How IKEA Chopped, Hollowed Out and Flattened Its Furniture to Cut Costs

With inflation squeezing consumers and material and shipping prices up, the company took products back to the drawing board

ÄLMHULT, Sweden—Amid IKEA’s colourful staged living rooms, piles of umlaut-laden housewares and endless rows of flat-pack boxes is furniture that can have shoppers wondering: How does that chair cost only $35?

IKEA grew into a furniture behemoth with a relentless focus on keeping costs low, but that goal has become more challenging. The price of metal, glass, wood and plastic have spiralled up, as have shipping costs. Inflation has squeezed consumers’ wallets. Managers at IKEA knew that something had to change to keep prices down and profits up, so in the past couple of years they have taken some of their products back to the drawing board.

Designers experimented with ways to reduce IKEA’s reliance on wood—even in its trademark wooden furniture—to cut material and shipping costs. Lighter, less expensive plastics, they discovered, could be used instead in cabinet doors and drawers.

They learned that they could substitute less expensive recycled aluminium for zinc, which had doubled in price over two years to $4,371 per metric ton after the start of the Ukraine war. Recycled aluminium is now going into bathroom hooks and other products.

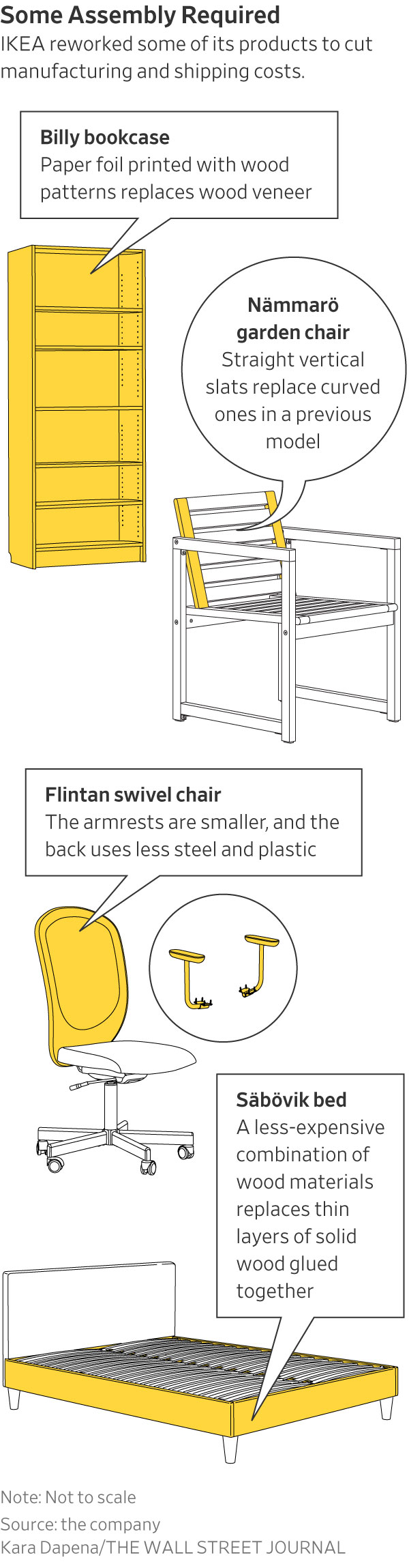

When they turned to packaging, they cut freight costs by purging flat packs of “fresh air and wasted space,” said Fredrika Inger, IKEA’s global range manager. On the new Nämmarö garden chair, the curved wooden slats featured on a previous model were straightened, which allowed the components to be packed more tightly together.

“Our budget is the customer’s wallet, and their wallets are smaller than ever,” said Susanne Waidzunas, global supply manager at Inter IKEA Holding BV, the company that owns the IKEA brand, develops its products and manages its supply chain.

Based in Älmhult in southern Sweden, where the late Ingvar Kamprad founded the company eight decades ago, IKEA is today the world’s biggest seller of furniture, with 460 mostly franchise-operated stores spread across 62 countries that carry some 9,500 products. Its in-store canteens serve 1 billion Swedish meatballs with cream sauce and lingonberry jam each year.

Mr. Kamprad, who died in 2018, believed in “democratic design”—essentially that everyday products should be attractive and functional, but also affordable. It was, in part, a hard-nosed strategy designed to maximize sales.

