence,” Lindner said.

Senior government members accept the need to cut red tape, as well as for an overhaul of Germany’s energy supply and infrastructure. But party differences often hold up even modest changes. This month the Greens lifted a veto of Lindner’s proposal to reduce business taxes only after they extracted consent for more welfare spending. As part of the deal, the government agreed to pass another law drafted by one of Lindner’s allies, Justice Minister Marco Buschmann, to trim regulation for businesses.

Scholz recently rejected gloomy predictions about Germany. Changes are needed but not a fundamental overhaul of the export-led model that has served Germany well throughout the post-World War II era, he said in an interview on national TV recently.

He cited the inflow of foreign investment into the microchips sector by companies such as Intel, helped by generous government subsidies. Scholz said planned changes to immigration rules, including making it easier to qualify for German citizenship, would help attract more skilled workers.

But Scholz has struggled to stop the infighting in his coalition. The government’s approval ratings have tanked, and the far-right populist Alternative for Germany party has overtaken Scholz’s Social Democrats in opinion polls.

“The country is being led by a bunch of Keystone Kops, a motley coalition that can’t get its act together,” Joffe said.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.