Australian property price falls may have already peaked

Hoping for further property price falls? Don’t hold your breath.

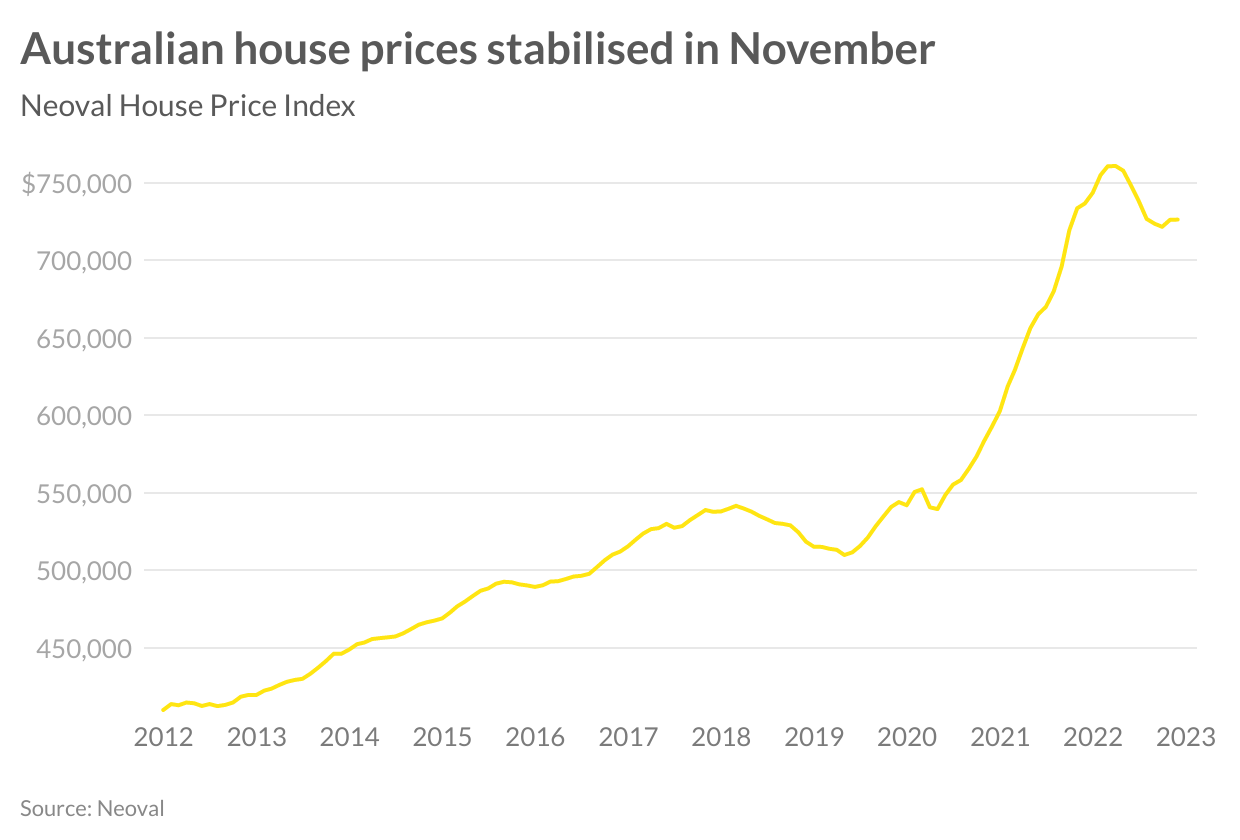

Rapid interest rate rises might have taken a toll on property prices, which reached an all-time high last year but the greatest drops may have already happened, Ray White economist Nerida Conisbee said today.

In a country as large and varied as Australia, positions for borrowers have ranged from low debt and high income conditions in some mining regions to high debt and high interest rates in cities like Sydney, where prices have fallen by more than 10 percent in the past year.

Low unemployment and accelerated population growth are also putting greater pressure on housing demand, keeping prices steady, she said.

“Although many people are starting to feel the pinch with increasing interest rates, as well as high inflation, we are yet to see this flow through to distressed sales,” Ms Conisbee said. “Prior to the interest rate rises, borrowers were assessed on being able to pay three percent over their mortgage rate.

“We have now hit that three percent rise but banks are profitable and well capitalised. As a result they are in a good position to assist people who are struggling with high debt levels.”

Some sellers are also sitting back, with more buyers competing for those properties on the market. Ms Conisbee said property sales are down more than 10 percent on last year.

While Australian property prices may have already taken their biggest tumble, Ms Conisbee said there may still be decreases on the cards.

“While inflation appears to be coming down, we may still see more interest rate increases next year if it fails to come down quickly enough,” she said. “Unemployment is very low but is expected to start to rise next year as the economy slows.

“The high levels of uncertainty are expected to continue into at least the first quarter of 2023.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

A Sydney site with a questionable past is reborn as a luxe residential environment ideal for indulging in dining out

Long-term Sydney residents always had handful of not-so-glamourous nicknames for the building on the corner of Cleveland and Baptist Streets straddling Redfern and Surry Hills, but after a modern rebirth that’s all changed.

Once known as “Murder Mall” or “Methadone Mall”, the 1960s-built Surry Hills Shopping Centre was a magnet for colourful characters and questionable behaviour. Today, however, a $500 million facelift of the site — alongside a slow and steady gentrification of the two neighbouring suburbs — the prime corner property has been transformed into a luxury apartment complex Surry Hills Village by developer Toga Group.

The crowning feature of the 122-apartment project is the three-bedroom penthouse, fully completed and just released to market with a $7.5 million price guide.

Measuring 211sqm of internal space, with a 136sqm terrace complete with landscaping, the penthouse is the brand new brainchild of Surry Hills local Adam Haddow, director of architecture at award-winning firm SJB.

Victoria Judge, senior associate and co-interior design lead at SJB says Surry Hills Village sets a new residential benchmark for the southern end of Surry Hills.

“The residential offering is well-appointed, confident, luxe and bohemian. Smart enough to know what makes good living, and cool enough to hold its own amongst design-centric Surry Hills.”

Allan Vidor, managing director of Toga Group, adds that the penthouse is the quintessential jewel in the crown of Surry Hills Village.

“Bringing together a distinct design that draws on the beauty and vibrancy of Sydney; grand spaces and the finest finishes across a significant footprint, located only a stone’s throw away from the exciting cultural hub of Crown St and Surry Hills.”

Created to maximise views of the city skyline and parkland, the top floor apartment has a practical layout including a wide private lobby leading to the main living room, a sleek kitchen featuring Pietra Verde marble and a concealed butler’s pantry Sub-Zero Wolf appliances, full-height Aspen elm joinery panels hiding storage throughout, flamed Saville stone flooring, a powder room, and two car spaces with a personal EV.

All three bedrooms have large wardrobes and ensuites with bathrooms fittings such as freestanding baths, artisan penny tiles, emerald marble surfaces and brushed-nickel accents.

Additional features of the entertainer’s home include leather-bound joinery doors opening to a full wet bar with Sub-Zero wine fridge and Sub-Zero Wolf barbecue.

The Surry Hills Village precinct will open in stages until autumn next year and once complete, Wunderlich Lane will be home to a collection of 25 restaurants and bars plus wellness and boutique retail. The EVE Hotel Sydney will open later in 2024, offering guests an immersive experience in the precinct’s art, culture, and culinary offerings.

The Surry Hills Village penthouse on Baptist is now finished and ready to move into with marketing through Toga Group and inquiries to 1800 554 556.

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.