China’s Growth Slows to Three-Decade Low Excluding Pandemic

A festering property-market meltdown offsets much of the benefit of economy’s post pandemic recovery

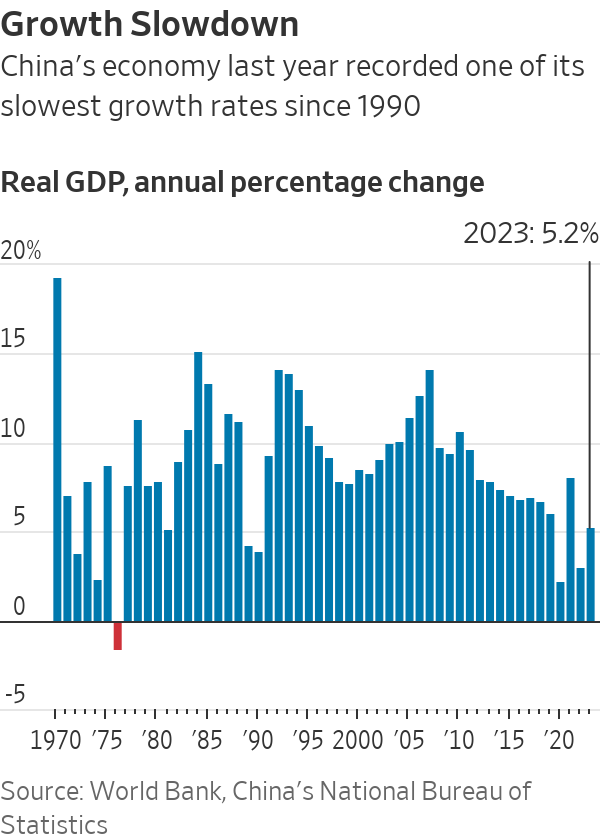

HONG KONG—China’s economic growth rate finished at one of the lowest levels in decades last year, underscoring the heavy toll that a property-sector collapse and weak consumer confidence have taken on the world’s second-largest economy despite the lifting of all Covid-19 restrictions.

Gross domestic product in China expanded 5.2% in the fourth quarter and for the full year in 2023, according to data released by the National Bureau of Statistics on Wednesday. The reading confirmed a number uttered by Premier Li Qiang a day earlier at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland—an unusual disclosure of a high-profile data point by a senior leader before its formal release.

Apart from the three years that China was closed to the outside world during the pandemic, the country’s economy expanded in 2023 at the slowest annual rate since 1990, the year after the political turmoil of the student movement that was crushed around Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in June 1989.

In 2022, China’s economy grew 3%, while 2020—the initial year of Covid-19—saw growth of just 2.2%. This year’s outcome was flattered in part by comparison with the relatively low base of 2022, when harsh pandemic lockdowns swept the nation, crimping growth.

Last year’s 5.2% growth rate managed to top the government’s official target of around 5% growth, following a year of volatility and shifting expectations.

Maintaining growth at a similar pace this year may prove harder, given policymakers’ hesitance so far to launch any big-ticket stimulus packages. Forecasts for China’s growth rate this year among several global investment banks range from 4% to 4.9%. China is expected to announce any formal growth target at an annual legislative session set to take place in March.

In the near term, China has few obvious growth drivers. Export demand is softening as the global economy is projected to slow this year. Chinese families, hit by years of pandemic restrictions and receiving no direct financial support from the government, have turned cautious on spending amid a weak job market. Private businesses have been holding off on new investments while foreign investors are pulling funds out of the country.

The Chinese leadership’s determination to cultivate new engines of growth, in fields such as electric vehicles and renewable energy, is bearing fruit. Still, in the near term, it won’t likely be enough to make up for the shortfalls in job creation and overall growth rate from the rapid decline in its once-mighty real-estate sector.

In the longer run, China faces a daunting list of headwinds, including a population that is rapidly skewing older, high debt levels and a worsening external political environment that has seen relations with the U.S.-led West plummet.

