Rich Countries Are Becoming Addicted to Cheap Labour

Businesses are relying more on migrant workers as labor shortages persist, but economists warn of long-term dangers

As migration hits record levels worldwide, a debate is building among economists over whether some industries are becoming too dependent on foreign labor.

Many business owners say that bringing in low-skilled foreign workers has become essential, as local populations age and labor forces shrink. In rural Wisconsin, John Rosenow says it is impossible to find locals to work on his 1,000-acre dairy farm. He relies on 13 Mexican immigrants, up from eight to 10 a decade ago. That has enabled him to avoid making costly investments in robots that can help milk cows, as some other dairy farmers have.

“We get really good people,” Rosenow says. With immigrant labor, “I’m pretty sure if I wanted to double employment, I could get it done within a week.”

To some economists, however, dependence on imported workers is approaching unhealthy levels in some places, stifling productivity growth and helping businesses delay the search for more sustainable solutions to labour shortages.

Those solutions could include bigger investments in automation, or more radical restructurings such as business closures, which are painful but may be necessary long-term, these economists say.

“Once industry is organised in a certain way and the structure encourages employers to recruit migrants, it can be very hard to turn back,” said Martin Ruhs , a professor of migration studies in Florence, Italy. “In some cases, policymakers should ask, does it make sense?” said Ruhs, who is also a former member of the U.K. Migration Advisory Committee, which advises the British government on migration policy.

The debate is likely to heat up further as Western societies teeter closer to a demographic abyss . For the first time since World War II, the working-age population is shrinking across advanced economies. The European Union’s working-age population will shrink by one-fifth through 2050, according to a recent report by German insurer Allianz .

There are ways to offset that trend, such as encouraging older workers to delay retirement. But importing foreign labor is often the easiest option, given the supply of available workers in places such as Latin America or Africa.

Immigration also provides a rush of economic growth as migrants boost populations and spend money, even when it elicits blowback from conservative groups, as it has in the U.S. and Europe.

Immigration is now running two to three times above pre pandemic levels across major destination countries including Canada, Germany and the U.K. In the U.S., 3.3 million more migrants arrived than left last year, compared with a 2010s average of around 900,000.

Three-quarters of farmworkers and 30% of construction and mining workers in the U.S. today are migrants. Overall, immigrants made up 18% of the U.S. workforce in 2021, compared with 16% a decade earlier, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, a Paris-based club of mostly rich countries.

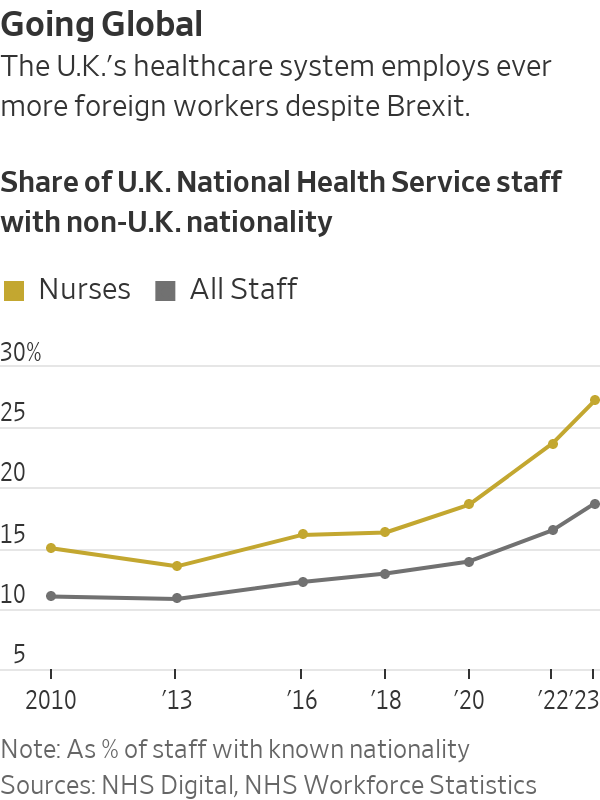

Despite promising for decades to curb immigration, the U.K. has seen a surge since its 2020 exit from the EU, as businesses scramble for employees. More than 27% of the National Health Service’s nurses are from abroad today, up from around 14% in 2013. In Germany, roughly 80% of slaughterhouse workers are migrants, unions estimate.

