Searching for Solutions to the Decline in Philanthropy

The need for more philanthropy and the importance of volunteering was front and centre of a panel presented by Penta and United Way Worldwide at the Midnight Theatre in Manhattan on Thursday.

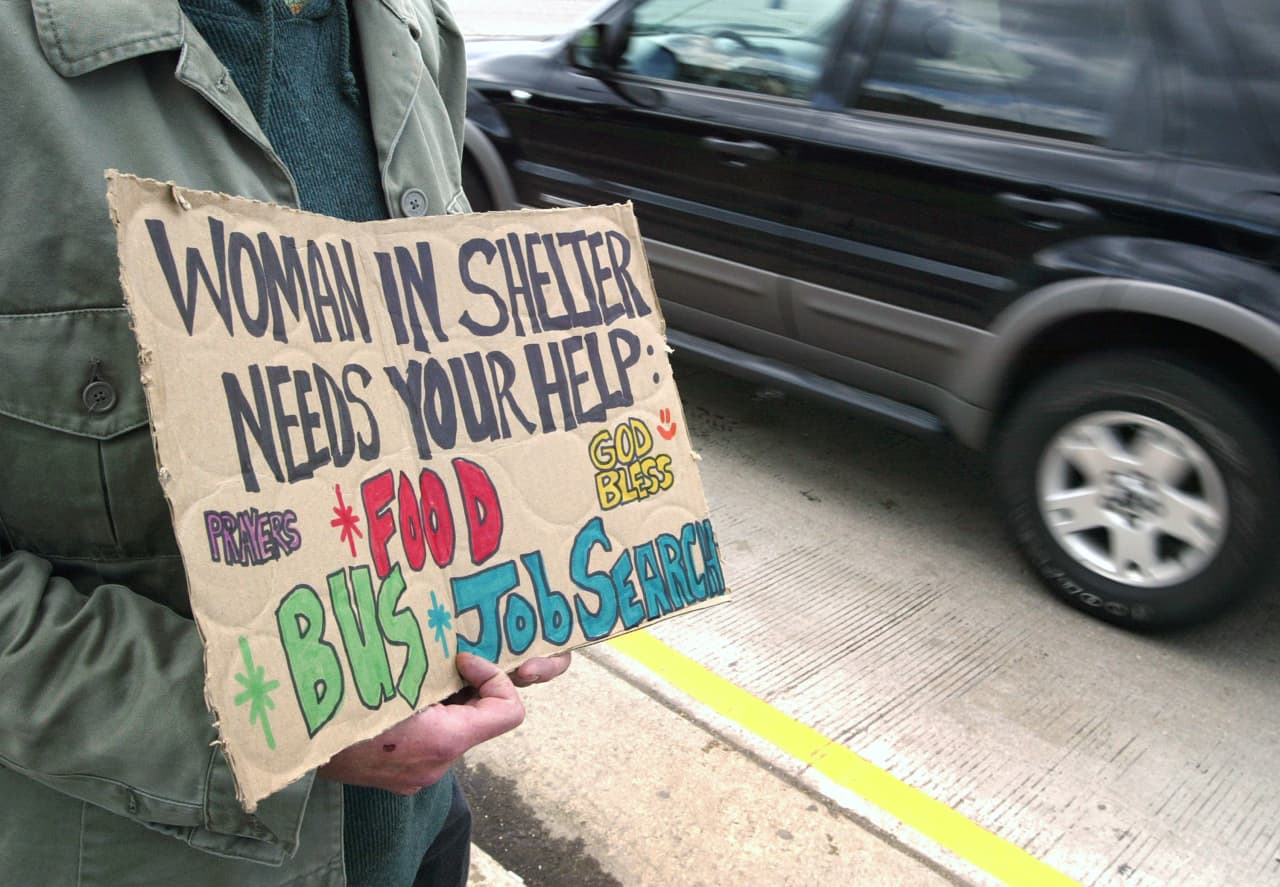

Half of working New Yorkers are struggling to make ends meet, according to a report released in April this year.

“The way we tackle that is through bringing partners together, from the corporate side, non-profits, and policy makers, to make sure that we are attacking the root causes,” said Grace C. Bonilla, CEO and president of United Way New York City.

Yet, philanthropy has been “decreasing” according to Angela F. Williams, CEO and president of United Way Worldwide (UWW), the 135-year-old non-profit which connects partners, donors, and volunteers in 1,100 communities across 37 countries.

Williams attributed the decline to several factors.

First, donations via once robust community institutions such as the church and popular charity schemes such as the United Way payroll deduction—formerly a staple in corporate culture—are not “as strong as [they] used to be.”

Second, young people want to see “immediate impact” when they donate a dollar and nonprofits are under increasing scrutiny over spending.’

“There is this missing understanding that some problems, some issues, whether it’s solving poverty, whether it’s graduation rates, whether it’s low-income housing, all of those things take time and have to be intentional,” said Williams in a discussion with Raymond J. McGuire, the president of financial advisory and asset management firm Lazard and 2021 candidate for New York City mayor.

Non-profit, she added, “doesn’t mean no profit, no margin. We have to operate; we have administrative costs.”

Williams said that there needs to be more emphasis on public-private partnership.

“We know that government can’t do it all, government can’t solve all the problems that are going on in communities and we also know that companies have employees in communities, and they draw their employees from those communities,” Williams said. “What company wants to operate in a community that is unhealthy, uneducated?”

