Big Oil’s Talent Crisis: High Salaries Are No Longer Enough

Energy companies scramble to attract engineers as young workers fret over climate and job security

Good news from the oil patch: Jobs are plentiful and salaries are soaring.

The bad news is that young people still aren’t interested.

Even as oil-and-gas companies post record profits, the industry is facing a worsening talent drought.

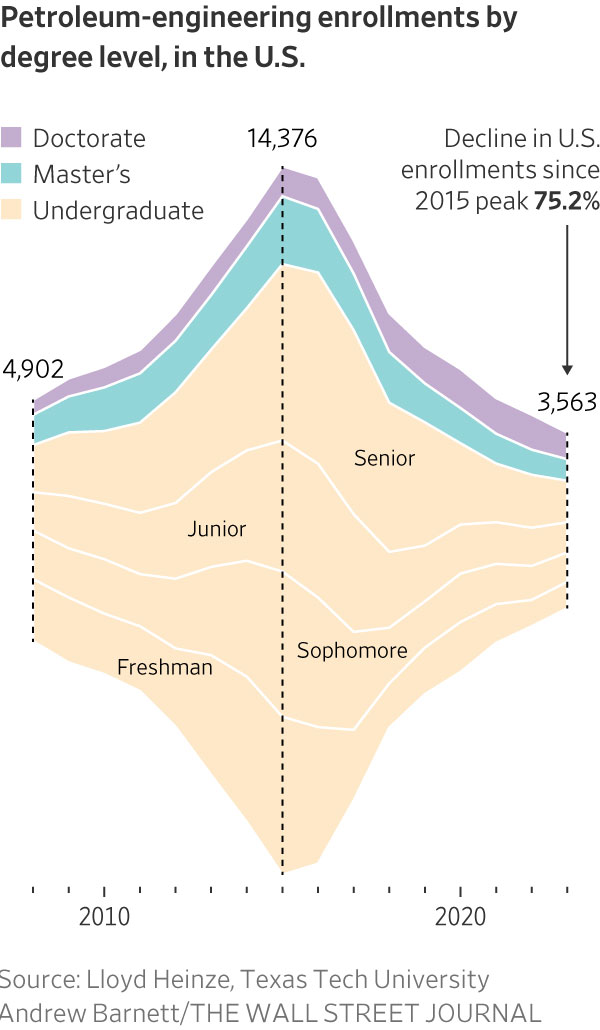

At U.S. colleges, the pool of new entrants for petroleum-engineering programs has shrunk to its smallest size since before the fracking boom began more than a decade ago. European universities, which have historically provided many of the engineers for companies with operations across the Middle East and Asia, are seeing similar trends.

Students and high-skilled young workers are concerned about the industry’s role in climate change, as well as long-term job security given that global economies are transitioning away from fossil fuels to other energy sources, according to executives, analysts and professors.

