How Reflective Paint Brings Down Scorching City Temperatures

Communities fight urban heat islands with technologies shielding roofs and pavement

Cities across the U.S. have found relief from this summer’s record-setting heat with the help of technologies that shield roofs, pavement and other surfaces from the sun’s scorching rays.

Some of these technologies have been around for more than a decade but are experiencing greater demand as global temperatures rise. Washington, D.C., for example, has built more than 3,200 green roofs covering 9 million square feet—up from about 300,000 square feet in 2006, according to federal and city officials.

Other technologies, such as super-reflective coatings for pavement, streets and windows, are just now becoming effective and affordable enough for widespread use.

The Los Angeles neighbourhood of Pacoima, a densely packed location sandwiched between freeways and an industrial area, has created a partnership with GAF, a New Jersey-based roofing manufacturer, to paint a basketball court, local park and neighbourhood streets with a reflective coating.

“There’s a lot of asphalt and lack of investment for tree canopies,” said Melanie Paola Torres, 24 years old, a community organiser with the group Pacoima Beautiful. “Given the fact that we are in an industrial zone, that contributes to the urban heat-island effect.”

The reflective coating has reduced air temperatures in the test area at 6 feet above ground by 3.5 degrees Fahrenheit during extreme heat days, and surface temperatures by 10 degrees, according to Jeff Terry, GAF’s vice president of corporate social responsibility and sustainability.

Sweltering conditions are worse in urban heat islands, which can be 10 degrees hotter than surrounding suburbs and occur as buildings, roads and other infrastructure absorb and re-emit the sun’s energy.