Wednesday’s data release offered fresh signs of the dire state of the country’s demographics. Official statisticians said China’s population shrank by 2.08 million people last year, falling to 1.410 billion, after declining in 2022 for the first time in decades.

Economists are concerned that China may be falling into a vicious cycle in which falling prices and weak demand reinforce one another, as they did in Japan in the 1990s. Chinese policymakers’ reluctance to stimulate more forcefully has confounded many economists, though others have pointed to leader Xi Jinping’s ideologically-rooted reluctance to shower the economy with government money.

Instead, Chinese authorities have unleashed a barrage of smaller-bore measures, such as trimming key interest rates, cutting mortgage costs for home buyers and prodding banks to lend more to distressed property developers. Collectively, though, those measures have done little to reverse downward pressure on the economy. The government said in the fall that it would issue $137 billion in government debt, the biggest stimulus measure it has undertaken so far—though still not enough to reverse the downward momentum, economists say.

“I wonder if they are not realising how big the risk is if deflation pressure becomes entrenched,” says Alicia García-Herrero, chief Asia economist at investment bank Natixis.

Chinese stocks fell after the data was released. The CSI 300 index was down 1.4%, putting it on course to close at its lowest level in almost five years. Hong Kong’s Hang Seng Index, which includes the shares of many Chinese companies, was around 3.7% lower.

The country’s stock market is now in a multi-year slump, with foreign portfolio managers fleeing and individual investors in the country switching to safer assets. The poor state of the economy is a constant concern.

The past year had started off with a sense of buoyant optimism, as the abandonment of three years of stifling Covid-related restrictions spurred a revival of spending by consumers.

But the reopening momentum quickly lost steam after the first quarter, as global demand for Chinese-made exports—a key pillar of China’s economy throughout the pandemic years—began to wane. Persistent high youth unemployment and weak wage growth further weighed on average households’ fragile confidence.

In the fall, factory activity weakened again and consumer prices dropped into deflationary territory.

Throughout it all, a years long decline in Chinese home prices showed no sign of abating, further depriving revenue for debt-laden developers and eroding homeowners’ wealth and sense of financial security.

Looking ahead, economists have called on leaders in Beijing to step in forcefully to stabilise home prices and contain the risk of widening defaults among property developers.

“The key thing to watch in 2024 is if and when the central government would step in and take the main responsibility to stop the contagion,” said Larry Hu, chief China economist at Macquarie Group.

Whether Beijing can revive consumer confidence will be another key metric to watch this year.

In the central Chinese city of Wuhan, Bella Liu, a 32-year-old employee of a telecommunications firm, remembered 2023 as a year marked by plunging profits and frequent layoffs in her industry. After suffering a nearly 20% loss from her mutual fund investments, she is now parking more of her money in time deposits at her bank.

“In an era of slowing economic growth, I just feel lucky that I have a job,” Liu said.

Full-year economic data released by China on Wednesday showed retail sales, a key gauge of consumer spending, gained 7.4% in December and rose 7.2% for the full year compared with the respective year-earlier periods. Retail sales had fallen 0.2% for the full year in 2022.

The new data suggest that the economy is again beginning to rely more on domestic demand after counting on exports as the main pillar of growth during the pandemic years. Consumption was the largest contributor to overall growth in 2023. Still, it is unclear how much of a role it will play in driving the Chinese economy this year, in part because the release of pent-up pandemic demand has largely run its course, according to economists from Nomura.

Investment was also lacklustre in 2023. Fixed-asset investment growth slowed last year, rising 3.0% for the full year compared with a 5.1% expansion in 2022. Private-sector investment, too, remained weak, falling 0.4% in 2023 compared with a year earlier as policy uncertainty spooked entrepreneurs. Private-sector investment had risen 0.9% in 2022.

Over the course of 2023, Beijing rolled out measures aimed at reining in the technology sector, including the video game industry, while warning about foreign espionage and detaining employees of foreign firms operating in China.