Downsides of over reliance

Increased reliance on low-skilled imported labor can lead to weaker productivity growth, which ultimately determines how fast economies can expand, some economic research suggests.

A 2022 study in Denmark found that firms with easy access to migrant workers invested less in robots. Research in Australia and Canada suggests that migrants could keep weak firms alive, weighing on overall productivity.

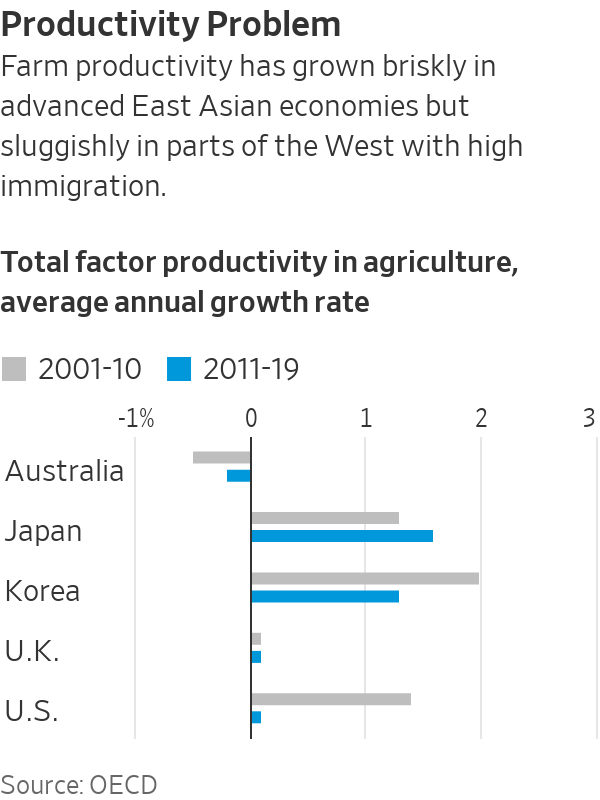

Labour productivity growth has been sluggish across advanced economies in recent years. In the U.S. and U.K. farming sectors, productivity has flatlined for a decade or longer. In Japan and Korea, which have more restrictive immigration policies, it increased by around 1.5% a year, OECD data show.

Finding the right balance between allowing some migration, which can help restore dynamism in ageing countries, and avoiding over dependence is hard. In many industries, there is no obvious alternative to foreign workers.

Going cold turkey would send prices for products made from migrant labour higher. It would also leave many people in poorer countries with fewer options to pursue better lives.

Anna Boucher , a global migration expert at the University of Sydney, says that some low-skilled migration is probably necessary in the short term due to skills shortages. Without it, some childcare services in Australia would shut down and vegetables would die in the fields.

Economic research suggests that an influx of high-skilled migrants, such as scientists and engineers, can actually lift firms’ productivity and boost local workers’ wages and employment opportunities.

Economists are more divided when it comes to lower-skilled migrants. Such workers are also more easily replaced, including in industries that seem unlikely candidates for automation.

In the Czech Republic, some farmers are using artificial-intelligence-driven robots to monitor and harvest strawberries. Israeli startup Tevel Aerobotics Technologies has developed fruit-picking drones. Fieldwork Robotics, a U.K. company, recently started selling raspberry-picking robots, which stand 6 feet tall with four plastic arms.

Yet for governments, pursuing reforms that boost productivity and allow weaker firms to die is a lot harder than increasing immigration, said Dan Andrews , a productivity expert at the OECD.

“Some countries may have taken the easy way out,” he said.

Pushback from businesses

Hoping to accelerate automation in agriculture, the U.K. government is pouring money into farm technology. It is also considering abolishing rules that allow companies to pay migrant workers 20% less than the going rate for jobs, prompting protests from farmers’ lobby groups. They say farmers adopt technology quickly if it is available, but that robots are no good at picking fruit and vegetables.

“The technology that we are aiming for is five years away…we were saying that five years ago,” said Martin Emmett , a farmer and official at the National Farmers’ Union, a trade group.

In Malaysia, the government last year announced a freeze on hiring of new foreign workers. Government ministers say that over dependence on cheap foreign labor has created a detrimental cycle that allows companies to resist innovation. Local companies say they need more time to invest in automation and upgrade workers’ skills.