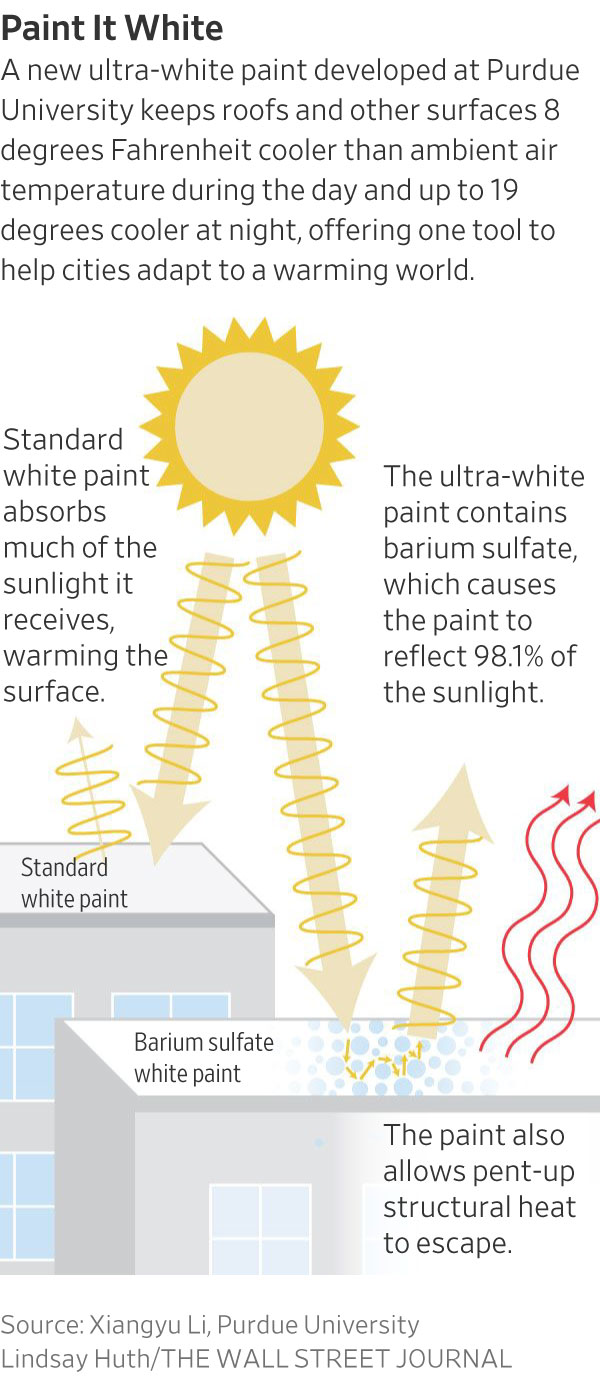

Cooling technologies mitigate this. Green roofs absorb heat before it penetrates the buildings beneath. Super-reflective coatings reflect the sun’s visible light and invisible infrared radiation away from surfaces to keep them cooler. And an ultra-white paint developed at Purdue University promises even more protection, although the product isn’t commercially available yet. Each strategy helps reduce energy use.

“The important thing is to help people cool their homes and workplaces affordably,” said Jane Gilbert, chief heat officer for Miami-Dade County, which experienced a record 46 straight days of a 100-degree-plus heat index this summer. “The more efficient we can make both the buildings and the AC systems themselves, the less we’re contributing both to greenhouse gases and also waste heat that goes to our urban heat islands.”

Miami is one of the most vulnerable cities to the urban heat-island effect, along with San Francisco, New York, Chicago and Seattle, according to an analysis by Climate Central, a New Jersey-based nonprofit that researches the effects of climate change. Its analysis found that 41 million people living in 44 cities face an urban heat-island effect of at least 8 degrees. Nine U.S. cities had at least one million people exposed to urban heat of 8 degrees or higher because of the local built environment.

To fight the heat, some cities are leveraging federal money and other incentives to persuade local builders to turn office buildings greener and cooler.

In Miami-Dade County, officials used federal funds to outfit 1,700 public housing units with new low-energy air-conditioning units. Local officials also offered a successful amendment to the Florida state building code requiring cool reflective roofs on all new commercial buildings beginning in 2024, and enrolled 150 structures in a voluntary energy-audit program to track improvements to cut energy use and keep temperatures down.

New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Toronto and other cities are pushing green roofs with tax breaks and other incentives in an effort to lower energy bills and reduce ambient temperatures, according to Steven Peck, president of Green Roofs for Healthy Cities, a Toronto-based green-roof and -wall industry association. Peck said green roofs can be 30 to 40 degrees cooler than a similar-size blacktop roof, while also cutting waste heat from air-conditioning units.

In the Los Angeles neighbourhood of Pacoima, Torres says residents tell her the streets and playgrounds feel cooler since the reflective coating was completed in August 2022.

“The number-one thing that always comes up is the heat waves when you’re looking down the street,” Torres said. “They don’t see those anymore.”

The next step is to install reflective roofing material on a handful of homes as part of the neighbourhood cooling effort. “We want to keep stacking the solutions to overall create a cool community with multiple strategies,” Torres said.

Altering the urban landscape to adapt to extreme heat requires money and technical know-how, according to city leaders and academic experts. But they also acknowledge the need to keep people safe as global temperatures rise.

“Any one solution is not going to necessarily be able to address the entire problem, but by systematically applying solutions that work in each individual location, we can make a dent in the urban heat-island effect,” said David Sailor, professor of geographical sciences and urban planning at Arizona State University.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

The remote northern island wants more visitors: ‘It’s the rumbling before the herd is coming,’ one hotel manager says

As European hot spots become overcrowded , travellers are digging deeper to find those less-populated but still brag-worthy locations. Greenland, moving up the list, is bracing for its new popularity.

Aria Varasteh has been to 69 countries, including almost all of Europe. He now wants to visit more remote places and avoid spots swarmed by tourists—starting with Greenland.

“I want a taste of something different,” said the 34-year-old founder of a consulting firm serving clients in the Washington, D.C., area.

He originally planned to go to Nuuk, the island’s capital, this fall via out-of-the-way connections, given there wasn’t a nonstop flight from the U.S. But this month United Airlines announced a nonstop, four-hour flight from Newark Liberty International Airport in New Jersey to Nuuk. The route, beginning next summer, is a first for a U.S. airline, according to Greenland tourism officials.