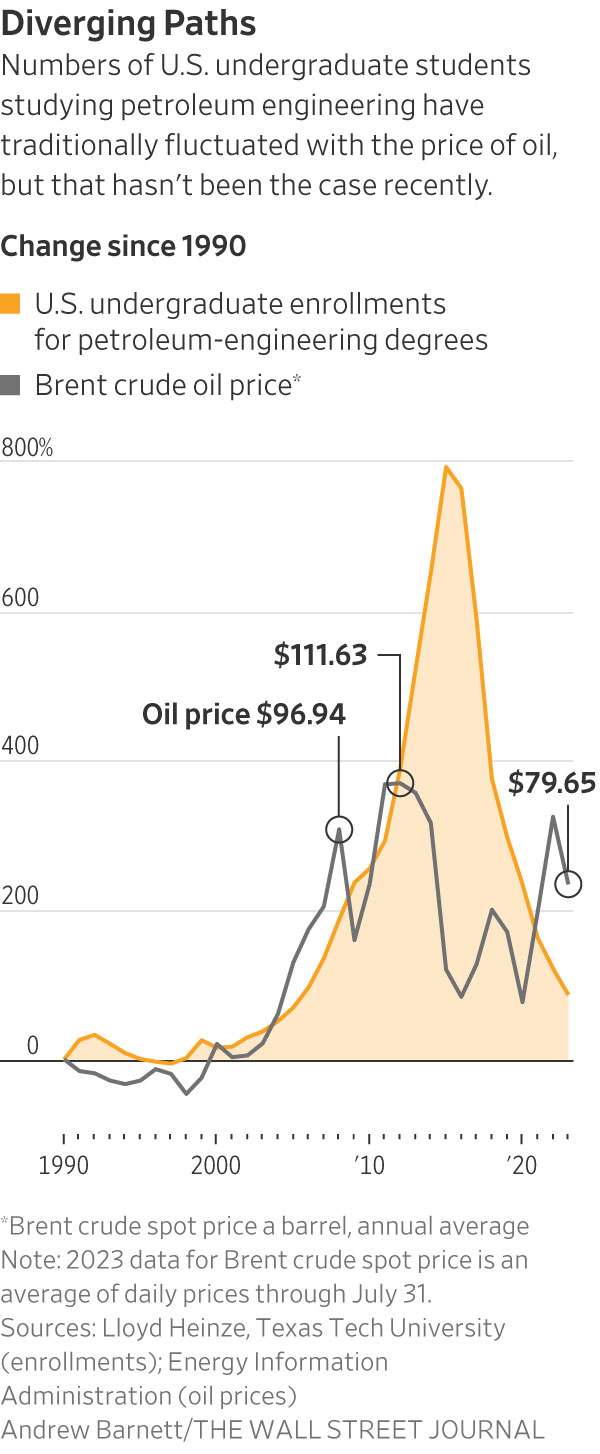

The trend is a stark departure from previous cycles, when the industry’s workforce ebbed and flowed with the rise and fall of oil prices.

Between 2016 and 2021—a period when the Brent crude price nearly doubled—the number of petroleum-engineering graduates more than halved, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

The number of undergraduates pursuing petroleum engineering has dropped 75% since 2014, according to Lloyd Heinze, a Texas Tech University professor.

It is a trend that has continued even as other recent studies have shown that the average graduate earns 40% more than a peer with a computer science degree.

That puts students, including Hayden Gregg, in high demand.

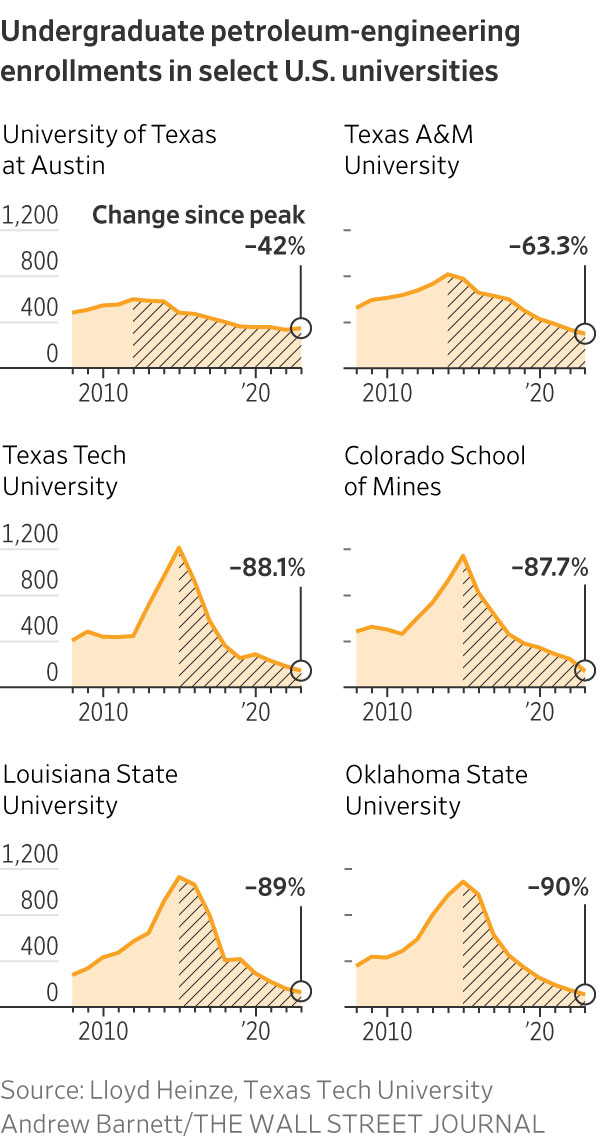

The 21-year-old Kansas City, Mo., native is studying petroleum engineering at Colorado School of Mines. His graduating class of 36 students is down from around 200 in the years before oil prices collapsed in the mid-2010s, according to a college official.