“I think we need to do better,” McGuire agreed. “The challenges that we are now facing are as formidable if not more formidable than the challenges we have ever faced in their country…So we need to step up, we need to be more engaged.”

Last year, US$499 billion was raised in the U.S., according to Giving USA. US$319 billion came from individuals, US$105 billion from foundations, and US$45 billion from gifts in a will or trust. In comparison, just US$21 billion was from corporations.

“I can’t say it’s a responsibility, it’s an opportunity,” McGuire said. “My observations will be that the private sector will be even more involved and more engaged, because they recognise that there’s more at risk.”

For Ohio-native McGuire, whose mother was a social worker and whose grandfather only had a third-grade education and taught himself to read by perusing the Bible, the need to fight for a more equal society is personal. In 1979 he graduated from Harvard before becoming one of Wall Street’s longest-serving and most-successful Black executives.

“I had to make it in a world that was completely foreign for me and for people who look like me,” McGuire said. “The fundamental premise of that which we are attempting to attain is prosperity for all, at least the ability to participate. If there’s an opportunity for us to make a difference… then by definition the foundation of that which we stand for [has] got to be education.”

The Nation’s Report Card showed across the board declines in math and reading ability in 2022, declines that have particularly hit kids of colour, according to McGuire. “Before Covid, we weren’t making progress and now after Covid, post Covid we’ve retreated,” he said.

For Williams, who is the first Black woman to lead UWW, a salient solution is to create “a new table” of opportunity.

“I want a table that is inclusive, I want a table that brings in the voices of those who we are trying to solve for,” she said. “I want to have a table that says I’m not your saviour but I’m your partner, so come in and let’s talk… and co create.”

Williams used the example of United Way’s work in Maui, Hawaii, following the devastating summer wildfires.

“How do we make sure that the natives… can sit in the room and along with the state and federal government and county and city as well to say: How do we not lose our ancestral heritage?” she said. “How do we create a new thing and a new way of living and surviving and thriving that is equitable?”

Priorities for 2024 touched on in the panel included the climate, AI, energy transition, America’s ageing population, and cyber security.

The panel ended on a note of hope. Former NFL player Carl Nassib, who launched the app Rayze last year to connect people to non-profits, pointed out from his seat in the audience that roughly a quarter of Americans volunteer but 75% of those who do volunteer end up donating.

“Have you thought about the positive mental health benefits of volunteering and what they can do for young philanthropists?” he asked, suggesting that the recent mental health youth crisis is linked in part to a reduction in volunteering.

Volunteerism is “one of the ways that allow people to really become proximate to their community and to the issues they care about,” Williams pointed out earlier in the evening.

“And I think once you’re proximate and you get to walk alongside someone and you can see how you can relate and help them, that really makes the difference. And that it makes for a civil society, it makes for a civil human being.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Continued stagflation and cost of living pressures are causing couples to think twice about starting a family, new data has revealed, with long term impacts expected

Australia is in the midst of a ‘baby recession’ with preliminary estimates showing the number of births in 2023 fell by more than four percent to the lowest level since 2006, according to KPMG. The consultancy firm says this reflects the impact of cost-of-living pressures on the feasibility of younger Australians starting a family.

KPMG estimates that 289,100 babies were born in 2023. This compares to 300,684 babies in 2022 and 309,996 in 2021, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley said weak economic growth often leads to a reduced number of births. In 2023, ABS data shows gross domestic product (GDP) fell to 1.5 percent. Despite the population growing by 2.5 percent in 2023, GDP on a per capita basis went into negative territory, down one percent over the 12 months.

“Birth rates provide insight into long-term population growth as well as the current confidence of Australian families,” said Mr Rawnsley. “We haven’t seen such a sharp drop in births in Australia since the period of economic stagflation in the 1970s, which coincided with the initial widespread adoption of the contraceptive pill.”

Mr Rawnsley said many Australian couples delayed starting a family while the pandemic played out in 2020. The number of births fell from 305,832 in 2019 to 294,369 in 2020. Then in 2021, strong employment and vast amounts of stimulus money, along with high household savings due to lockdowns, gave couples better financial means to have a baby. This led to a rebound in births.

However, the re-opening of the global economy in 2022 led to soaring inflation. By the start of 2023, the Australian consumer price index (CPI) had risen to its highest level since 1990 at 7.8 percent per annum. By that stage, the Reserve Bank had already commenced an aggressive rate-hiking strategy to fight inflation and had raised the cash rate every month between May and December 2022.

Five more rate hikes during 2023 put further pressure on couples with mortgages and put the brakes on family formation. “This combination of the pandemic and rapid economic changes explains the spike and subsequent sharp decline in birth rates we have observed over the past four years,” Mr Rawnsley said.

The impact of high costs of living on couples’ decision to have a baby is highlighted in births data for the capital cities. KPMG estimates there were 60,860 births in Sydney in 2023, down 8.6 percent from 2019. There were 56,270 births in Melbourne, down 7.3 percent. In Perth, there were 25,020 births, down 6 percent, while in Brisbane there were 30,250 births, down 4.3 percent. Canberra was the only capital city where there was no fall in the number of births in 2023 compared to 2019.

“CPI growth in Canberra has been slightly subdued compared to that in other major cities, and the economic outlook has remained strong,” Mr Rawnsley said. “This means families have not been hurting as much as those in other capital cities, and in turn, we’ve seen a stabilisation of births in the ACT.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.