The challenges started with the disruptions of the Covid-19 pandemic, compounded by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Then high inflation presented many companies with a dilemma: raise prices to offset growing costs and risk alienating customers, or keep prices down and sacrifice profit margins. IKEA did some of both last year, and its annual profit halved, to 710 million euros, equivalent to $778 million, despite record sales.

As part of its push to boost profits, the company said last week it would spend 2 billion euros to open new U.S. locations over the next three years—its largest-ever investment in new American stores.

One of the company’s chief weapons in its fight to cut costs is the Billy bookcase, a bestseller considered the “heart of IKEA,” said Jesper Samuelsson, the product’s manager. Over 140 million units have been sold since it first appeared in the 1979 edition of the IKEA catalog. The company says someone, somewhere buys a Billy every five seconds—which comes out to around 6.3 million sales a year.

According to IKEA’s official history, the Billy’s original design was scribbled on a napkin after its creator, Gillis Lundgren, was inspired by criticism from IKEA’s then-advertising manager that the company’s bookcases lacked simplicity.

Now, Mr. Samuelsson said, IKEA colleagues have a game they play: “If you’re a product in IKEA, which one are you? I’m Billy—it’s a very simple, straightforward product.”

The Billy comes in two styles: white and wood finish. Its last major overhaul came in 1999, when the company changed its method for producing the white version. IKEA designers knocked a fifth off the unit’s price by replacing its white lacquer coating with a melamine foil.

It has been significantly cheaper than the wood-finish version ever since. In the U.S., the model that measures roughly 6½ feet tall and 2½ feet wide retails at $89.99 in white and $109.99 in wood finish. IKEA executives wanted to make the latter version less expensive, too, said Mr. Samuelsson.

Targeting a cost savings of 25% to 30%, Mr. Samuelsson and his colleagues focused on a solution that IKEA had been developing for years: the replacement of wood veneer with paper foil.

IKEA’s wooden furniture isn’t typically made of solid wood. Instead, it has traditionally used veneer, a thin slice of wood less than a millimetre thick that is glued onto a main structure of particleboard. Particleboard is formed from compacted wood chips and sawdust, and is significantly less expensive and lighter than solid wood.

Mr. Samuelsson knew that getting rid of the costly veneer would be key to savings, he said. The paper foil is less expensive, less wasteful and much quicker to apply than veneer, which speeds up the rate of production, Mr. Samuelsson said. Wrapped around the particleboard structure and printed with wood patterns, it looks like a wooden surface, he said.

IKEA first began to develop paper foil for use on its furniture around 2004, and has since steadily made the material less expensive and more reliable, gradually deploying it on other furniture lines, including the Pax wardrobe, one of the company’s bestselling bedroom closets.

By the time Mr. Samuelsson and his team of a dozen designers set about reworking the Billy in 2020, IKEA leaders had enough confidence in the paper foil to use it on their prize bookcase, he said. The Billy redesign brought some functional changes—including the replacement of metal nails with user-friendly plastic fasteners—but the switch from veneer to foil generated the cost savings that managers had been hoping for, he said.

The global rollout of the reworked version of the bookcase—produced in Sweden, Germany, Slovakia and China—has faced obstacles. Factories in Europe were already running at capacity, so the company would need to move slowly and carefully to introduce the new version without disrupting output. IKEA also realised its demand for paper foil would balloon, which required lengthy preparations to help suppliers build up their output.

Production of the new version started last year in China, where the local manufacturer had spare capacity and could implement the new production system sooner. The Billy is the country’s No. 1 IKEA product. There the wood-style bookcase is priced at 499 yuan, equivalent to about $72, down from 699 yuan—a 29% reduction. The white version sells for 399 yuan. The new Billy hits stores in the U.S. and Europe in early 2024.

These kinds of design changes are unlikely to alienate IKEA consumers, who typically don’t focus on how their furniture is made, said Tom Higgs, a furniture designer and lecturer at London’s Brunel University. “IKEA’s customers are looking for affordable, replaceable and convenient furniture,” he said.

For one of IKEA’s most popular office swivel chairs, the Flintan, smaller armrests and less steel and plastic in the back cut manufacturing costs. The new Flintan, which hit stores in 2021, is roughly the same size as its predecessor, but it’s much more efficient to ship after designers tweaked its components to make them fit more snugly into a flat pack. IKEA can now squeeze 6,900 Flintans into one shipping container, up from 2,750.

Even so, the company said that costs have increased so much that it decided to hold the chair’s price at $119 in the U.S. Without the design tweaks, the price would have risen significantly, it said.