Readings of the property sector offered more reason for caution. New home prices in China’s 70 major cities dropped at a faster clip toward the end of 2023.

Average new home prices in December fell 0.45% from November, and 0.89% when from a year earlier, according to calculations by The Wall Street Journal based on data released by the statistics bureau. The pace of both declines was worse than in November.

For the full year, property investment fell 9.6%, while new construction starts dropped 20.4% and home sales by value declined 6.0%.

The surveyed urban unemployment edged up to 5.1% in December, from 5% in November. Economists have cast doubt on the accuracy of official statistics on joblessness in large part because the survey leaves out the country’s nearly 300 million migrant workers.

In a surprise move, China released a revised youth unemployment figure for the first time since July, when it abruptly suspended the publication of the data series amid a run of fresh record-high readings up to 21.3%.

On Wednesday, China’s statistics bureau said that it would publish a new urban youth unemployment figure each month for people age 16 to 24 that excludes students. The reading was 14.9% in December.

The statistics bureau said that the new methodology offers a more refined and comprehensive picture that would “better reflect the employment situation” by only including graduates who were looking for work.

Still, the economy had pockets of strength, especially in dominating the global supply chain for renewable energy products such as solar panels and electric vehicles. Growth in industrial production rebounded to 4.6%, accelerating from a 3.6% increase the year before, Wednesday’s data show.

—Grace Zhu and Xiao Xiao in Beijing contributed to this article.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Ahead of the Games, a breakdown of the city’s most desirable places to live

PARIS —Paris has long been a byword for luxurious living. The traditional components of the upscale home, from parquet floors to elaborate moldings, have their origins here. Yet settling down in just the right address in this low-rise, high-density city may be the greatest luxury of all.

Tradition reigns supreme in Paris real estate, where certain conditions seem set in stone—the western half of the city, on either side of the Seine, has long been more expensive than the east. But in the fashion world’s capital, parts of the housing market are also subject to shifting fads. In the trendy, hilly northeast, a roving cool factor can send prices in this year’s hip neighborhood rising, while last year’s might seem like a sudden bargain.

This week, with the opening of the Olympic Games and the eyes of the world turned toward Paris, The Wall Street Journal looks at the most expensive and desirable areas in the City of Light.

The Most Expensive Arrondissement: the 6th

Known for historic architecture, elegant apartment houses and bohemian street cred, the 6th Arrondissement is Paris’s answer to Manhattan’s West Village. Like its New York counterpart, the 6th’s starving-artist days are long behind it. But the charm that first wooed notable residents like Gertrude Stein and Jean-Paul Sartre is still largely intact, attracting high-minded tourists and deep-pocketed homeowners who can afford its once-edgy, now serene atmosphere.

Le Breton George V Notaires, a Paris notary with an international clientele, says the 6th consistently holds the title of most expensive arrondissement among Paris’s 20 administrative districts, and 2023 was no exception. Last year, average home prices reached $1,428 a square foot—almost 30% higher than the Paris average of $1,100 a square foot.

According to Meilleurs Agents, the Paris real estate appraisal company, the 6th is also home to three of the city’s five most expensive streets. Rue de Furstemberg, a secluded loop between Boulevard Saint-Germain and the Seine, comes in on top, with average prices of $2,454 a square foot as of March 2024.

For more than two decades, Kyle Branum, a 51-year-old attorney, and Kimberly Branum, a 60-year-old retired CEO, have been regular visitors to Paris, opting for apartment rentals and ultimately an ownership interest in an apartment in the city’s 7th Arrondissement, a sedate Left Bank district known for its discreet atmosphere and plutocratic residents.

“The 7th was the only place we stayed,” says Kimberly, “but we spent most of our time in the 6th.”

In 2022, inspired by the strength of the dollar, the Branums decided to fulfil a longstanding dream of buying in Paris. Working with Paris Property Group, they opted for a 1,465-square-foot, three-bedroom in a building dating to the 17th century on a side street in the 6th Arrondissement. They paid $2.7 million for the unit and then spent just over $1 million on the renovation, working with Franco-American visual artist Monte Laster, who also does interiors.

