The One-Child Policy Supercharged China’s Economic Miracle. Now It’s Paying the Price.

Revised U.N. data shows the speed of China’s aging after it accelerated its ‘demographic dividend’

When China launched its one-child policy more than four decades ago, it sped up an evolution toward smaller family sizes that would have happened more gradually.

The policy supercharged the country’s workforce: By caring for fewer children, young people could be more productive and put aside more money. For years, just as China was opening its economy, the share of working-age Chinese grew faster than the parts of the population that didn’t work. That was a big factor in China’s economic miracle.

There was a price and China is now paying it. Limiting births then means fewer workers now, and fewer women to give birth. A United Nations forecast published Thursday shows how quickly China is aging, a demographic crunch that the U.N. predicts will cut China’s population by more than half by the end of the century.

In the late 1970s, China’s leaders feared a population explosion that would drain the country’s resources. When Deng Xiaoping rolled out the one-child policy nationwide in 1980, he said, “We must do this. Otherwise, our economy cannot be developed well.”

A young population has helped drive economic growth in developing countries across the world, including in China’s neighbor Japan starting in the 1950s. Economists call it a demographic dividend—the window, generally of a few decades, when a country has far more working-age people than young and elderly dependents. As such countries grow wealthier, people naturally choose to have fewer children and the population starts to age.

That was also the trajectory in China—just faster.

Knowingly or not, China essentially borrowed from its own future by accelerating its so-called demographic window. How the effects of the policy have sped up China’s demographic bind is scrambling the long-term models demographers usually work with.

“The challenge with China is that from one year to another the situation can change quite fast,” said Patrick Gerland , head of the U.N.’s population estimates and projection section. “Within the last decade, the changes have been very big, both in policy and in the numbers.”

For example, in its just-published global estimates, the U.N. expects China’s population to drop from 1.4 billion today to 639 million by 2100, a much steeper drop than the 766.7 million it predicted just two years ago.

Even so, the U.N.’s prediction looks optimistic compared with other estimates. Researchers from Victoria University in Australia and the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences have predicted that China will have just 525 million people by the end of the century.

It is impossible to say what China’s population trajectory would have been without the one-child policy. But a comparison with a broad group of other countries gives a clue.

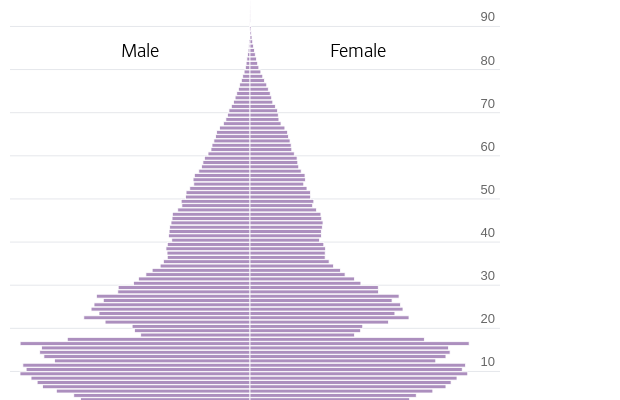

Research by U.N. demographers illustrates how China’s demographic window opened faster and more sharply than in other “less developed” countries, and then closed equally quickly. The population of Chinese aged 20-64—the age when people are most likely to work—grew faster than children and the elderly in the years after the one-child policy was implemented. Before the policy ended, the trajectories had already reversed.

The broader group of other countries shows a smoother ride with the demographic window lasting well into the 2040s.

With China’s opening to the West, it became the world’s factory floor with millions of young people determined to work their way out of poverty. For most of the next decades, Chinese growth topped double-digit percentages.

The optimism was on full display during the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympic Games. When the global financial crisis hit soon after, China kept growth humming and was credited with helping to save the global economy. A few years later, China overtook Japan as the world’s No. 2 economy .

But by 2013, China’s demographic dividend was largely over, according to research by Andrew Mason , an emeritus professor of economics at the University of Hawaii, and Wang Feng , a sociology professor at the University of California, Irvine.

Now, slowing economic growth and demographic changes feed off each other for a gloomy outlook.

“People always count on the [Chinese] government to do more to prop up the economy but the reality is that there’s not a lot the government can do,” Wang said.

Over the next decades, China’s population is likely to show a contrast from, say, India, where the age distribution is following a more natural progression, or the U.S., where immigrant inflows help counteract the aging of the population.

By the end of the century, the U.S. population will be about two-thirds of China’s, compared with less than a quarter now, according to the U.N.’s latest projections. And by then, India, which has overtaken China as the world’s most populous country , will have more than twice as many people as China.

The real demographic impact in China won’t fully hit until the middle of the century, when many of those born during the one-child policy will reach retirement—while still caring for aging parents, said Wang.

By 2050, the U.N. now projects 31% of Chinese will be 65 or older. By 2100, the share will be 46%, approaching half of the population. In the U.S., the share is expected to be 23% and 28%, respectively.

The U.N.’s revised forecasts see Chinese births dropping below nine million this year. In 2022, it had predicted that 10.6 million would be born in China in 2024. The U.N. now expects China will have only 3.1 million newborns a year by 2100.

Not only are there fewer women to give birth these days, but many young women, mindful of their mothers’ suffering during the one-child policy, are less interested in marriage and children , driving down the fertility rate.

As births slip, China’s elderly population is ballooning.

China expects a glut of more than 40 million new retirees—more than the population of Canada—over the five-year period ending in 2025.

The old-age support ratio, a rough indicator of the number of workers for each retiree used by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, is projected to decline from more than four now to fewer than two in 2050, according to The Wall Street Journal’s calculations of the U.N.’s latest data. It will likely reach one worker per retiree by the end of the century.