“People are concerned they won’t have a job in 10 to 20 years,” said Gregg.

Encouraged by his roommates and a visit to the oil-and-gas heartland of Texas, he became convinced that the industry offers a range of engineering possibilities as it transitions to a broader mix of energy sources.

“Even if oil and gas is going away, I can deploy my skills in other engineering fields,” he said.

Jennifer Miskimins, head of the petroleum engineering department at Colorado School of Mines, said Gregg’s graduating class is benefiting from a pickup in oil-industry hiring and many have gotten good internships. “They’re a hot commodity,” she said. “I think this class is going to be sitting pretty.”

Oil-and-gas companies are pouring money into fellowships and other programs designed to cultivate a new generation of talent. Much of the focus is on white-collar careers that tend to attract college graduates, but the trend is broadly true among the industry’s blue-collar workers as well.

A big part of the pitch is that the industry is increasingly dynamic and creative, requiring employees who can run carbon capture, hydrogen and geothermal projects, said Barbara Burger, who served in several leadership roles at Chevron and is now a senior adviser at investment bank Lazard.

Part of the challenge, she said, is that there are more startups and fast-growing companies in those fields that don’t carry the same baggage as the giants that earn most of their profits from fossil fuels.

“There’s competition in a way that probably wasn’t there 15 years ago,” she said.

Burger recently attended an event hosted by Fervo Energy, a startup that uses the shale boom’s horizontal drilling and fracking techniques to develop geothermal wells for electricity generation. Around 60% of Fervo’s employees previously worked at oil-and-gas outfits, the company said.

To attract workers, she said, oil-and-gas companies need to better articulate their energy transition strategies, including efforts to carve out new businesses or curb emissions.

“That’s a hook for employees—current and future,” Burger said. “They want to know there’s a future in the actual companies, the industries and the skill sets they have.”

The talent shortage represents a long-term problem at a moment when energy security—largely dependent on fossil fuels for the foreseeable future—is increasingly a global priority. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last year, Europe has become desperate for new supplies of oil and gas, though countries around the world are trying to keep fuel affordable.

Darian Kane-Stolz said that growing up in New York, she was always concerned with climate change. She taught neighbours how to recycle.

When Kane-Stolz, 25, enrolled at the University of Texas at Austin seven years ago, she felt that joining the petroleum-engineering program was consistent with her desire to have a positive impact on the planet.

Now a BP engineer bringing wells online in the Gulf of Mexico, she said the attitude toward the industry has drastically shifted within her cohort. Before she goes out with friends, she sometimes prepares talking points in case someone attacks the industry.

“There’s definitely a negative perception out there,” said Kane-Stolz.

BP this year launched a new $4 million fellowship program with U.S. universities to provide students with exposure to the energy industry. It also said last year that it planned to double the size of its apprenticeship program to 2,000 people this decade.

“To achieve our goal of reimagining energy, we need the brightest talent,” said a BP spokesperson.

Meanwhile, Kane-Stolz’s alma mater, the University of Texas, is working on adding a new master’s degree without the word “petroleum” to capture a broader group of students who still want to work in energy-related engineering, said Jon E. Olson, the department chair of petroleum and geoscience at UT.

Other universities are ending their petroleum engineering degrees or rebranding them. Imperial College London—formerly housing the Royal School of Mines—shut its program last year and replaced it with one in geo-energy with machine learning and data science.

Analysts and company officials say a steady flow of talent is critical to company efforts to build out infrastructure needed to curb emissions and develop clean-energy and low-carbon businesses.

“One of the scarcest resources at the moment seems to be people,” said Aslak Hellestø, a business adviser for Northern Lights, a carbon capture and storage project off the coast of Norway operated by European energy companies Equinor, Shell and TotalEnergies.

“This is groundbreaking technology and we cannot afford to try and fail,” he said. “We need young people with new ideas and bright minds to make it right the first time.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

As Paris makes its final preparations for the Olympic games, its residents are busy with their own—packing their suitcases, confirming their reservations, and getting out of town.

Worried about the hordes of crowds and overall chaos the Olympics could bring, Parisians are fleeing the city in droves and inundating resort cities around the country. Hotels and holiday rentals in some of France’s most popular vacation destinations—from the French Riviera in the south to the beaches of Normandy in the north—say they are expecting massive crowds this year in advance of the Olympics. The games will run from July 26-Aug. 1.