The couple, who live in Santa Barbara, Calif., plan to spend about three months a year in Paris, hosting children and grandchildren, and cooking after forays to local food markets. Their new kitchen, which includes a French stove from luxury appliance brand Lacanche, is Kimberly’s favourite room, she says.

Another American, investor Ashley Maddox, 49, is also considering relocating.

In 2012, the longtime Paris resident bought a dingy, overstuffed 1,765-square-foot apartment in the 6th and started from scratch. She paid $2.5 million and undertook a gut renovation and building improvements for about $800,000. A centrepiece of the home now is the one-time salon, which was turned into an open-plan kitchen and dining area where Maddox and her three children tend to hang out, American-style. Just outside her door are some of the city’s best-known bakeries and cheesemongers, and she is a short walk from the Jardin du Luxembourg, the Left Bank’s premier green space.

“A lot of the majesty of the city is accessible from here,” she says. “It’s so central, it’s bananas.” Now that two of her children are going away to school, she has listed the four-bedroom apartment with Varenne for $5 million.

The Most Expensive Neighbourhoods: Notre-Dame and Invalides

Garrow Kedigian is moving up in the world of Parisian real estate by heading south of the Seine.

During the pandemic, the Canada-born, New York-based interior designer reassessed his life, he says, and decided “I’m not going to wait any longer to have a pied-à-terre in Paris.”

He originally selected a 1,130-square-foot one-bedroom in the trendy 9th Arrondissement, an up-and-coming Right Bank district just below Montmartre. But he soon realised it was too small for his extended stays, not to mention hosting guests from out of town.

After paying about $1.6 million in 2022 and then investing about $55,000 in new decor, he put the unit up for sale in early 2024 and went house-shopping a second time. He ended up in the Invalides quarter of the 7th Arrondissement in the shadow of one Paris’s signature monuments, the golden-domed Hôtel des Invalides, which dates to the 17th century and is fronted by a grand esplanade.

His new neighbourhood vies for Paris’s most expensive with the Notre-Dame quarter in the 4th Arrondissement, centred on a few islands in the Seine behind its namesake cathedral. According to Le Breton, home prices in the Notre-Dame neighbourhood were $1,818 a square foot in 2023, followed by $1,568 a square foot in Invalides.

After breaking even on his Right Bank one-bedroom, Kedigian paid $2.4 million for his new 1,450-square-foot two-bedroom in a late 19th-century building. It has southern exposures, rounded living-room windows and “gorgeous floors,” he says. Kedigian, who bought the new flat through Junot Fine Properties/Knight Frank, plans to spend up to $435,000 on a renovation that will involve restoring the original 12-foot ceiling height in many of the rooms, as well as rescuing the ceilings’ elaborate stucco detailing. He expects to finish in 2025.

Over in the Notre-Dame neighbourhood, Belles demeures de France/Christie’s recently sold a 2,370-square-foot, four-bedroom home for close to the asking price of about $8.6 million, or about $3,630 a square foot. Listing agent Marie-Hélène Lundgreen says this places the unit near the very top of Paris luxury real estate, where prime homes typically sell between $2,530 and $4,040 a square foot.

The Most Expensive Suburb: Neuilly-sur-Seine

The Boulevard Périphérique, the 22-mile ring road that surrounds Paris and its 20 arrondissements, was once a line in the sand for Parisians, who regarded the French capital’s numerous suburbs as something to drive through on their way to and from vacation. The past few decades have seen waves of gentrification beyond the city’s borders, upgrading humble or industrial districts to the north and east into prime residential areas. And it has turned Neuilly-sur-Seine, just northwest of the city, into a luxury compound of first resort.

In 2023, Neuilly’s average home price of $1,092 a square foot made the leafy, stately community Paris’s most expensive suburb.

