The Retreat of the Amateur Investors

A pandemic boom attracted scores of Americans seeking gains. Now that some are backing away, the markets risk losing a key support.

Amateur trader Omar Ghias says he amassed roughly $1.5 million as stocks surged during the early part of the pandemic, gripped by a speculative fervour that cascaded across all markets.

As his gains swelled, so did his spending on everything from sports betting and bars to luxury cars. He says he also borrowed heavily to amplify his positions.

When the party ended, his fortune evaporated thanks to some wrong-way bets and his excessive spending. To support himself, he says he now works at a deli in Las Vegas that pays him roughly $14 an hour plus tips and sells area timeshares. He says he no longer has any money invested in the market.

“I’m starting from zero,” said Mr. Ghias, who is 25.

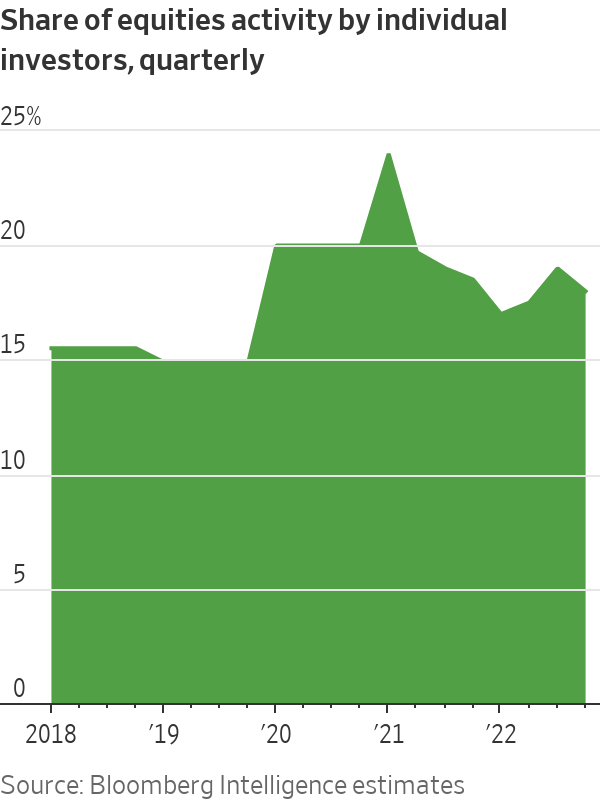

During the pandemic lockdowns in 2020 and 2021, scores of Americans got hooked on trading stocks, options and cryptocurrencies, driving up shares of companies that were once left for dead. Now some of these so-called retail investors are backing away from the markets after the worst year for stocks since 2008. Others are paring their positions or shifting their money to more conservative holdings, such as bonds or cash.

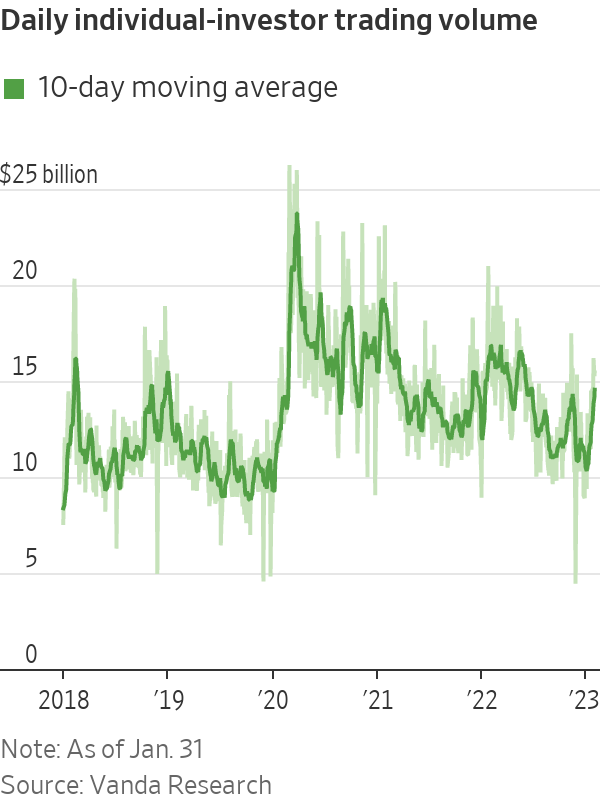

Last month, trading activity among retail investors as measured by dollar volumes hit its lowest level since January 2020, according to an analysis of some platforms by research firm Vanda Research. These investors are also trading less with brokerages that stoked their enthusiasm earlier in the pandemic, according to earnings reports. Households are expected to yank roughly $100 billion from the market in 2023, according to Goldman Sachs Group Inc., which would be the first net outflows since 2018.

