The Pain of the Never-Ending Work Check-In

Meeting burnout got worse in the pandemic; hybrid schedules could make things even messier

Brenda Fernandez has tried blocking off time on her calendar. She’s tried to keep conversations focused. She still can’t escape them.

“Everything becomes a meeting,” the 29-year-old Miami copywriter told me. Her overwhelming feeling? “This could have been an email.”

Then she excused herself to hop on a 7 p.m. call.

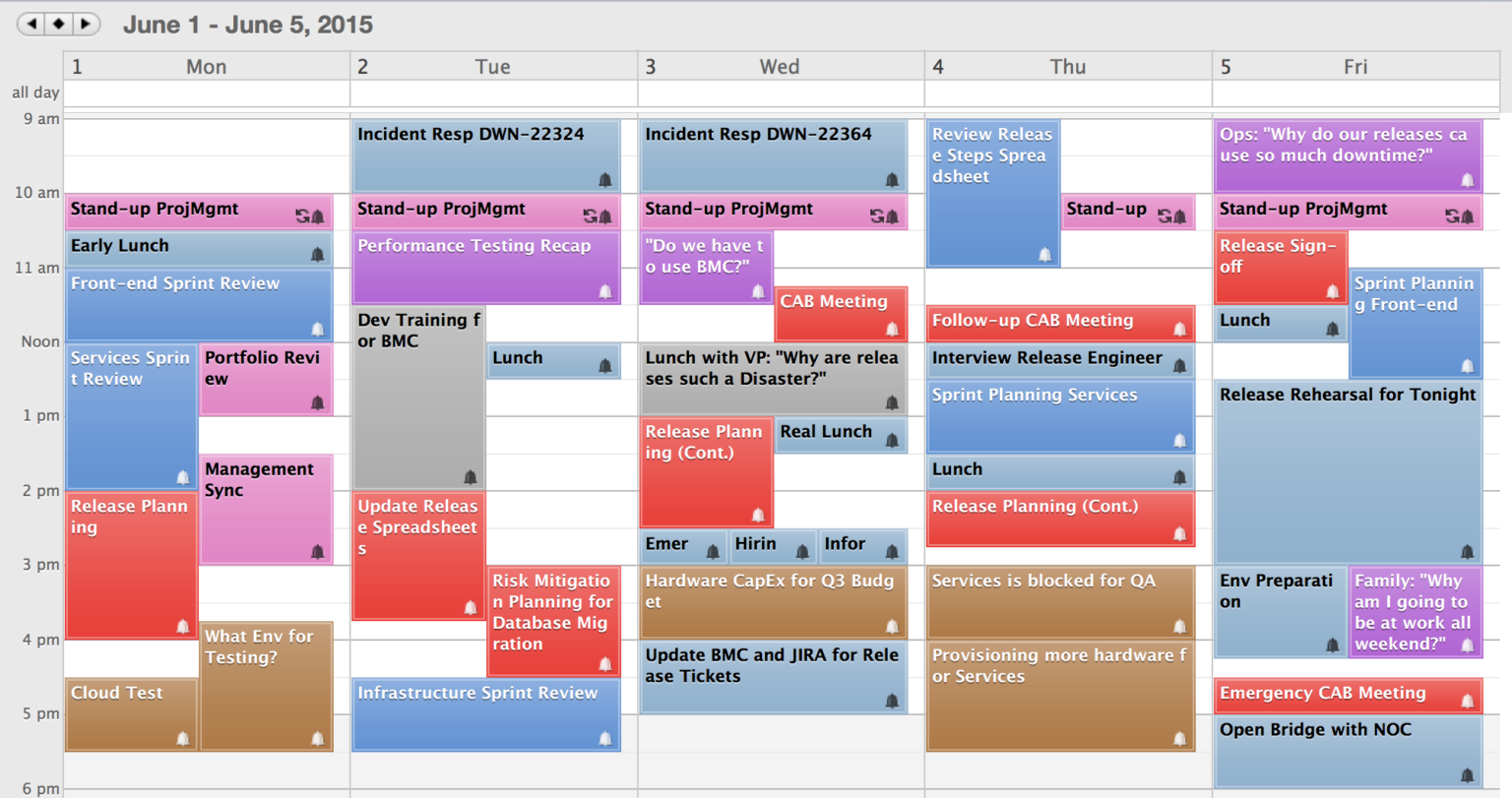

We are deep in the age of the never-ending check-in. Meetings have gotten shorter during the pandemic, according to researchers, with one paper finding the average length dropped 20% in late 2020.

But meetings are multiplying. There’s the 25-minute client touch-base, the general life catch-up with your manager, the bite-size performance feedback session, the meeting to prep for the meeting.

“It just never ends,” Ms. Fernandez says.

We were already on the road to meeting burnout before the pandemic. A shift from hierarchical organisations to de-layered, matrixed ones means more bosses and teams to coordinate with. Increasingly global business means invites for times when we’d normally be in bed. Caroline Kim Oh, a leadership coach based near New York City, says that in recent years, many of her clients have started feeling like meetings are just something that happens to them.

“You have no control over your workday,” she says. “They’re just popping up.”