Some industries, including manufacturing and plantations, have since been allowed to hire foreigners following appeals, but the broader freeze on foreign workers remains in place with no end date.

In Canada, economists say the government has cast aside a carefully managed immigration system that gave priority to highly skilled workers, and ramped up significantly the intake of foreign students and other low-skilled temporary workers. By flooding the market with cheap labor, Ottawa may be propping up uncompetitive businesses and ultimately damaging productivity, according to a December report co-written by former Canadian central-bank governor David Dodge .

Economic output per capita is lower than it was in 2018 following years of record immigration, notes Mikal Skuterud , an economist at Waterloo University in Ontario. Canada has been bringing in so many low-skilled workers that it lowers the country’s productivity overall, he says.

Germany’s butcher conundrum

The debates are also intensifying in Germany, where businesses including butcher shops in the foothills of the Black Forest are becoming more reliant on imported labor.

Young people don’t want to train as butchers anymore, local businesses say, because it is unglamorous work, with low pay. Labour shortages are one reason why the number of butcher shops has roughly halved over the past two decades.

Three years ago, Handirk von Ungern-Sternberg , an official at the local chamber of handicrafts, started a pilot project to recruit butchers’ apprentices in India, taking advantage of a change in German law that made it easier to hire low-skilled workers from outside the EU. The first batch of 13 young Indians arrived in September 2022.

Now, demand is exploding. Von Ungern-Sternberg plans to bring in roughly 140 Indian workers this year. That number could triple in future, he says.

From auto mechanics to construction, local businesses are clamouring for his young Indian recruits. Chambers of handicrafts across Germany, from the Alps to the North Sea, are seeking his help in starting similar projects.

“We ask ourselves, where’s the limit? Are we a job company? We don’t know where the ceiling is,” von Ungern-Sternberg said.

The program also benefits consumers by helping keep butchers’ costs low. Across the border in Switzerland, where Indian workers aren’t available, meat costs nearly four times as much.

However, Swiss business owners have also been experimenting with new technologies, including sausage vending machines known as Wurstautomaten, which could reduce the need for small-scale butcher’s shops and ultimately help bring prices down.

Meanwhile, opposition to immigration is rising in Germany, which suggests the butchers’ reliance on imported labor might not be sustainable. Support for the anti-immigrant Alternative for Germany party recently hit an all-time high of 23%. Polls suggest it could emerge as the strongest political force in several German state elections later this year.

Dairy dilemma

In Wisconsin, Rosenow, the dairy farmer, says he’s skeptical of the automated milking machines that he says are advertised in farm magazines. Some neighbours experimented with robots but went back to human labor because the robots constantly needed repairs, he says.

Robots would also cost twice as much as immigrant workers and be costly to maintain, Rosenow says. With immigrants, “labor is no constraint.”

Onan Whitcomb , a dairy farmer in Vermont, disagrees. He says that when he wanted to increase production he decided not to hire immigrant workers. Instead, he spent $800,000 on four Dutch-made milking robots.

Milk production per cow has grown by 30% and the incidence of mastitis, an inflammatory disease, has declined by 80%, he says, meaning less spent on antibiotics. Whitcomb says he was able to cut 2.5 jobs, and the investment paid for itself in seven years.

“We were milking 300 cows and we went to 240, and we still made more” milk, Whitcomb said. “That’s hard to beat.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

A resurgence in high-end travel to Egypt is being driven by museum openings, private river journeys and renewed long-term investment along the Nile.

In the lead-up to the country’s biggest dog show, a third-generation handler prepares a gaggle of premier canines vying for the top prize.

Parts for iPhones to cost more owing to surging demand from AI companies.

Apple has dominated the electronics supply chain for years. No more.

Artificial-intelligence companies are writing huge checks for chips, memory, specialised glass fibre and more, and they have begun to out-duel Apple in the race to secure components.

Suppliers accustomed to catering to Apple’s every whim are gaining the leverage to demand that the iPhone maker pay more.

Apple’s normally generous profit margins will face pressure this year, analysts say, and consumers could eventually feel the hit.

Chief Executive Tim Cook mentioned the problem in a Thursday earnings call, saying Apple was seeing constraints in its chip supplies and that memory prices were increasing significantly.

Those comments appeared to weigh on Apple shares, which traded flat despite blowout iPhone sales and record company profit.

“Apple is getting squeezed for sure,” said Sravan Kundojjala, who analyses the industry for research firm SemiAnalysis.

