America Had ‘Quiet Quitting.’ In China, Young People Are ‘Letting It Rot.’

Demoralized by a weak economy and unfulfilling jobs, young Chinese are dropping out, exploring spirituality and becoming more rebellious, presenting new challenges for Beijing

China’s ruling Communist Party wants the country’s young people to be ambitious, work hard and prepare for adversity.

Li Jiajia just wants to win the lottery.

Demoralised by a weak economy, unfulfilling jobs and a paternalistic state, young Chinese such as Li are looking for pathways out of the carefully scripted lives their elders want for them, putting themselves at odds with the country’s priorities.

After moving to Beijing from her hometown in southeastern China in April, the 24-year-old Li found her new job as a content creator at a technology startup uninspiring. She said she has no desire to climb the corporate ladder, especially when the number of high-paying Chinese tech jobs is shrinking.

The ever-present role of the state in daily life is stultifying, she said. Though she wanted to be a journalist in high school, she gave up when she realised how heavily the government censors the media.

She says she knows she probably won’t win the lottery. But when she plays, at least she can dream of a better life—most likely abroad.

“I want to leave here and live the life I want,” Li said. “It won’t happen overnight, but for now, the thrill of scratching lottery tickets gives me a little break.”

Since China’s government cracked down on disaffected students in Tiananmen Square in 1989, most young people, who came of age in an era of rapid economic growth and rising affluence, have done what they are supposed to do—and been rewarded for it.

They studied diligently to get into prestigious universities, clocked gruelling hours at fast-growing companies and followed traditional expectations of career and family, riding China’s boom to material success.

Many are still doing that. But a growing number of middle-class urbanites in their 20s and 30s in China have begun to question that trajectory, if not reject it entirely, as prospects of upward mobility fade.

More than two years of harsh government Covid controls left some pondering the role of the Communist Party and other sources of authority in their lives, or even the meaning of life and who they aspire to be—questions many had never contemplated before.

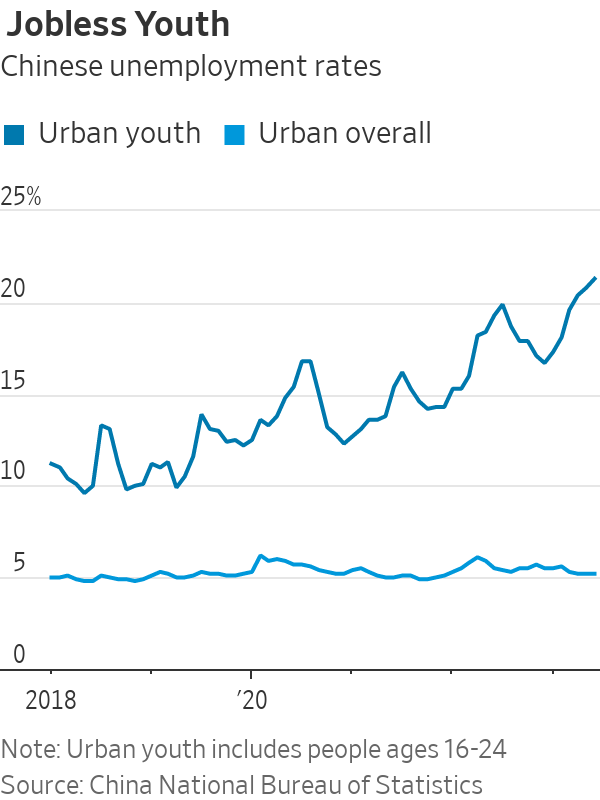

Record youth unemployment that topped 21% this year has further dented confidence in traditional paths to achievement in China. Some, like Li, are also frustrated about other issues, such as violence against women in China or government efforts to prevent people from accessing foreign apps such as Twitter or Instagram.

Many are quitting their jobs and turning to meditation and other forms of spirituality. Some are moving far from China’s megacities to start lives anew in places like Dali, a southwestern city famous within China as a hub for digital nomads and dropouts.

Others are flooding fortune-teller stands and Buddhist temples in mountainous areas, or exploring Chinese and Western philosophers and writers from Laozi to Hermann Hesse. Some are throwing “quitting parties” with banners celebrating their newfound freedom.

“This generation has had a lot of resources invested in them,” said Sara Friedman, professor of anthropology and gender studies at Indiana University, who studies Chinese society.

“They have worked really hard. They have been pushed really hard. And to then say, ‘I’m stepping out of this rat race, I’m opting out,’ is a pretty radical decision to be making.”

From ‘lying flat’ to ‘letting it rot’

Social-media discussions about temple visits and anxiety—a central preoccupation of many young Chinese—have surged in 2023, according to BigOne Lab, a research firm.

About 34% of surveyed respondents in their mid-20s quit or were considering resigning from jobs in China’s consumer internet sector—a major employer of young people—in the first half of 2023, according to China’s job-seeking and social platform Maimai.

Playing the lottery has become especially trendy for 20- and 30-somethings, whose purchases of lottery tickets helped push sales to $67 billion from January to October, a 53% jump from the previous year and averaging $48 per person in China.