Working from home and living through a crisis seems to have made it worse. In an April survey from meeting scheduling tool Doodle, 69% of 1,000 full-time remote workers said their meetings had increased since the pandemic started, with 56% reporting that their swamped calendars were hurting their job performance.

Constant check-ins have become some bosses’ version of micromanaging, a way to keep tabs on workers they don’t trust. Coordination that used to happen by swivelling your chair or walking across the hall now requires extra formality and time for everyone still spread out across home offices. Plus, there’s the sense that empathetic leaders should stay in touch during moments of transition, whether that’s as the world was shutting down last year or as we head back to headquarters now.

The message to managers is often, “Hey, check in with your employees. See if they’re OK. Care more,” says Ms. Kim Oh, the executive coach. Sometimes caring more means saving a worker from one more Zoom, she adds.

What happens next? If we all go back to work five days a week, we might return to those efficient, in-person check-ins, says Raffaella Sadun, a Harvard Business School professor who has studied meeting loads before and during the pandemic. But organisations testing a hybrid set-up should brace for a mess.

There are now two kinds of interactions to manage, Dr. Sadun says. “One is at the water cooler, one is on Zoom.” If you make a decision with the colleague who sits one desk over, you still need to dial up the teammate who spends Tuesdays at home to make sure she’s on board. Suddenly, all Zoom all the time doesn’t seem so bad.

Nonetheless, many employees are optimistic that things will get better. In the Doodle survey, 70% of respondents said they hope to have fewer meetings once they head back to the office. Angela Nguyen, an independent healthcare consultant in Boston, predicts workers will return to the good old days of back-to-back meetings, as opposed to the double- and triple-booked schedules she sees now.

“It’s not sustainable,” she says. She has watched clients attempt to divide and conquer, hopping on for 15-minute cameos or dispatching various team members to different video calls. Then they sync up after—with another meeting.

Did we all just get used to having our professional contacts a click away for all these months, without travel time or personal plans as a natural boundary? Does loneliness play a role?

“I wonder if people just want to connect, just to chat, because they don’t have an office to go to,” Ms. Nguyen says.

Overall, employees have been putting in five to eight additional working hours a week during the pandemic, says Rob Cross, a professor of global leadership at Babson College and author of the forthcoming book, “Beyond Collaboration Overload.” More meetings mean more tasks to catch up on at day’s end, when we finally have a minute to take a look at our ballooning to-do lists. Plus, toggling between more, shorter meetings is hugely taxing on our brains.

“They’ve created work that they don’t see,” Dr. Cross says of organizations. “That’s crushing people.”

Becca Apfelstadt’s team at marketing agency Treetree headed back to their Columbus, Ohio, office last month for two half-days a week. The CEO’s verdict on meetings is: They’re no worse than before. Early in the pandemic, workers complained they didn’t have time to grab water or use the bathroom. “It was like, we won’t survive if we can’t figure this out,” she says.

The company moved some communication to messaging services such as Slack, trimmed meetings to 20 or 50 minutes and encouraged walk-and-talk conversations, using AI services to take notes.

The efforts helped, Ms. Apfelstadt says, and so far the shift to hybrid hasn’t created any meeting creep. Still, there have been hiccups. The other week, she spotted three employees crammed onto a couch together, attempting to share one laptop camera for a video conference.

“They just had some tiny person in the middle, and she was just getting smushed any time someone would try to make a point,” Ms. Apfelstadt says. She recommends companies keep the formal meeting schedule light as they transition back and lean into serendipitous conversations around the office.

Still, not everyone is craving those. Seanna Thompson, a physician and administrator with New York’s Mount Sinai Health System, has loved her remote meetings over the last year-plus. The dread comes when she thinks about returning to those ad-hoc, meandering check-ins by the water cooler.

“I’m like, oh God, that just derailed my whole day,” she says. “I don’t think what we were doing before was all that efficient.”

Reprinted by permission of The Wall Street Journal, Copyright 2021 Dow Jones & Company. Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. Original date of publication: July 19, 2021

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

More than one fifth of Australians are cutting back on the number of people they socialise with

Australian social circles are shrinking as more people look for ways to keep a lid on spending, a new survey has found.

New research from Finder found more than one fifth of respondents had dropped a friend or reduced their social circle because they were unable to afford the same levels of social activity. The survey questioned 1,041 people about how increasing concerns about affordability were affecting their social lives. The results showed 6 percent had cut ties with a friend, 16 percent were going out with fewer people and 26 percent were going to fewer events.

Expensive events such as hens’ parties and weddings were among the activities people were looking to avoid, indicating younger people were those most feeling the brunt of cost of living pressures. According to Canstar, the average cost of a wedding in NSW was between $37,108 to $41,245 and marginally lower in Victoria at $36, 358 to $37,430.

But not all age groups are curbing their social circle. While the survey found that 10 percent of Gen Z respondents had cut off a friend, only 2 percent of Baby Boomers had done similar.

Money expert at Finder, Rebecca Pike, said many had no choice but to prioritise necessities like bills over discretionary activities.

“Unfortunately, for some, social activities have become a luxury they can no longer afford,” she said.

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.