Can Innovation Curb AI’s Hunger for Power?

Nvidia says its machine-learning chips have become 45,000 times more energy efficient, with further improvements in the pipeline

Artificial intelligence is known for its seemingly insatiable appetite for energy. But some tech leaders and analysts are questioning the extent of AI’s footprint going forward, saying innovations in the sector could help offset rising energy demand.

There is certainly no shortage of forecasts detailing the ominous rise in AI’s energy consumption. One commonly-cited report by Climate Action against Disinformation, an association of environmental groups, suggests that AI could drive up global emissions by 80%.

Another estimate by researcher Alex de Vries—which he described as a worst-case scenario—suggests that Google’s AI alone could eventually rack up as much annual electricity demand as the country of Ireland.

Such predictions present a substantial challenge for the relationship between computing and the climate in the coming years.

However, others see reason for optimism. In a Salesforce survey of about 500 corporate sustainability professionals, published Wednesday, nearly half were concerned about AI’s potential negative impacts on sustainability efforts. Meanwhile, almost 60% thought the benefits of AI would offset its risks in addressing the climate crisis.

Microsoft founder Bill Gates recently weighed in on the subject, urging governments not to go “overboard” on concerns about AI’s energy footprint, and suggesting that the technology could actually drive a reduction in global energy demands.

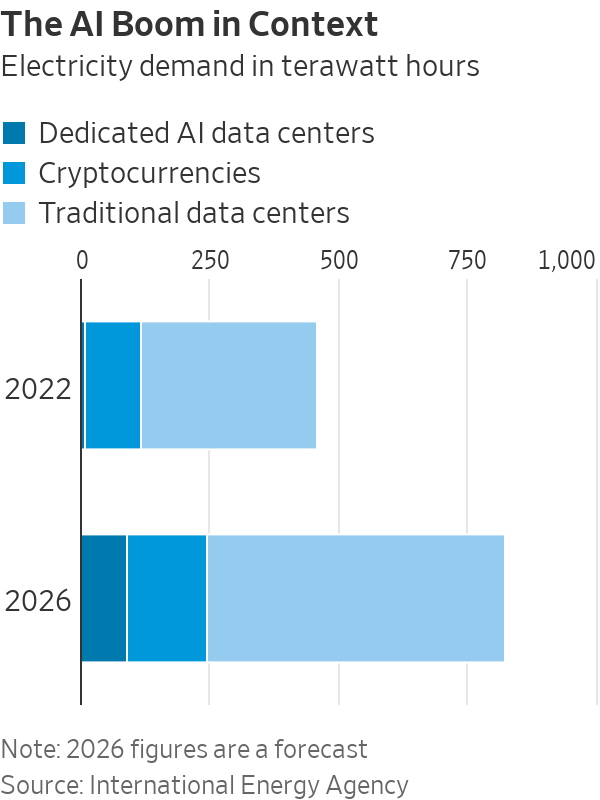

Putting the AI boom in context

The rise of AI should be considered in a broader perspective, according to Charles Boakye, U.S. sustainability analyst at Jefferies. He noted that relative to other industries, the technology still makes up only a fraction of global power demands.

“Data centers—the engines powering everything from AI to traditional computing to cryptocurrency—currently account for about 2% of global electricity consumption. Of this, AI accounts for roughly 0.5%,” Boakye said.

In terms of emissions, statistics last year from the International Energy Agency showed in total, data centers and transmission networks are responsible for 1% of energy-related greenhouse gases. For comparison, the oil-and-gas industry contributed just under 15% of emissions in 2022.

Looking ahead, the intergovernmental organisation said that by 2026, demand for AI is expected to increase ten fold compared with 2023. Even so, IEA data showed that it will still only account for roughly an eighth of total data-center electricity consumption.

“So in terms of AI demand, we’re talking about a small piece of a small piece,” Boakye said, noting that other areas of electrification, such as electric mobility, traditional data center growth and the industrial transition, will ask much greater questions of the power sector.

Charting efficiency trends

Demand is difficult to predict. But recent trends show that in practice, a rise in demand for computing power rarely correlates one for one with a rise in energy consumption, according to climate researcher Jonathan Koomey.

“Between 2010 and 2018, global data centres saw a 550% increase in compute instances and a 2,500% increase in storage capacity. This compares with just a 6% rise in electricity use,” he said.

Koomey, previously a visiting professor at Stanford, Yale and Berkeley, is best known for his work studying long-term trends in the energy-efficiency—now known as Koomey’s Law—highlighting the propensity of computing technologies to become more efficient over time.

AI may be a different animal, with some estimates suggesting large models such as ChatGPT use 10 times more energy than a Google search. But this is unsurprising for a relatively new technology, Koomey noted. In most areas of computing, energy demand tends to spike before levelling off as efficiencies gather pace, he said, noting that forecasts based on this inflection point will often be misguided.

Koomey cited a brief moment in the mid 1990s when internet data flows doubled every hundred days—a statistic that led to overinvestment in networks in the following years and 97% of fibre capacity sitting unused.