“It’s already a major holiday season for us, and beyond that, we have the Olympics,” says Stéphane Personeni, general manager of the Lily of the Valley hotel in Saint Tropez. “People began booking early this year.”

Personeni’s hotel typically has no issues filling its rooms each summer—by May of each year, the luxury hotel typically finds itself completely booked out for the months of July and August. But this year, the 53-room hotel began filling up for summer reservations in February.

“We told our regular guests that everything—hotels, apartments, villas—are going to be hard to find this summer,” Personeni says. His neighbours around Saint Tropez say they’re similarly booked up.

As of March, the online marketplace Gens de Confiance (“Trusted People”), saw a 50% increase in reservations from Parisians seeking vacation rentals outside the capital during the Olympics.

Already, August is a popular vacation time for the French. With a minimum of five weeks of vacation mandated by law, many decide to take the entire month off, renting out villas in beachside destinations for longer periods.

But beyond the typical August travel, the Olympics are having a real impact, says Bertille Marchal, a spokesperson for Gens de Confiance.

“We’ve seen nearly three times more reservations for the dates of the Olympics than the following two weeks,” Marchal says. “The increase is definitely linked to the Olympic Games.”

Getty Images

According to the site, the most sought-out vacation destinations are Morbihan and Loire-Atlantique, a seaside region in the northwest; le Var, a coastal area within the southeast of France along the Côte d’Azur; and the island of Corsica in the Mediterranean.

Meanwhile, the Olympics haven’t necessarily been a boon to foreign tourism in the country. Many tourists who might have otherwise come to France are avoiding it this year in favour of other European capitals. In Paris, demand for stays at high-end hotels has collapsed, with bookings down 50% in July compared to last year, according to UMIH Prestige, which represents hotels charging at least €800 ($865) a night for rooms.

Earlier this year, high-end restaurants and concierges said the Olympics might even be an opportunity to score a hard-get-seat at the city’s fine dining.

In the Occitanie region in southwest France, the overall number of reservations this summer hasn’t changed much from last year, says Vincent Gare, president of the regional tourism committee there.

“But looking further at the numbers, we do see an increase in the clientele coming from the Paris region,” Gare told Le Figaro, noting that the increase in reservations has fallen directly on the dates of the Olympic games.

Michel Barré, a retiree living in Paris’s Le Marais neighbourhood, is one of those opting for the beach rather than the opening ceremony. In January, he booked a stay in Normandy for two weeks.

“Even though it’s a major European capital, Paris is still a small city—it’s a massive effort to host all of these events,” Barré says. “The Olympics are going to be a mess.”

More than anything, he just wants some calm after an event-filled summer in Paris, which just before the Olympics experienced the drama of a snap election called by Macron.

“It’s been a hectic summer here,” he says.

AFP via Getty Images

Parisians—Barré included—feel that the city, by over-catering to its tourists, is driving out many residents.

Parts of the Seine—usually one of the most popular summertime hangout spots —have been closed off for weeks as the city installs bleachers and Olympics signage. In certain neighbourhoods, residents will need to scan a QR code with police to access their own apartments. And from the Olympics to Sept. 8, Paris is nearly doubling the price of transit tickets from €2.15 to €4 per ride.

The city’s clear willingness to capitalise on its tourists has motivated some residents to do the same. In March, the number of active Airbnb listings in Paris reached an all-time high as hosts rushed to list their apartments. Listings grew 40% from the same time last year, according to the company.

With their regular clients taking off, Parisian restaurants and merchants are complaining that business is down.

“Are there any Parisians left in Paris?” Alaine Fontaine, president of the restaurant industry association, told the radio station Franceinfo on Sunday. “For the last three weeks, there haven’t been any here.”

Still, for all the talk of those leaving, there are plenty who have decided to stick around.

Jay Swanson, an American expat and YouTuber, can’t imagine leaving during the Olympics—he secured his tickets to see ping pong and volleyball last year. He’s also less concerned about the crowds and road closures than others, having just put together a series of videos explaining how to navigate Paris during the games.

“It’s been 100 years since the Games came to Paris; when else will we get a chance to host the world like this?” Swanson says. “So many Parisians are leaving and tourism is down, so not only will it be quiet but the only people left will be here for a party.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.