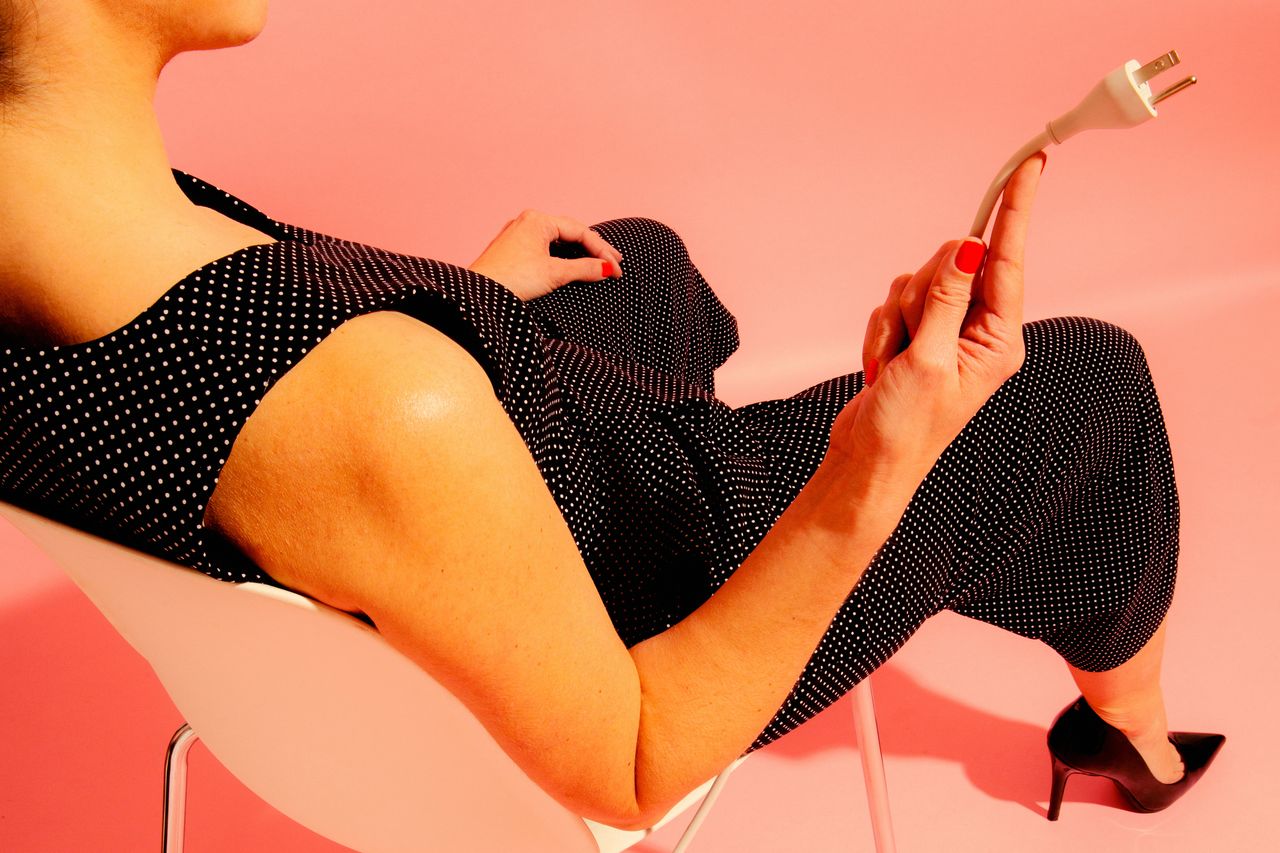

Can You Get Ahead and Still Have a Life? Younger Women Are Trying to Find Out

Women assessing their careers say they’re determined to advance while keeping work-life boundaries intact

Deijha Martin, 26 years old, works as a data analyst from her Bronx, N.Y., apartment. On workdays, she’ll chip away at a task until 5:10 p.m. or 5:20 p.m., but never 6 p.m. She loves travel, and earlier this year tapped her company’s unlimited vacation policy to jet to Greece and France.

Having boundaries is a priority, but make no mistake: She’s plenty ambitious.

“I definitely do want to make money,” she says, so that she can fund the things she loves to do. “It’s just, not really fighting with anyone to get to the top.”

The pandemic’s shake-up of work and life has had lasting effects on ambition for a lot of women. For some, the last years have prompted a reassessment of how much they’re willing to give to their careers at the expense of family time or outside interests. For others, many of them younger professionals, seeing the ways other leaders have allowed work to subsume their lives is a turnoff. And after a spell of workplace flexibility few would have imagined before 2020, many women are now asking the question: Can you get ahead and still have a life?