IKEA designers likewise reworked the Säbövik bed, available in Europe but not the U.S., by changing the construction of its wooden frame. It was previously made of so-called sandwich board, comprising thin layers of wood glued together. Designers experimented with new material mixes before settling on a less expensive and lighter combination of solid wood, plywood and a compressed structure of wood strands and glue called oriented strand board.

The Säbövik used to come flat-packed in three cardboard boxes, but now fits into just two more compact boxes, enabling the company to cram twice as many flat-packed beds into a shipping container.

Tasked with developing a new extendible dining table that wouldn’t be prohibitively expensive, IKEA designers tried a novel approach.

Earlier IKEA tables typically used solid wood legs for strength and stability. In developing the new Rönninge table, which launched last year, designers created a leg made from hollow wood veneer with solid-wood inserts at the top and bottom to add strength. This approach significantly reduces material and freight costs since each leg now contains 90% less wood than if it had been made of solid wood, the company said. The Rönninge retails at $499 in the U.S.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

No trip to Singapore is complete without a meal (or 12) at its hawker centres, where stalls sell multicultural dishes from generations-old recipes. But rising costs and demographic change are threatening the beloved tradition.

In Singapore, it’s not unusual for total strangers to ask, “Have you eaten yet?” A greeting akin to “Good morning,” it invariably leads to follow-up questions. What did you eat? Where did you eat it? Was it good? Greeters reserve the right to judge your responses and offer advice, solicited or otherwise, on where you should eat next.

Locals will often joke that gastronomic opinions can make (and break) relationships and that eating is a national pastime. And why wouldn’t it be? In a nexus of colliding cultures—a place where Malays, Indians, Chinese and Europeans have brushed shoulders and shared meals for centuries—the mix of flavours coming out of kitchens in this country is enough to make you believe in world peace.

While Michelin stars spangle Singapore’s restaurant scene , to truly understand the city’s relationship with food, you have to venture to the hawker centres. A core aspect of daily life, hawker centres sprang up in numbers during the 1970s, built by authorities looking to sanitise and formalise the city’s street-food scene. Today, 121 government-run hawker centres feature food stalls that specialise in dishes from the country’s various ethnic groups. In one of the world’s most expensive cities, hawker dishes are shockingly cheap: A full meal can cost as little as $3.

Over the course of many visits to Singapore, I’ve fallen in love with these places—and with the scavenger hunts to find meals I’ll never forget: delicate bowls of laksa noodle soup, where brisk lashes of heat interrupt addictive swirls of umami; impossibly flaky roti prata dipped in curry; the beautiful simplicity of an immaculately roasted duck leg. In a futuristic and at times sterile city, hawker centres throw back to the past and offer a rare glimpse of something human in scale. To an outsider like me, sitting at a table amid the din of the lunch-hour rush can feel like glimpsing the city’s soul through all the concrete and glitz.

So I’ve been alarmed in recent years to hear about the supposed demise of hawker centres. Would-be hawkers have to bid for stalls from the government, and rents are climbing . An upwardly mobile generation doesn’t want to take over from their parents. On a recent trip to Singapore, I enlisted my brother, who lives there, and as we ate our way across the city, we searched for signs of life—and hopefully a peek into what the future holds.

At Amoy Street Food Centre, near the central business district, 32-year-old Kai Jin Thng has done the math. To turn a profit at his stall, Jin’s Noodle , he says, he has to churn out at least 150 $4 bowls of kolo mee , a Malaysian dish featuring savoury pork over a bed of springy noodles, in 120 minutes of lunch service. With his sister as sous-chef, he slings the bowls with frenetic focus.

Thng dropped out of school as a teenager to work in his father’s stall selling wonton mee , a staple noodle dish, and is quick to say no when I ask if he wants his daughter to take over the stall one day.

“The tradition is fading and I believe that in the next 10 or 15 years, it’s only going to get worse,” Thng said. “The new generation prefers to put on their tie and their white collar—nobody really wants to get their hands dirty.”

In 2020, the National Environment Agency , which oversees hawker centres, put the median age of hawkers at 60. When I did encounter younger people like Thng in the trade, I found they persevered out of stubbornness, a desire to innovate on a deep-seated tradition—or some combination of both.

Later that afternoon, looking for a momentary reprieve from Singapore’s crushing humidity, we ducked into Market Street Hawker Centre and bought juice made from fresh calamansi, a small citrus fruit.

