Japan Is Back. Is Inflation the Reason?

Deflation might be vanquished, but the payoff could be elusive

The Nikkei stock index recorded last week its first new high in 34 years, a fitting tribute to Japan’s re-emergence as a genuinely exciting economy.

It also comes amid mounting evidence that Japan has finally broken the hold of deflation. Inflation in January was 2.2%, the 22nd month above 2%. Wage growth has picked up too.

This appears to vindicate the economic consensus that deflation was a primary driver of Japan’s decades long malaise. But that conclusion might be premature. Proof of deflation’s harm has been elusive, and the benefits of low, positive inflation might be similarly subtle.

Consumers are often surprised to hear that deflation is supposed to be bad. In the U.S., where prices have risen steeply since 2021 , normal people, and even economists, wouldn’t object if they fell a bit.

The trouble arises when prices fall persistently, year in and year out, because wages, incomes and the prices of assets such as property tend to follow. Debtors struggle to repay loans and might slash spending or default, endangering the financial system. That is what happened in the U.S. when prices fell 27% from 1929 to 1933.

Even mild deflation can, in theory, inhibit growth. Central banks stimulate spending by lowering nominal interest rates below inflation to make the real—i.e., inflation-adjusted—cost of borrowing negative. That is almost impossible when inflation is itself negative.

The roots of deflation

Japan’s deflation began after its property and stock-market bubbles burst in the early 1990s. Ensuing losses at banks eroded their ability to lend. Inflation turned negative in 1999.

Western economists such as future Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke argued that curing deflation was essential to restoring Japan’s economic health. The Bank of Japan agreed, at first half heartedly and then wholeheartedly.

It used zero, then negative, short-term interest rates. Next came purchases of short-term, then long-term, government securities. Finally, the BOJ even bought shares in companies with newly created money to stimulate spending and raise inflation.

The BOJ only succeeded in bringing inflation up to around zero. It took the global supply chain shocks of the pandemic to finally push underlying inflation to 2%, the bank’s target .

Japan’s 25 years of zero to negative inflation was accompanied by one of the rich world’s lowest growth rates. Japanese deflation became a cautionary tale for other countries, most recently China, where prices are currently falling .

Yet proving that deflation was behind Japan’s problems is maddeningly hard. Arguably, it was more symptom than cause.

In the early 1990s, working-age population growth turned negative. This happened just as Japan’s post-World War II phase of catching up to other developed nations ended. Meanwhile, industry began moving production to lower-wage countries.

All this, plus the banking crisis, put structural downward pressure on prices, wages and growth.

Underlying performance

Adjusted for its shrinking population, however, Japan’s performance has been respectable. From 1991 to 2019, its output per hour worked rose 1.3% a year. This was slower than in the U.S. but comparable with Canada, France, Germany and Britain, and faster than Italy or Spain, according to the economists Jesús Fernández-Villaverde, Gustavo Ventura and Wen Yao.

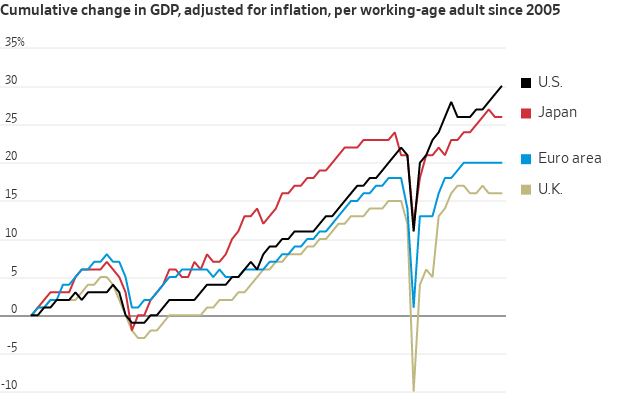

Since 2019, output per working-age person rose 7% in the U.S., 5% in Japan, 2% in the eurozone and zero in Britain, by my calculations. (This might overstate Japan’s performance because many of its elderly still work.) As any visitor can attest, Japan remains a prosperous, harmonious and well-ordered place.

“Had you appointed me governor of the Bank of Japan for 25 years with all the power in the world, I don’t think I would have been able to do better,” said Fernández-Villaverde.

This doesn’t prove deflation was benign. Growth (and deflation) might have been worse without the BOJ’s herculean monetary efforts. And if inflation had been positive, growth might have been stronger.

Still, it raises an awkward question: If zero to negative inflation is so damaging, where is the evidence?

The price mechanism

The harm might lie in subtle behavioural changes by investors, companies and the public. For example, in a market economy, changing relative prices and wages are critical signals for reallocating capital and labor from stagnant to growing sectors.

Relative prices changes are unusually rare in Japan, according to the University of Tokyo economist Tsutomu Watanabe. He has found that from 1995 through 2021, prices of more than half of products didn’t change at all from year to year. This wasn’t just because average inflation was lower; price changes deviated from the average much less than in other countries.

In a December speech, Bank of Japan Governor Kazuo Ueda said years of low to negative inflation led to a “status quo in wage- and price-setting behaviour,” so many prices and wages didn’t change. “The know-how for raising prices was thus lost,” he said.

The absence of this price-discovery function, Ueda contended, sapped productivity and dynamism.

Watanabe’s research shows that since January 2022, prices have been less sticky and more dispersed. Coincidentally, the Nikkei’s latest rally began a year later.

This in great part reflects the enthusiasm of foreign investors such as Warren Buffett , shareholder-friendly changes in corporate governance, and Japan’s importance as an alternative to China for high-end manufacturing and technology.

Inflation, though, might also be a factor, said Paul Sheard , a former vice chairman at S&P Global who has studied the Japanese economy for decades. He added that investors care about nominal, not real, stock prices, earnings, dividends and cash flow.

Higher inflation flatters all those metrics. That benefit might be neutralised by higher interest rates, but Japanese bond yields have risen less than expected inflation, so real yields are down to minus 0.6%.

So perhaps inflation is reviving businesses’ and investors’ animal spirits. Even so, growth last year was about the same as before the pandemic and turned slightly negative in the third and fourth quarters, producing a technical recession . What’s more, wages have lagged behind inflation, and Prime Minister Fumio Kishida ’s approval ratings have plummeted.

Japan might have prevailed in its war against deflation. But ordinary Japanese have yet to see a peace dividend.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.