Catchphrases describing the mood have worked their way into everyday discourse. First, in 2020, was the arcane sociological term neijuan, or “involution,” which referred to situations in which people work hard and compete without anyone getting ahead.

That was followed by “touching fish.” The phrase, borrowed from a Chinese idiom, referred to executing small rebellions at work, such as taking long toilet breaks, doing online shopping or reading novels in the office.

Next was “lying flat,” a form of mundane resistance that involves dragging one’s feet at work or dropping out of the workforce altogether. Last year, the phrase “let it rot” spread to describe young people who have completely given up.

A survey conducted by Tsingyan Group, a research firm, last year found that approximately 96% of nearly 6,000 respondents in China were aware of people “lying flat” to various degrees in their vicinity. The concept held more appeal among people ages 26 to 40 than other Chinese, the survey showed.

“It’s a very passive form of resistance,” said Silvia Lindtner, an ethnographer at the University of Michigan. “It’s definitely a very difficult moment, but it could also be seen as a hopeful moment where there is pressure, in some ways, on the leadership.”

Echoes of the 1960s

In some ways the ennui resembles the “quiet quitting” phenomenon of post pandemic America—or, going back further, the rejection of social norms by young people across the Western world in the 1960s.

In those days, two decades of fast economic growth and wider affluence gave young people more choices than previous generations. Many responded by challenging their parents’ way of life.

In China, where open protests are rarely possible, young people are now rebelling in other ways.

“Lying flat is a latent resistance to the moral blackmailing of society,” said Amy Yan, a 27-year-old Shenzhen resident who once worked as a buyer for her family’s export business. When the business went bankrupt last year after her parents lost their assets in a financial scam, it reinforced her belief that she should give priority to her spirituality.

Even before the bankruptcy, she had decided that accepting the corporate grind and meeting traditional expectations of marriage and children would interfere with her desire to explore her spirituality.

Following the family crisis, she put her savings of $27,000 into supporting a tiny Taoist ashram she had started with a few fellow practitioners.

Coming into Beijing’s crosshairs

Communist Party leaders have long worried young people could stir unrest, as they did in 1989. The party needs young people to get on board with Beijing’s priorities, not just to keep the economy humming and avoid instability, but to help make China stronger in an era of great-power competition with the U.S.

In a speech at last year’s Communist Party congress, widely quoted in Chinese media, leader Xi Jinping laid out his vision for young people, urging them to have “ideals, courage, a willingness to endure hardship and a dedication to strive” to help “build a modernised socialist country.”

In a 2021 article published in the top party journal Qiushi, he specifically warned against “lying flat.” Discussions of the phenomenon have often triggered censorship online.

If all the young people who had dropped out of China’s labor force and relied financially on their parents were counted, China’s real youth unemployment rate could be as high as 46.5%, according to calculations earlier this year by a Peking University professor.

The Communist Party Youth League—with more than 70 million members—has published commentary on its official WeChat account criticising college graduates for having too much pride. Job seekers “should not refuse to enter the workforce due to the difficulty of finding a job or choose to ‘lie flat’ out of fear of ‘involution,’” the article read.

Greater affluence—but an uncertain future

Until recently, China’s economic progress seemed to be unstoppable, with per-capita incomes surging to around $13,000 in 2022 from less than $1,000 in 2000, according to the World Bank.

But economic growth has slowed. Many economists worry China could get stuck in the “middle-income trap,” in which a country’s progress plateaus before it gets rich. Per-capita incomes in the U.S. were around $76,000 last year.

Academic research shows that social mobility for many groups in China has stalled, meaning it has become harder for people without connections to get ahead.

Many employers that young people gravitated to, including Alibaba, Tencent and ByteDance, have been shedding staff amid weak growth and government clampdowns on the private sector. Tech salaries have declined in the past three years, according to Maimai, and opportunities for initial public offering payouts have faded, leaving many who used to work “996” schedules—9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week—wondering what the point was.

It is also true that many more middle-class young people—especially those without children and mortgages—can afford to drop out of the rat race today than in previous eras.

Some plan to leave: Net emigration from China, which fell to 125,000 in 2012 as the country’s economy boomed, rebounded to more than 310,000 in the first 11 months of 2023, according to United Nations data.

Others want to stay—but on their own terms.

Huang Xialu quit her high-stress job as a product manager at one of China’s largest video-streaming companies in April, so she could focus more on spiritual retreats. For a long time before that, the 33-year-old said she had struggled with a lack of purpose.

“I had a very urgent sense that if I didn’t listen to my gut and take a break to explore what I truly wanted to do in this world, it would be too late,” she said.

In the months following Huang’s resignation, she traveled to Dali, where she worked on a tarot-reading stand, took a training course in life coaching and learned to make pottery.

To Huang, lying flat is the opposite of being passive—it is a path for taking control of one’s own life when wading through uncertain terrain, she said.

Now she has become a certified life coach, helping individuals who are as confused as she was to find a way forward. Her income is less stable.