Jamilah Beevi, 29, was working the shop with her father, who, at 64, has been a hawker since he was 12. “I originally stepped in out of filial duty,” she said. “But I find it to be really fulfilling work…I see it as a generational shop, so I don’t want to let that die.” When I asked her father when he’d retire, he confidently said he’d hang up his apron next year. “He’s been saying that for many years,” Beevi said, laughing.

More than one Singaporean told me that to truly appreciate what’s at stake in the hawker tradition’s threatened collapse, I’d need to leave the neighbourhoods where most tourists spend their time, and venture to the Heartland, the residential communities outside the central business district. There, hawker centres, often combined with markets, are strategically located near dense housing developments, where they cater to the 77% of Singaporeans who live in government-subsidised apartments.

We ate laksa from a stall at Ghim Moh Market and Food Centre, where families enjoyed their Sunday. At Redhill Food Centre, a similar chorus of chattering voices and clattering cutlery filled the space, as diners lined up for prawn noodles and chicken rice. Near our table, a couple hungrily unwrapped a package of durian, a coveted fruit banned from public transportation and some hotels for its strong aroma. It all seemed like business as usual.

Then we went to Blackgoat . Tucked in a corner of the Jalan Batu housing development, Blackgoat doesn’t look like an average hawker operation. An unusually large staff of six swirled around a stall where Fikri Amin Bin Rohaimi, 24, presided over a fiery grill and a seriously ambitious menu. A veteran of the three-Michelin-star Zén , Rohaimi started selling burgers from his apartment kitchen in 2019, before opening a hawker stall last year. We ordered everything on the menu and enjoyed a feast that would astound had it come out of a fully equipped restaurant kitchen; that it was all made in a 130-square-foot space seemed miraculous.

Mussels swam in a mushroom broth, spiked with Thai basil and chives. Huge, tender tiger prawns were grilled to perfection and smothered in toasted garlic and olive oil. Lamb was coated in a whisper of Sichuan peppercorns; Wagyu beef, in a homemade makrut-lime sauce. Then Ethel Yam, Blackgoat’s pastry chef prepared a date pudding with a mushroom semifreddo and a panna cotta drizzled in chamomile syrup. A group of elderly residents from the nearby towers watched, while sipping tiny glasses of Tiger beer.

Since opening his stall, Rohaimi told me, he’s seen his food referred to as “restaurant-level hawker food,” a categorisation he rejects, feeling it discounts what’s possible at a hawker centre. “If you eat hawker food, you know that it can often be much better than anything at a restaurant.”

He wants to open a restaurant eventually—or, leveraging his in-progress biomedical engineering degree, a food lab. But he sees the modern hawker centre not just as a steppingstone, but a place to experiment. “Because you only have to manage so many things, unlike at a restaurant, a hawker stall right now gives us a kind of limitlessness to try new things,” he said.

Using high-grade Australian beef and employing a whole staff, Rohaimi must charge more than typical hawker stalls, though his food, around $12 per 100 grams of steak, still costs far less than high-end restaurant fare. He’s found that people will pay for quality, he says, even if he first has to convince them to try the food.

At Yishun Park Hawker Centre (now temporarily closed for renovations), Nurl Asyraffie, 33, has encountered a similar dynamic since he started Kerabu by Arang , a stall specialising in “modern Malay food.” The day we came, he was selling ayam percik , a grilled chicken leg smothered in a bewitching turmeric-based marinade. As we ate, a hawker from another stall came over to inquire how much we’d paid. When we said around $10 a plate, she looked skeptical: “At least it’s a lot of food.”

Asyraffie, who opened the stall after a spell in private dining and at big-name restaurants in the region, says he’s used to dubious reactions. “I think the way you get people’s trust is you need to deliver,” he said. “Singapore is a melting pot; we’re used to trying new things, and we will pay for food we think is worth it.” He says a lot of the same older “uncles” who gawked at his prices, are now regulars. “New hawkers like me can fill a gap in the market, slightly higher than your chicken rice, but lower than a restaurant.”

But economics is only half the battle for a new generation of hawkers, says Seng Wun Song, a 64-year-old, semiretired economist who delves into the inner workings of Singapore’s food-and-beverage industry as a hobby. He thinks locals and tourists who come to hawker centers to look for “authentic” Singaporean food need to rethink what that amorphous catchall word really means. What people consider “heritage food,” he explains, is a mix of Malay, Chinese, Indian and European dishes that emerged from the country’s founding. “But Singapore is a trading hub where people come and go, and heritage moves and changes. Hawker food isn’t dying; it’s evolving so that it doesn’t die.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.