In reality, due to China’s low retirement age , with women clocking out as early as 50 and men at 60, the support ratio could be even lower.

Beijing as well as demographers and sociologists have said a highly educated population and the advancement of technology such as artificial intelligence, could help China weather such shocks, as more jobs will be automated.

The U.N.’s Gerland said that while the one-child policy was the main demographic event in recent decades, the waxing and waning in different Chinese age groups also reflect tumultuous periods in China’s past, such as the Cultural Revolution and Great Leap Forward, which had substantial demographic impact on the size of the various cohorts born during these years.

“Because of China’s history, the population is going to carry over some of these memories of the past and it will take many generations for all of these past stories to be forgotten,” he said.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

From gorilla encounters in Uganda to a reimagined Okavango retreat, Abercrombie & Kent elevates its African journeys with two spectacular lodge transformations.

The PG rating has become the king of the box office. The entertainment business now relies on kids dragging their parents to theatres.

Selloff in bitcoin and other digital tokens hits crypto-treasury companies.

The hottest crypto trade has turned cold. Some investors are saying “told you so,” while others are doubling down.

It was the move to make for much of the year: Sell shares or borrow money, then plough the cash into bitcoin, ether and other cryptocurrencies. Investors bid up shares of these “crypto-treasury” companies, seeing them as a way to turbocharge wagers on the volatile crypto market.

Michael Saylor pioneered the move in 2020 when he transformed a tiny software company, then called MicroStrategy , into a bitcoin whale now known as Strategy. But with bitcoin and ether prices now tumbling, so are shares in Strategy and its copycats. Strategy was worth around $128 billion at its peak in July; it is now worth about $70 billion.

The selloff is hitting big-name investors, including Peter Thiel, the famed venture capitalist who has backed multiple crypto-treasury companies, as well as individuals who followed evangelists into these stocks.

Saylor, for his part, has remained characteristically bullish, taking to social media to declare that bitcoin is on sale. Sceptics have been anticipating the pullback, given that crypto treasuries often trade at a premium to the underlying value of the tokens they hold.

“The whole concept makes no sense to me. You are just paying $2 for a one-dollar bill,” said Brent Donnelly, president of Spectra Markets. “Eventually those premiums will compress.”

When they first appeared, crypto-treasury companies also gave institutional investors who previously couldn’t easily access crypto a way to invest. Crypto exchange-traded funds that became available over the past two years now offer the same solution.

BitMine Immersion Technologies , a big ether-treasury company backed by Thiel and run by veteran Wall Street strategist Tom Lee , is down more than 30% over the past month.

ETHZilla , which transformed itself from a biotech company to an ether treasury and counts Thiel as an investor, is down 23% in a month.

Crypto prices rallied for much of the year, driven by the crypto-friendly Trump administration. The frenzy around crypto treasuries further boosted token prices. But the bullish run abruptly ended on Oct. 10, when President Trump’s surprise tariff announcement against China triggered a selloff.

A record-long government shutdown and uncertainty surrounding Federal Reserve monetary policy also have weighed on prices.

Bitcoin prices have fallen 15% in the past month. Strategy is off 26% over that same period, while Matthew Tuttle’s related ETF—MSTU—which aims for a return that is twice that of Strategy, has fallen 50%.

“Digital asset treasury companies are basically leveraged crypto assets, so when crypto falls, they will fall more,” Tuttle said. “Bitcoin has shown that it’s not going anywhere and that you get rewarded for buying the dips.”

At least one big-name investor is adjusting his portfolio after the tumble of these shares. Jim Chanos , who closed his hedge funds in 2023 but still trades his own money and advises clients, had been shorting Strategy and buying bitcoin, arguing that it made little sense for investors to pay up for Saylor’s company when they can buy bitcoin on their own. On Friday, he told clients it was time to unwind that trade.

Crypto-treasury stocks remain overpriced, he said in an interview on Sunday, partly because their shares retain a higher value than the crypto these companies hold, but the levels are no longer exorbitant. “The thesis has largely played out,” he wrote to clients.

Many of the companies that raised cash to buy cryptocurrencies are unlikely to face short-term crises as long as their crypto holdings retain value. Some have raised so much money that they are still sitting on a lot of cash they can use to buy crypto at lower prices or even acquire rivals.

But companies facing losses will find it challenging to sell new shares to buy more cryptocurrencies, analysts say, potentially putting pressure on crypto prices while raising questions about the business models of these companies.

“A lot of them are stuck,” said Matt Cole, the chief executive officer of Strive, a bitcoin-treasury company. Strive raised money earlier this year to buy bitcoin at an average price more than 10% above its current level.

Strive’s shares have tumbled 28% in the past month. He said Strive is well-positioned to “ride out the volatility” because it recently raised money with preferred shares instead of debt.

Cole Grinde, a 29-year-old investor in Seattle, purchased about $100,000 worth of BitMine at about $45 a share when it started stockpiling ether earlier this year. He has lost about $10,000 on the investment so far.

Nonetheless, Grinde, a beverage-industry salesman, says he’s increasing his stake. He sells BitMine options to help offset losses. He attributes his conviction in the company to the growing popularity of the Ethereum blockchain—the network that issues the ether token—and Lee’s influence.

“I think his network and his pizzazz have helped the stock skyrocket since he took over,” he said of Lee, who spent 15 years at JPMorgan Chase, is a managing partner at Fundstrat Global Advisors and a frequent business-television commentator.

An opulent Ryde home, packed with cinema, pool, sauna and more, is hitting the auction block with a $1 reserve.

From mud baths to herbal massages, Fiji’s heat rituals turned one winter escape into a soul-deep reset.