But “I haven’t regretted quitting for a second,” she said.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

The remote northern island wants more visitors: ‘It’s the rumbling before the herd is coming,’ one hotel manager says

As European hot spots become overcrowded , travellers are digging deeper to find those less-populated but still brag-worthy locations. Greenland, moving up the list, is bracing for its new popularity.

Aria Varasteh has been to 69 countries, including almost all of Europe. He now wants to visit more remote places and avoid spots swarmed by tourists—starting with Greenland.

“I want a taste of something different,” said the 34-year-old founder of a consulting firm serving clients in the Washington, D.C., area.

He originally planned to go to Nuuk, the island’s capital, this fall via out-of-the-way connections, given there wasn’t a nonstop flight from the U.S. But this month United Airlines announced a nonstop, four-hour flight from Newark Liberty International Airport in New Jersey to Nuuk. The route, beginning next summer, is a first for a U.S. airline, according to Greenland tourism officials.

It marks a significant milestone in the territory’s push for more international visitors. Airlines ran flights with a combined 55,000 seats to Greenland from April to August of this year, says Jens Lauridsen, chief executive officer of Greenland Airports. That figure will nearly double next year in the same period, he says, to about 105,000 seats.

The possible coming surge of travellers also presents a challenge for a vast island of 56,000 people as nearby destinations from Iceland to Spain grapple with the consequences of over tourism.

Greenlandic officials say they have watched closely and made deliberate efforts to slowly scale up their plans for visitors. An investment north of $700 million will yield three new airports, the first of which will open next month in Nuuk.

“It’s the rumbling before the herd is coming,” says Mads Mitchell, general manager of Hotel Nordbo, a 67-room property in Nuuk. The owner of his property is considering adding 50 more rooms to meet demand in the coming years.

Mitchell has recently met with travel agents from Brooklyn, N.Y., South Korea and China. He says he welcomes new tourists, but fears tourism will grow too quickly.

“Like in Barcelona, you get tired of tourists, because it’s too much and it pushes out the locals, that is my concern,” he says. “So it’s finding this balance of like showing the love for Greenland and showing the amazing possibilities, but not getting too much too fast.”

Greenland’s buildup

Greenland is an autonomous territory of Denmark more than three times the size of Texas. Tourists travel by boat or small aircraft when venturing to different regions—virtually no roads connect towns or settlements.

Greenland decided to invest in airport infrastructure in 2018 as part of an effort to expand tourism and its role in the economy, which is largely dependent on fishing and subsidies from Denmark. In the coming years, airports in Ilulissat and Qaqortoq, areas known for their scenic fjords, will open.

One narrow-body flight, like what United plans, will generate $200,000 in spending, including hotels, tours and other purchases, Lauridsen says. He calls it a “very significant economic impact.”

In 2023, foreign tourism brought a total of over $270 million to Greenland’s economy, according to Visit Greenland, the tourism and marketing arm owned by the government. Expedition cruises visit the territory, as well as adventure tours.

United will fly twice weekly to Nuuk on its 737 MAX 8, which will seat 166 passengers, starting in June .

“We look for new destinations, we look for hot destinations and destinations, most importantly, we can make money in,” Andrew Nocella , United’s chief commercial officer, said in the company’s earnings call earlier in October.

On the runway

Greenland has looked to nearby Iceland to learn from its experiences with tourism, says Air Greenland Group CEO Jacob Nitter Sørensen. Tiny Iceland still has about seven times the population of its western neighbour.

Nuuk’s new airport will become the new trans-Atlantic hub for Air Greenland, the national carrier. It flies to 14 airports and 46 heliports across the territory.

“Of course, there are discussions about avoiding mass tourism. But right now, I think there is a natural limit in terms of the receiving capacity,” Nitter says.

Air Greenland doesn’t fly nonstop from the U.S. because there isn’t currently enough space to accommodate all travellers in hotels, Nitter says. Air Greenland is building a new hotel in Ilulissat to increase capacity when the airport opens.

Nuuk has just over 550 hotel rooms, according to government documents. A tourism analysis published by Visit Greenland predicts there could be a shortage in rooms beginning in 2027. Most U.S. visitors will stay four to 10 nights, according to traveler sentiment data from Visit Greenland.

As travel picks up, visitors should expect more changes. Officials expect to pass new legislation that would further regulate tourism in time for the 2025 season. Rules on zoning would give local communities the power to limit tourism when needed, says Naaja H. Nathanielsen, minister for business, trade, raw materials, justice and gender equality.

Areas in a so-called red zone would ban tour operators. In northern Greenland, traditional hunting takes place at certain times of year and requires silence, which doesn’t work with cruise ships coming in, Nathanielsen says.

Part of the proposal would require tour operators to be locally based to ensure they pay taxes in Greenland and so that tourists receive local knowledge of the culture. Nathanielsen also plans to introduce a proposal to govern cruise tourism to ensure more travelers stay and eat locally, rather than just walk around for a few hours and grab a cup of coffee, she says.

Public sentiment has remained in favour of tourism as visitor arrivals have increased, Nathanielsen says.

—Roshan Fernandez contributed to this article.

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.