What these amateur investors decide to do next will have big implications for the direction of the market. They are still collectively the biggest holders of U.S. equities, according to Goldman Sachs, and any retreat from stocks could remove a steady source of support at a turbulent moment. Fears about inflation and a possible future recession continue to loom, and many big companies are bracing for economic turmoil. Central-bank officials have repeatedly said their work to cool the economy isn’t done.

A run-up last month in certain stocks such as online car seller Carvana Co. and retailer Bed Bath & Beyond Inc. led some professional investors to speculate that individual investors were behind the moves. The overall market pushed higher this past week after the Federal Reserve raised interest rates by a widely expected quarter percentage point; the S&P 500 is up 7.7% thus far in 2023 and the Nasdaq 15%.

The early 2023 rally is still a far cry from what happened two years ago. Stuck at home during the Covid-19 pandemic and flush with stimulus checks, newbie traders encouraged each other to pile into stocks as they banded together on online forums such as Reddit, Discord and Twitter. At times they tried to intensify losses among professional traders who had bet against some of their favourite companies. The frenzy resulted in eye-popping surges in shares of troubled firms such as GameStop Corp. and AMC Entertainment Holdings Inc. Momentum trumped coolheaded analysis of company fundamentals.

Some of these rookie traders made small fortunes in 2021. But many lost money the following year as U.S. stocks fell along with bonds and cryptocurrencies, and their enthusiasm for trading waned.

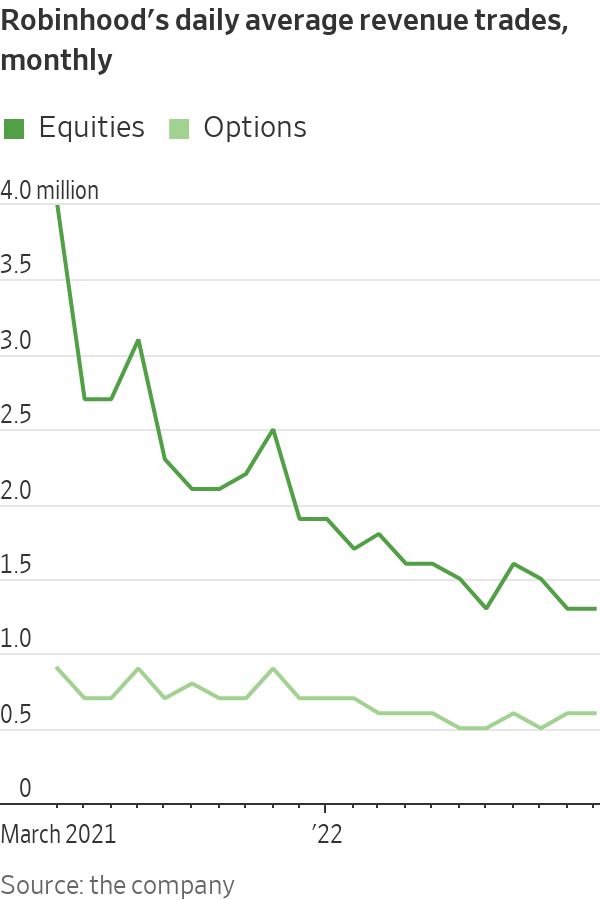

The average individual investor’s portfolio has declined 27% since peaking in December 2021, according to estimates from Vanda Research, compared with the S&P 500’s roughly 13% decline over the same period. Monthly active users at online brokerage app Robinhood Markets Inc., which helped make trading cool among newbies, recently fell to their lowest level since the company went public. At the more traditional brokerages of Morgan Stanley and Charles Schwab Corp., the average daily number of retail trades recently fell to the lowest levels since at least 2020.

Some retail investors are still active but more conservative with their bets. Sumit Gupta, a 49-year-old ophthalmologist in Charlotte, N.C., was among those who bought the dip in stocks in early 2022, when shares of everything from big tech stocks to broader S&P 500 dropped. He says he has been regularly adding to stockholdings over the past decade, using the dollar-cost averaging method.

The market kept falling. The S&P 500 notched its worst year since the 2008 financial crisis, stymied by a Federal Reserve forced to aggressively raise interest rates to cool red-hot inflation.

Since then, Mr. Gupta said, he realized how serious Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell was about raising interest rates and has shifted his strategy. He says he is putting extra cash into Treasurys. Yields on 10-year government bonds are hovering around 3.5%, up from less than 1% in 2020.

“Now there’s yield on cash again,” Mr. Gupta said. “At this stage in my career, I don’t need to be aggressive.”

Jonathan Javier, 28 years old, accelerated his trading during the pandemic, after mainly buying and holding investments for years.