“The company’s not hinging on your ability to answer an email at 11 o’clock p.m.,” says Alexis Koeppen, a 31-year-old technology worker in New Orleans. “The work will always be there for you.”

She quit an intense consulting job in Washington, D.C., moved to New Orleans to be with her boyfriend and switched to a remote role that gives her time to walk her dog, a pandemic addition, and exercise. Instead of taking on extra work, she’s leaning into trips with friends, weddings, parties. “We didn’t get to for so long,” she says.

Plenty of men are rethinking their relationship with work, too. Women face a particular combination of pressures and penalties at home and on the job. They shoulder far more housework and child care, according to government data, and research shows colleagues perceive them as less committed to their jobs when they become pregnant.

Getting ahead without being always-on might be a hard ask.

“The workplace is still designed for people where work is the number-one priority all the time,” says Ellen Ernst Kossek, a management professor at Purdue University who studies gender and work.

Workers who make themselves constantly available receive better performance evaluations, more promotions and faster earnings growth, adds Youngjoo Cha, a professor of sociology at Indiana University Bloomington. The current economic moment, marked by inflation and the threat of recession, makes the idea of pulling back at work risky yet enticing.

“You think, ‘Are they going to think I’m not a team player?’ Or not come back to me with opportunities, or think I’m ungrateful?” says Kim Kaupe, the Austin, Texas-based co-founder of a marketing agency. She has constructed an email template, which she fires off at least once a month, declining new work opportunities to preserve time for her personal life. Still, she worries.

“I hope they know that I’m still ambitious,” Ms. Kaupe, 37, says of her clients and people reaching out with new opportunities. “But I don’t know.”

Ms. Koeppen says she once aspired to reach the C-suite, but seeing top management up close changed her mind. “I don’t want to be those people,” she says. “They don’t seem happy to me.”

Almost two-thirds of women under 30 surveyed by McKinsey & Co. and LeanIn.Org, the nonprofit founded by Sheryl Sandberg, say they would be more eager to advance if they saw senior leaders who had the work-life balance they desire. A good number of senior women leaders themselves aren’t happy either. About 43% of female leaders say they are burned out, the survey data show, as compared with 31% of male leaders.

While some younger women seek a finite workday, baby boomers and Gen Xers wonder whether they could have done things differently and still gotten ahead.

“I don’t know that I did it the right way,” says Jory Des Jardins, a 50-year-old marketing executive, who describes dropping everything for her career and delaying a family until her late 30s.

A co-founder of BlogHer, an online community for women, she spent years travelling frequently for work, transporting her breastmilk home to the San Francisco Bay Area after she had two daughters at age 38 and 40. Her husband paused his career to stay home.

“We wanted to show women it could be done and that we could run a business,” she says of the BlogHer leadership. “We didn’t want to disappoint.”

Ms. Des Jardins eventually sold her company, and tried to dial back professionally. But she had set a precedent as an all-in worker. The opportunities that came her way required flying to New York every week and prioritising an investor meeting over all else.

The pandemic gave her a chance to derive comfort from her family instead of achievements, to unapologetically embrace her whole life, she says. Now she’s wondering, what next?

“If you’re not integrating your life along the way, you kind of have an identity crisis later,” says Ms. Des Jardins, who now works for a startup. “Would it have been that awful if we had taken a little time? Would we have completely taken a step back? I don’t think so. But that was a bet that we weren’t going to take.”

Loria Yeadon, a lawyer who rose to be chief executive of the YMCA of Greater Seattle, still remembers the moment 15 years ago when, rushing to her child’s kindergarten-graduation ceremony, her company’s general counsel rang. Ms. Yeadon said she had 10 minutes to talk. The conversation stretched for an hour.

She didn’t hang up the phone. “I didn’t feel the freedom to do it,” she says.

She made it to her daughter’s ceremony, but spent the beginning still on the call in the back of the room. Looking back, she wishes she had hung up the phone.

“I think today I would just throw it to the wind and trust that there would be another job, or that I’d be fine where I am,” she says. “That I could still have the career I longed for.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

As Paris makes its final preparations for the Olympic games, its residents are busy with their own—packing their suitcases, confirming their reservations, and getting out of town.