AI chip leader Nvidia recently became the largest customer of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing , or TSMC, Nvidia Chief Executive Jensen Huang said on a podcast.

Apple had been TSMC’s biggest customer by a wide margin for years. TSMC is the world’s leading manufacturer of advanced chips for AI servers, smartphones and other computing devices.

Spokesmen for Apple and TSMC declined to comment.

The big computers that handle AI tasks don’t look like the smartphones consumers own, but many companies supply components for both. In particular, memory chips are in short supply as companies such as OpenAI, Alphabet’s Google, Meta , Microsoft and others collectively spend hundreds of billions of dollars to build AI computing capacity.

“The rate of increase in the price of memory is unprecedented,” said Mike Howard , an analyst for research firm TechInsights.

That applies both to the flash memory chips that store photos and videos, called NAND, as well as the memory used to run apps quickly, called DRAM.

By the end of this year, the price of DRAM will quadruple from 2023 levels, and NAND will more than triple, estimates TechInsights.

Howard estimates that Apple could pay $57 more for the two types of memory that go into the base-model iPhone 18 due this fall compared with the base model iPhone 17 currently on sale. For a device that retails for $799, that would be a big hit to profit margins.

Apple’s purchasing power and expertise in designing advanced electronics long made it an unrivaled Goliath among the Asian companies that make most of the iPhone’s parts and assemble the device.

Apple spends billions of dollars a year on NAND, for instance, according to people familiar with the figures, likely making it the single biggest buyer globally. Suppliers flocked to win Apple’s business, hoping to leverage its know-how and prestige to attract other customers.

These days, however, “the companies now pushing the boundaries of human‑scale engineering are the ones like Nvidia,” said Ming-chi Kuo, an analyst with TF International Securities.

Demand for AI hardware is poised to keep growing rapidly. Apple’s spending growth is modest in comparison with what is being spent to fill up AI data centers, even though it is breaking records with huge sales of the iPhone 17.

Samsung Electronics and SK Hynix are raising the price of a type of DRAM chip for Apple, according to people familiar with Apple’s supply chain.

Big AI companies pay generously and are willing to lock in supply and make upfront payments, giving the South Korean chip makers leverage against the iPhone maker.

Apple signs long-term contracts for memory, but it has used its heft to squeeze suppliers.

Its contracts have empowered it to negotiate prices as often as weekly, and to even refuse to buy any memory from a supplier if Apple didn’t view the price as favorable, according to people familiar with its memory purchases.

To boost leverage with suppliers, Apple even began stocking more inventory of memory. That was atypical for Cook, who normally cuts inventory to the bone to maximize Apple’s cash flow.

Apple is fighting not only for current deliveries but also for the attention of engineers at suppliers.

Glass scientists who worked on developing the smoothest and lightest smartphone displays are now also spending time on specialised glass for packaging advanced AI processing chips, according to industry executives.

Makers of sensors and other gizmos inside the iPhone are winning new business from AI companies such as OpenAI that are developing their own hardware.

Still, suppliers said they were far from giving up on business with Apple. Working with Apple is a form of education, they said, because it remains one of the most demanding and disciplined customers in the industry.

TSMC, the Taiwanese chip manufacturer, has built successive generations of its most advanced chips with Apple as its lead customer, relying on the big predictable demand for iPhones.

Now that TSMC is doing more business with Nvidia and other AI companies, people with knowledge of the chip supply chain said Apple was exploring whether some lower-end processors could be made by someone other than TSMC.

One of Apple’s biggest profit-spinners is selling extra memory for far more than the memory chips cost the company.

Last fall Apple discontinued the iPhone Pro model with 128 gigabytes of storage.

Customers who want that model must now start at 256 gigabytes and pay $100 more—the type of move that could be repeated this year to help Apple offset higher costs, wrote Craig Moffett, an analyst at Moffett Nathanson, in an investor note.

However, Apple isn’t expected to raise the price of its next iPhone models over similarly equipped iPhone 17s, said Kuo, the analyst.

News Corp, owner of The Wall Street Journal, has a commercial agreement to supply news through Apple services.

A long-standing cultural cruise and a new expedition-style offering will soon operate side by side in French Polynesia.

The sports-car maker delivered 279,449 cars last year, down from 310,718 in 2024.