Drawn in by the meteoric price increases in everything from cryptocurrencies to the S&P 500, he scooped up shares of technology stocks such as Meta Platforms Inc. and Apple Inc. He says he watched in awe as his portfolio roughly doubled through November 2021. Having worked at several big tech companies, he says he was confident they would keep growing, as they had for much of the past decade.

By mid-2022, the portfolio made a U-turn, falling about 8%. He says he slashed his regular investments by around half and backed away from the market. “I didn’t do much at all” last year, Mr. Javier said.

This year he says he bought some tech stocks once again, though he says he is much more wary of how much of his money he is comfortable risking. He says he is also not darting in and out of positions as much.

“Now I know the key to making a profit is buying when the stock is at a low price point instead of just buying and ‘hoping’ that I will make a gain from it.” Mr. Javier said.

Navroop Sandhu, a 32-year-old London web developer, was a newcomer who became enamored with trading during the early days of the pandemic as the value of a new account she created with online brokerage eToro skyrocketed. She would enter and exit positions within hours or hold for weeks, and actively participated in an online Discord trading group. She says she once asked her friends to bring their laptops with them to a restaurant in London, so she could dish out investing tips.

“It was like a snowball effect, where I just got addicted,” Ms. Sandhu said.

Now she says she is placing anywhere from two to five trades in a week, down from nearly 10 in some weeks in 2020. Ms. Sandhu says she is also trying to be patient in picking the right trading spots, which has helped her stay in the markets.

Some investors have exited the market. They include Mr. Ghias, the 25-year-old amateur trader who watched the value of his stock portfolio swing wildly during the early stages of the pandemic.

Mr. Ghias says his first exposure to investing happened as a teenager growing up in the suburbs of Chicago, where his guitar teacher would monitor stocks by phone. He and that guitar teacher say they would discuss everything from penny stocks to pot stocks to shares of larger companies. When he got to high school, he started trading with some of his own money in between jobs. He says he sometimes cut class in high school and college to trade.

Once the pandemic began, he gravitated to stocks and funds tracking the performance of metals as well as options, which allow investors to buy or sell shares at a certain price. He used these to generate income or profit from stock volatility. He also borrowed from his brokerage firms to amplify his positions, a tactic known as leverage.

In 2021, he started increasing that leverage, his brokerage statements show. He often turned to trades tied to the Invesco QQQ Trust, a popular fund tracking the tech-heavy Nasdaq-100 index, while continuing to bet heavily on metals. At times, he dabbled in options tied to hot stocks such as Tesla Inc. and Apple.

At one point, his leverage amounted to more than $1 million, brokerage statements reviewed by The Wall Street Journal show. By around June 2021, according to those brokerage statements, his portfolio was worth roughly $1.5 million.

“I really started treating the market like a casino,” Mr. Ghias said.

As his stock-market gains swelled, so did his spending and partying, he says. He says he started betting thousands on professional football games and enjoyed late nights at bars, racking up tabs drinking Don Julio 1942 tequila. Mr. Ghias and his former roommate Nick Palma say he spent thousands to see the Tampa Bay Buccaneers play, while betting roughly $35,000 that they would beat the Los Angeles Rams and go on to win the Super Bowl. They lost.

He and his former roommate say Mr. Ghias also footed the bill for friends to stay at a Las Vegas hotel and rented a black Lamborghini that he raced through the Strip. Some of his exploits, including the Lamborghini ride, he showed on a TikTok account that also featured footage of him trading in front of three computer screens. He says he stopped taking classes at DePaul University, in Chicago, so he could spend more time focused on the markets.

In late 2021, he placed one of his biggest bets. The Fed’s Mr. Powell had warned he was about to pull back the central bank’s easy-money policies, opening the door to tapering its monthly asset purchases. The plans threatened to inject a jolt of turbulence into a market that had been ascending to fresh records for much of the year.

Mr. Ghias says he thought the Fed was bluffing and made a speculative investment that he thought would benefit from an accommodative central bank, expecting prices of silver and gold to rally and help a portfolio that included a large position in Hecla Mining Co., statements show. He says he also added a bearish position tied to the Nasdaq.

The trade didn’t work, he says, and a broker demanded he post more money to fund his losses. By the end of the year, according to his statements, he had lost more than $300,000 in one account even as the S&P notched a gain of 27%.

“That was my breaking point,” Mr. Ghias said.

In 2022, he says he started taking even more risks trading options and betting on sports in hopes of making some of the money back. One big strategy was to gamble on the direction of the S&P 500 by buying and selling options contracts tied to that index that often expired the same day, brokerage statements show.