Similar efficiency trends can be seen in the development of AI, Jefferies analyst Boakye said. Google’s new TPU processors, for example, are more than 67% more efficient than in 2022, and the energy used to train OpenAI’s ChatGPT models has gone down by 350 times since 2016, he noted.

“It’s in their best interest, and in the interest of their business models, to increase that efficiency,” the analyst said.

Going for gold in the AI Olympics

If any company will have a say in the future of AI, it’s Nvidia . The U.S. technology company designs roughly 80% of the world’s specialized AI chips. Its next-generation GPUs, known as Blackwell, are touted to be 25 times more energy efficient than current iteration Hopper, while offering 30 times more computing power. Blackwell chips are slated for release later this year.

So far, the progress appears consistent, with Hopper 25 to 30 times more efficient than Nvidia’s previous generation of chips. Overall, the company said it has experienced a 45,000 times improvement in GPU energy efficiency over the last eight years.

Nvidia added that software optimisation also plays a big role in increasing the energy efficiency of its products.

“Once a platform has been launched, we will make it more efficient in a single year,” the company said. In the year following its launch in 2022, Hopper became two times more efficient after taking part in MLPerf, otherwise known as the Olympics of AI, in which tech companies compete and collaborate to drive improvements in the speed and efficiency of their models.

Part of this optimization involves taking large, energy-intensive AI models—such as ChatGPT—and refining them to perform more specific tasks. On July 18, for example, OpenAI launched a smaller, smarter and more energy efficient version of its previous GPT model, known as GPT-4o mini. Koomey sees these more “lightweight” models driving demand in the future .

“I’m not convinced large-scale AI has a good business model at this point, despite them driving all the investment. The slam dunk machine learning usually involves smaller, more efficient models, focused on a specific task. For me, this is where most of the business value lies,” he said.

Training and education will be essential for getting a more targeted and efficient experience with AI, helping to narrow the gap between businesses and their sustainability goals, said Suzanne DiBianca, Salesforce’s chief impact officer.

According to Nvidia, another way of alleviating AI’s impact is directing workloads—particularly the more energy-intensive jobs of training AI models—to regions with more abundant resources, ideally renewables which are set to keep a lid on electricity emissions in the coming years.

One company making strides in this space is NexGen Cloud, which builds renewable-powered data centers in areas with untapped energy resources.

According to co-founder and CSO Youlian Tzanev, a large portion of AI workloads don’t need to be performed close to traditional logistical hubs like London or New York, and can be powered from more remote areas in countries like Canada and Norway with excess hydropower.

“We have significantly more power than people believe. The power just isn’t reaching the grid in many cases and is going to waste, and so that is where we focus our efforts,” Tzanev said.

In the U.S., Crusoe Energy Systems offers another example of startups finding innovative ways to power the AI boom. Crusoe’s modular data centers are designed to run on excess natural gas produced at oil wells, achieving a 99.9% methane reduction in the process.

Common forecasting pitfalls

Projecting an outlook for AI’s energy demands is far from straightforward. In its midyear electricity update, the IEA noted that estimates exhibit a wide range of uncertainty, with some analyses following overly “simplistic” extrapolations.

For instance, the organization said certain studies make the mistake of assuming data center operators build all the facilities for which they apply to utilities. Given that several applications can be made for each new data center, this can lead to a multiplication of estimates.

Within data centers themselves, it is tempting for forecasters to imagine computers working flat out around the clock, Koomey said. In practice, GPUs usually operate on much less than their full power capacity, he added.

Based on modeling carried out by Nvidia, GPUs on average tend to run on less than 70% of their potential power. One particular function, known as Multi-Instance GPU, enables workloads—and therefore energy consumption—to be split into seven distinct components, with each able to function independently.

In addition, the company noted the role of substitution effects, in which traditional computing workloads are transferred onto AI platforms and subsequently performed more efficiently—an aspect that can be easily overlooked.

Forecasts can also conflate local data-centre developments with broader energy demands , Koomey added, noting that the most common estimates for electricity demand come from local utility companies.

In the U.S. as a whole, electricity use actually fell in 2023 compared with the previous year, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. In March 2024—the most recent month of available data—total demand reached 306 billion kilowatt-hours, down from 317 billion kWh in the year-prior period.

“I worry that people are jumping on the explosive demand-growth train before really understanding what’s going on,” Koomey said. “If you cluster data centers in certain places you’re going to see some local power constraints, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that AI will be a key driver of electricity use more broadly.”

Corrections & Amplifications undefined Nvidia said it has experienced a 45,000 times improvement in GPU energy efficiency over the last eight years. An earlier version of this article incorrectly said the company developed its first GPU eight years ago. (Corrected on July 24)

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

A divide has opened in the tech job market between those with artificial-intelligence skills and everyone else.

A 30-metre masterpiece unveiled in Monaco brings Lamborghini’s supercar drama to the high seas, powered by 7,600 horsepower and unmistakable Italian design.

A divide has opened in the tech job market between those with artificial-intelligence skills and everyone else.