Longtime residents, Alain and Michèle Bigio, decided this year is the right time to list their 7,730-square-foot, four-bedroom townhouse on a gated Neuilly street.

The couple, now in their mid 70s, completed the home in 1990, two years after they purchased a small parcel of garden from the owners next door for an undisclosed amount. Having relocated from a white-marble château outside Paris, the couple echoed their previous home by using white- and cream-coloured stone in the new four-story build. The Bigios, who will relocate just back over the border in the 16th Arrondissement, have listed the property with Emile Garcin Propriétés for $14.7 million.

The couple raised two adult children here and undertook upgrades in their empty-nester years—most recently, an indoor pool in the basement and a new elevator.

The cool, pale interiors give way to dark and sardonic images in the former staff’s quarters in the basement where Alain works on his hobby—surreal and satirical paintings, whose risqué content means that his wife prefers they stay downstairs. “I’m not a painter,” he says. “But I paint.”

The Trendiest Arrondissement: the 9th

French interior designer Julie Hamon is theatre royalty. Her grandfather was playwright Jean Anouilh, a giant of 20th-century French literature, and her sister is actress Gwendoline Hamon. The 52-year-old, who divides her time between Paris and the U.K., still remembers when the city’s 9th Arrondissement, where she and her husband bought their 1,885-square-foot duplex in 2017, was a place to have fun rather than put down roots. Now, the 9th is the place to do both.

The 9th, a largely 19th-century district, is Paris at its most urban. But what it lacks in parks and other green spaces, it makes up with nightlife and a bustling street life. Among Paris’s gentrifying districts, which have been transformed since 2000 from near-slums to the brink of luxury, the 9th has emerged as the clear winner. According to Le Breton, average 2023 home prices here were $1,062 a square foot, while its nearest competitors for the cool crown, the 10th and the 11th, have yet to break $1,011 a square foot.

A co-principal in the Bobo Design Studio, Hamon—whose gut renovation includes a dramatic skylight, a home cinema and air conditioning—still seems surprised at how far her arrondissement has come. “The 9th used to be well known for all the theatres, nightclubs and strip clubs,” she says. “But it was never a place where you wanted to live—now it’s the place to be.”

With their youngest child about to go to college, she and her husband, 52-year-old entrepreneur Guillaume Clignet, decided to list their Paris home for $3.45 million and live in London full-time. Propriétés Parisiennes/Sotheby’s is handling the listing, which has just gone into contract after about six months on the market.

The 9th’s music venues were a draw for 44-year-old American musician and piano dealer, Ronen Segev, who divides his time between Miami and a 1,725-square-foot, two-bedroom in the lower reaches of the arrondissement. Aided by Paris Property Group, Segev purchased the apartment at auction during the pandemic, sight unseen, for $1.69 million. He spent $270,000 on a renovation, knocking down a wall to make a larger salon suitable for home concerts.

During the Olympics, Segev is renting out the space for about $22,850 a week to attendees of the Games. Otherwise, he prefers longer-term sublets to visiting musicians for $32,700 a month.

Most Exclusive Address: Avenue Junot

Hidden in the hilly expanses of the 18th Arrondissement lies a legendary street that, for those in the know, is the city’s most exclusive address. Avenue Junot, a bucolic tree-lined lane, is a fairy-tale version of the city, separate from the gritty bustle that surrounds it.

Homes here rarely come up for sale, and, when they do, they tend to be off-market, or sold before they can be listed. Martine Kuperfis—whose Paris-based Junot Group real-estate company is named for the street—says the most expensive units here are penthouses with views over the whole of the city.

In 2021, her agency sold a 3,230-square-foot triplex apartment, with a 1,400-square-foot terrace, for $8.5 million. At about $2,630 a square foot, that is three times the current average price in the whole of the 18th.

Among its current Junot listings is a 1930s 1,220-square-foot townhouse on the avenue’s cobblestone extension, with an asking price of $2.8 million.

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.