Worried about the hordes of crowds and overall chaos the Olympics could bring, Parisians are fleeing the city in droves and inundating resort cities around the country. Hotels and holiday rentals in some of France’s most popular vacation destinations—from the French Riviera in the south to the beaches of Normandy in the north—say they are expecting massive crowds this year in advance of the Olympics. The games will run from July 26-Aug. 1.

“It’s already a major holiday season for us, and beyond that, we have the Olympics,” says Stéphane Personeni, general manager of the Lily of the Valley hotel in Saint Tropez. “People began booking early this year.”

Personeni’s hotel typically has no issues filling its rooms each summer—by May of each year, the luxury hotel typically finds itself completely booked out for the months of July and August. But this year, the 53-room hotel began filling up for summer reservations in February.

“We told our regular guests that everything—hotels, apartments, villas—are going to be hard to find this summer,” Personeni says. His neighbours around Saint Tropez say they’re similarly booked up.

As of March, the online marketplace Gens de Confiance (“Trusted People”), saw a 50% increase in reservations from Parisians seeking vacation rentals outside the capital during the Olympics.

Already, August is a popular vacation time for the French. With a minimum of five weeks of vacation mandated by law, many decide to take the entire month off, renting out villas in beachside destinations for longer periods.

But beyond the typical August travel, the Olympics are having a real impact, says Bertille Marchal, a spokesperson for Gens de Confiance.

“We’ve seen nearly three times more reservations for the dates of the Olympics than the following two weeks,” Marchal says. “The increase is definitely linked to the Olympic Games.”

Getty Images

According to the site, the most sought-out vacation destinations are Morbihan and Loire-Atlantique, a seaside region in the northwest; le Var, a coastal area within the southeast of France along the Côte d’Azur; and the island of Corsica in the Mediterranean.

Meanwhile, the Olympics haven’t necessarily been a boon to foreign tourism in the country. Many tourists who might have otherwise come to France are avoiding it this year in favour of other European capitals. In Paris, demand for stays at high-end hotels has collapsed, with bookings down 50% in July compared to last year, according to UMIH Prestige, which represents hotels charging at least €800 ($865) a night for rooms.

Earlier this year, high-end restaurants and concierges said the Olympics might even be an opportunity to score a hard-get-seat at the city’s fine dining.

In the Occitanie region in southwest France, the overall number of reservations this summer hasn’t changed much from last year, says Vincent Gare, president of the regional tourism committee there.

“But looking further at the numbers, we do see an increase in the clientele coming from the Paris region,” Gare told Le Figaro, noting that the increase in reservations has fallen directly on the dates of the Olympic games.

Michel Barré, a retiree living in Paris’s Le Marais neighbourhood, is one of those opting for the beach rather than the opening ceremony. In January, he booked a stay in Normandy for two weeks.

“Even though it’s a major European capital, Paris is still a small city—it’s a massive effort to host all of these events,” Barré says. “The Olympics are going to be a mess.”

More than anything, he just wants some calm after an event-filled summer in Paris, which just before the Olympics experienced the drama of a snap election called by Macron.

“It’s been a hectic summer here,” he says.

AFP via Getty Images

Parisians—Barré included—feel that the city, by over-catering to its tourists, is driving out many residents.

Parts of the Seine—usually one of the most popular summertime hangout spots —have been closed off for weeks as the city installs bleachers and Olympics signage. In certain neighbourhoods, residents will need to scan a QR code with police to access their own apartments. And from the Olympics to Sept. 8, Paris is nearly doubling the price of transit tickets from €2.15 to €4 per ride.

The city’s clear willingness to capitalise on its tourists has motivated some residents to do the same. In March, the number of active Airbnb listings in Paris reached an all-time high as hosts rushed to list their apartments. Listings grew 40% from the same time last year, according to the company.

With their regular clients taking off, Parisian restaurants and merchants are complaining that business is down.

“Are there any Parisians left in Paris?” Alaine Fontaine, president of the restaurant industry association, told the radio station Franceinfo on Sunday. “For the last three weeks, there haven’t been any here.”

Still, for all the talk of those leaving, there are plenty who have decided to stick around.

Jay Swanson, an American expat and YouTuber, can’t imagine leaving during the Olympics—he secured his tickets to see ping pong and volleyball last year. He’s also less concerned about the crowds and road closures than others, having just put together a series of videos explaining how to navigate Paris during the games.

“It’s been 100 years since the Games came to Paris; when else will we get a chance to host the world like this?” Swanson says. “So many Parisians are leaving and tourism is down, so not only will it be quiet but the only people left will be here for a party.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.