There has rarely, if ever, been so much tech talent available in the job market. Yet many tech companies say good help is hard to find.

What gives?

U.S. colleges more than doubled the number of computer-science degrees awarded from 2013 to 2022, according to federal data. Then came round after round of layoffs at Google, Meta, Amazon, and others.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts businesses will employ 6% fewer computer programmers in 2034 than they did last year.

All of this should, in theory, mean there is an ample supply of eager, capable engineers ready for hire.

But in their feverish pursuit of artificial-intelligence supremacy, employers say there aren’t enough people with the most in-demand skills. The few perceived as AI savants can command multimillion-dollar pay packages. On a second tier of AI savvy, workers can rake in close to $1 million a year .

Landing a job is tough for most everyone else.

Frustrated job seekers contend businesses could expand the AI talent pipeline with a little imagination. The argument is companies should accept that relatively few people have AI-specific experience because the technology is so new. They ought to focus on identifying candidates with transferable skills and let those people learn on the job.

Often, though, companies seem to hold out for dream candidates with deep backgrounds in machine learning. Many AI-related roles go unfilled for weeks or months—or get taken off job boards only to be reposted soon after.

Playing a different game

It is difficult to define what makes an AI all-star, but I’m sorry to report that it’s probably not whatever you’re doing.

Maybe you’re learning how to work more efficiently with the aid of ChatGPT and its robotic brethren. Perhaps you’re taking one of those innumerable AI certificate courses.

You might as well be playing pickup basketball at your local YMCA in hopes of being signed by the Los Angeles Lakers. The AI minds that companies truly covet are almost as rare as professional athletes.

“We’re talking about hundreds of people in the world, at the most,” says Cristóbal Valenzuela, chief executive of Runway, which makes AI image and video tools.

He describes it like this: Picture an AI model as a machine with 1,000 dials. The goal is to train the machine to detect patterns and predict outcomes. To do this, you have to feed it reams of data and know which dials to adjust—and by how much.

The universe of people with the right touch is confined to those with uncanny intuition, genius-level smarts or the foresight (possibly luck) to go into AI many years ago, before it was all the rage.

As a venture-backed startup with about 120 employees, Runway doesn’t necessarily vie with Silicon Valley giants for the AI job market’s version of LeBron James. But when I spoke with Valenzuela recently, his company was advertising base salaries of up to $440,000 for an engineering manager and $490,000 for a director of machine learning.

A job listing like one of these might attract 2,000 applicants in a week, Valenzuela says, and there is a decent chance he won’t pick any of them. A lot of people who claim to be AI literate merely produce “workslop”—generic, low-quality material. He spends a lot of time reading academic journals and browsing GitHub portfolios, and recruiting people whose work impresses him.

In addition to an uncommon skill set, companies trying to win in the hypercompetitive AI arena are scouting for commitment bordering on fanaticism .

Daniel Park is seeking three new members for his nine-person startup. He says he will wait a year or longer if that’s what it takes to fill roles with advertised base salaries of up to $500,000.

He’s looking for “prodigies” willing to work seven days a week. Much of the team lives together in a six-bedroom house in San Francisco.

If this sounds like a lonely existence, Park’s team members may be able to solve their own problem. His company, Pickle, aims to develop personalised AI companions akin to Tony Stark’s Jarvis in “Iron Man.”

Overlooked

James Strawn wasn’t an AI early adopter, and the father of two teenagers doesn’t want to sacrifice his personal life for a job. He is beginning to wonder whether there is still a place for people like him in the tech sector.

He was laid off over the summer after 25 years at Adobe , where he was a senior software quality-assurance engineer. Strawn, 55, started as a contractor and recalls his hiring as a leap of faith by the company.

He had been an artist and graphic designer. The managers who interviewed him figured he could use that background to help make Illustrator and other Adobe software more user-friendly.

Looking for work now, he doesn’t see the same willingness by companies to take a chance on someone whose résumé isn’t a perfect match to the job description. He’s had one interview since his layoff.

“I always thought my years of experience at a high-profile company would at least be enough to get me interviews where I could explain how I could contribute,” says Strawn, who is taking foundational AI courses. “It’s just not like that.”

The trouble for people starting out in AI—whether recent grads or job switchers like Strawn—is that companies see them as a dime a dozen.

“There’s this AI arms race, and the fact of the matter is entry-level people aren’t going to help you win it,” says Matt Massucci, CEO of the tech recruiting firm Hirewell. “There’s this concept of the 10x engineer—the one engineer who can do the work of 10. That’s what companies are really leaning into and paying for.”

He adds that companies can automate some low-level engineering tasks, which frees up more money to throw at high-end talent.

It’s a dynamic that creates a few handsomely paid haves and a lot more have-nots.

Once a sleepy surf town, Noosa has become Australia’s prestige property hotspot, where multi-million dollar knockdowns, architectural showpieces and record-setting sales are the new normal.

When the Writers Festival was called off and the skies refused to clear, one weekend away turned into a rare lesson in slowing down, ice baths included.