Mr. Ghias traded S&P 500 options at all hours, sometimes around midnight, placing some trades worth hundreds of thousands of dollars, brokerage statements show. For example, if he had a hunch that the S&P 500 would keep tumbling the next day, extending losses from its overnight session, he might sell options contracts that would profit from a steeper plunge. At times, he was left with losses from such trades, his statements show.

“That just put me in a really bad mental state,” Mr. Ghias said. “I began chasing losses.”

By the end of 2022, he had racked up bills of more than $300,000 on his American Express Platinum card, according to snapshots of his account viewed by the Journal, and he says the nest egg that had climbed to around $1.5 million was gone. “I lost it all,” Mr. Ghias said.

He decided to move to Las Vegas and began to work at an Italian deli and restaurant on the outskirts of town. He says he has also picked up short-term gigs and started selling timeshares. He is going on other job interviews, too, while documenting his new life on TikTok under the alias “OGTraderTV.” When one of his TikTok followers learned about his cash crunch, Mr. Ghias says he was offered a free stay at the Bellagio Hotel & Casino.

He says he has no money in the market right now and shared screenshots of his accounts showing that he has roughly $15,000 in credit card debt, around $36,000 in an auto loan and $6.99 in a checking account. He says he has some cash, too.

“I felt like I was indestructible,” Mr. Ghias said of his trading days. “It was irrational.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Says U.S. and China, which will continue to see a surge in borrowing if current policies remain in place.

The U.S. and Chinese governments should take action to lower future borrowing, as a surge in their debts threatens to have “profound” effects on the global economy and the interest rates paid by other countries, the International Monetary Fund said Wednesday.

In its twice-yearly report on government borrowing, the Fund said many rich countries have adopted measures that will lead to a reduction in their debts relative to the size of their economies, although not to the levels seen before the Covid-19 pandemic.

However, that is not true of the U.S. and China, which will continue to see a surge in borrowing if current policies remain in place. The Fund projected that U.S. government debt relative to economic output will rise by 70% by 2053, while Chinese debt will more than double by the same year.

The Fund said both countries will lead a rise in global government debt to 98.8% of economic output in 2029 from 93.2% in 2023. The U.K. and Italy are among the other big contributors to that increase.

“The increase will be led by some large economies, for example, China, Italy, the United Kingdom, and the United States, which critically need to take policy action to address fundamental imbalances between spending and revenues,” the IMF said.

The IMF expects U.S. government debt to be 133.9% of annual gross domestic product in 2029, up from 122.1% in 2023. And it expects China’s debt to rise to 110.1% of GDP by the same year from 83.6%.

The Fund said there had been “large fiscal slippages” in the U.S. during 2023, with government spending exceeding revenues by 8.8% of GDP, up from 4.1% in the previous year. It expects the budget deficit to exceed 6% over the medium term.

That level of borrowing is slowing progress toward reducing inflation, the Fund said, and may also increase the interest rates paid by other governments.

“Loose US fiscal policy could make the last mile of disinflation harder to achieve while exacerbating the debt burden,” the Fund said. “Further, global interest rate spillovers could contribute to tighter financial conditions, increasing risks elsewhere.”

A series of weak auctions for U.S. Treasurys are stoking investors’ concerns that markets will struggle to absorb an incoming rush of government debt. The government is poised to sell another $386 billion or so of bonds in May—an onslaught that Wall Street expects to continue no matter who wins November’s presidential election.

While analysts don’t expect those sales to fail, a sharp rise in U.S. bond yields would likely have consequences for borrowers around the world. The IMF estimated that a rise of one percentage point in U.S. yields leads to a matching rise for developing economies and an increase of 90 basis points in other rich countries.

“Long-term government bond yields in the United States remain elevated and sensitive to inflation developments and monetary policy decisions,” the Fund said. “This could lead to volatile financing conditions in other economies.”

China’s budget deficit fell to 7.1% of GDP in 2023 from 7.5% the previous year, but the IMF projects a steady pickup from this year to 7.9% in 2029. It warned that a slowdown in the world’s second largest economy “exacerbated by unintended fiscal tightening” would likely weaken growth elsewhere, and reduce aid flows that have become a significant source of funding for governments in Africa and Latin America.

An unusually large number of elections is likely to push government borrowing higher this year, the Fund said. It estimates that 88 economies or economic areas are set for significant votes, and that budget deficits tend to be 0.3% of GDP higher in election years than in other years.

“What makes this year different is not only the confluence of elections, but the fact that they will happen amid higher demand for public spending,” the Fund said. “The bias toward higher spending is shared across the political spectrum, indicating substantial challenges in gathering support for consolidation in the years ahead, and particularly in a key election year like 2024.”

Consumers are going to gravitate toward applications powered by the buzzy new technology, analyst Michael Wolf predicts

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.