It marks a significant milestone in the territory’s push for more international visitors. Airlines ran flights with a combined 55,000 seats to Greenland from April to August of this year, says Jens Lauridsen, chief executive officer of Greenland Airports. That figure will nearly double next year in the same period, he says, to about 105,000 seats.

The possible coming surge of travellers also presents a challenge for a vast island of 56,000 people as nearby destinations from Iceland to Spain grapple with the consequences of over tourism.

Greenlandic officials say they have watched closely and made deliberate efforts to slowly scale up their plans for visitors. An investment north of $700 million will yield three new airports, the first of which will open next month in Nuuk.

“It’s the rumbling before the herd is coming,” says Mads Mitchell, general manager of Hotel Nordbo, a 67-room property in Nuuk. The owner of his property is considering adding 50 more rooms to meet demand in the coming years.

Mitchell has recently met with travel agents from Brooklyn, N.Y., South Korea and China. He says he welcomes new tourists, but fears tourism will grow too quickly.

“Like in Barcelona, you get tired of tourists, because it’s too much and it pushes out the locals, that is my concern,” he says. “So it’s finding this balance of like showing the love for Greenland and showing the amazing possibilities, but not getting too much too fast.”

Greenland’s buildup

Greenland is an autonomous territory of Denmark more than three times the size of Texas. Tourists travel by boat or small aircraft when venturing to different regions—virtually no roads connect towns or settlements.

Greenland decided to invest in airport infrastructure in 2018 as part of an effort to expand tourism and its role in the economy, which is largely dependent on fishing and subsidies from Denmark. In the coming years, airports in Ilulissat and Qaqortoq, areas known for their scenic fjords, will open.

One narrow-body flight, like what United plans, will generate $200,000 in spending, including hotels, tours and other purchases, Lauridsen says. He calls it a “very significant economic impact.”

In 2023, foreign tourism brought a total of over $270 million to Greenland’s economy, according to Visit Greenland, the tourism and marketing arm owned by the government. Expedition cruises visit the territory, as well as adventure tours.

United will fly twice weekly to Nuuk on its 737 MAX 8, which will seat 166 passengers, starting in June .

“We look for new destinations, we look for hot destinations and destinations, most importantly, we can make money in,” Andrew Nocella , United’s chief commercial officer, said in the company’s earnings call earlier in October.

On the runway

Greenland has looked to nearby Iceland to learn from its experiences with tourism, says Air Greenland Group CEO Jacob Nitter Sørensen. Tiny Iceland still has about seven times the population of its western neighbour.

Nuuk’s new airport will become the new trans-Atlantic hub for Air Greenland, the national carrier. It flies to 14 airports and 46 heliports across the territory.

“Of course, there are discussions about avoiding mass tourism. But right now, I think there is a natural limit in terms of the receiving capacity,” Nitter says.

Air Greenland doesn’t fly nonstop from the U.S. because there isn’t currently enough space to accommodate all travellers in hotels, Nitter says. Air Greenland is building a new hotel in Ilulissat to increase capacity when the airport opens.

Nuuk has just over 550 hotel rooms, according to government documents. A tourism analysis published by Visit Greenland predicts there could be a shortage in rooms beginning in 2027. Most U.S. visitors will stay four to 10 nights, according to traveler sentiment data from Visit Greenland.

As travel picks up, visitors should expect more changes. Officials expect to pass new legislation that would further regulate tourism in time for the 2025 season. Rules on zoning would give local communities the power to limit tourism when needed, says Naaja H. Nathanielsen, minister for business, trade, raw materials, justice and gender equality.

Areas in a so-called red zone would ban tour operators. In northern Greenland, traditional hunting takes place at certain times of year and requires silence, which doesn’t work with cruise ships coming in, Nathanielsen says.

Part of the proposal would require tour operators to be locally based to ensure they pay taxes in Greenland and so that tourists receive local knowledge of the culture. Nathanielsen also plans to introduce a proposal to govern cruise tourism to ensure more travelers stay and eat locally, rather than just walk around for a few hours and grab a cup of coffee, she says.

Public sentiment has remained in favour of tourism as visitor arrivals have increased, Nathanielsen says.

—Roshan Fernandez contributed to this article.

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.