Car Dealers on Why Some Customers Hesitate With EVs

Concern about electric vehicles’ appeal is mounting as some customers show a reluctance to switch

Auto dealers across many parts of the country say electric vehicles are becoming too hard a sell for buyers worried about the range, reliability and price of these models.

When Paul LaRochelle heard Ford Motor was coming out with an electric pickup truck, the dealer was excited about the prospects for his business.

“We thought we could build a million of them and sell them,” said LaRochelle, a vice president at Sheehy Auto Stores, which sells vehicles from a dozen brands in Virginia, Maryland and Washington, D.C.

The reality has been less positive. On Sheehy’s car lots, LaRochelle says there is a six- to 12-month supply of EVs, compared with a month of gasoline-powered vehicles.

With automakers set to release a barrage of new electric models in the coming years, concerns are mounting among auto retailers about whether the technology will have broader appeal given that many customers are still reluctant to make the switch.

Battery-powered models have been piling up on car lots, dealers say, as EV sales growth has slowed in the U.S. this year. Car companies have been offering a combination of discounts and lower interest-rate deals in an effort to juice demand. But it hasn’t been enough, because buyer reticence extends beyond the price tag, dealers say.

“I’m not hearing the consumer confidence in the technology,” said Mary Rice, dealer principal at Toyota of Greensboro in North Carolina. “People aren’t beating down the door to buy these things, and they all have a different excuse why they aren’t buying one.”

Customers cite concerns about vehicles burning through a battery charge faster in cold weather or not being able to travel as far as they expected on a single charge, dealers say. Potential buyers also worry that chargers aren’t as readily accessible as gas stations or might be broken.

Franchise dealerships fear that the push to roll out new models will inundate them with hard-to-sell vehicles. Research firm S&P Global Mobility said there are 56 EV models for sale in the U.S. this year, and the number is expected to nearly double to 100 next year.

“I start to think, you know maybe we should just all pump the brakes a little bit,” Rice said.

A group of dealers expressed their concerns about the government’s role in pushing electric vehicles in a letter last month to President Biden.

A Toyota Motor spokesman said the majority of dealers have become “increasingly more confident in their ability to sell Toyota EV products.”

At Ford, the company’s electric-vehicle sales are rising, including for its F-150 Lightning pickup, but demand isn’t evenly spread across the country, according to a spokesman.

Dealers say that after selling an EV, they sometimes hear complaints about charging and the vehicles not always meeting their advertised range. In some cases, customers seek to return them to the dealer shortly after buying them.

“We have a steady number of clients that have attempted to or flat out returned their car,” said Sheehy’s LaRochelle.

While EVs remain a small but rapidly expanding part of the new-car market, the pace of growth has slowed this year. Electric-vehicle sales increased 48% in the first 11 months, compared with a 69% jump during the same period in 2022, according to Motor Intelligence. Sales remain concentrated in a few states, with California accounting for the largest chunk, S&P Global Mobility data found.

The cooling growth has raised broader questions in the industry about whether car companies face a temporary hurdle or a longer-term demand challenge. Automakers have invested billions of dollars to bring more EV models to the market, and many analysts and car executives say they remain optimistic that sales will continue to expand.

“Although the rate of growth has slowed recently, EV demand is clearly moving in the right direction,” said General Motors Chief Executive Mary Barra on a recent conference call with analysts. A combination of more affordable model options and better charging infrastructure would help encourage more people to buy electric vehicles, she said.

There are also varying views within the dealer community about how quickly buyers will adopt the technology.In hot spots for electric-vehicle demand, such as Los Angeles, dealers say their battery-powered models are some of their top sellers. Those popular EV markets also tend to have more mature public charging networks.

Selling an electric car or truck outside of those demand centres is proving more difficult.

Longtime EV owner Carmella Roehrig thought she was ready to go full-electric and sold her backup gasoline vehicle. But after the 62-year-old North Carolina resident found herself stranded last year in a rural area of South Carolina, she changed her mind. Roehrig’s Tesla Model S got a flat tire, but none of the stores in the area carried tires for a Tesla. She ended up paying a worker at a nearby shop to drive her home.

Roehrig still has her Tesla but bought a pickup truck for long road trips.

Tesla didn’t respond to a request for comment.

“I have these conversations with people who say we’ll all be in EVs in 15 years. I say: ‘I’m not so sure. I’ve tried to do it,’” Roehrig said. “I think you need a gas backup.”

Customers who want to ditch their gas vehicle for environmental reasons are sometimes hesitant, said Mickey Anderson, president of Baxter Auto Group, which owns dealerships in Kansas, Nebraska and Colorado.

“We’re in the Colorado Springs market. If this is your sole mode of transportation, and you’re in a market in extremes of elevation and temperature, the actual range is very limited,” Anderson said. “It makes it extremely impractical.”

Dealers representing around 4,000 stores across the U.S. signed the letter in November addressed to Biden, saying the administration’s proposed auto-emissions regulations designed to promote electric-vehicle sales are unrealistic. The signatories ranged from stores owned by family businesses to publicly held giants such as AutoNation and Lithia Motors.

“Some customers are in the market for electric vehicles, and we are thrilled to sell them. But the majority of customers are simply not ready to make the change,” the letter said.

Some carmakers are pushing back EV-rollout plans. GM said in mid-October that it would delay the opening of an electric pickup plant by a year to late 2025. In response to weaker-than-expected consumer demand, Ford said in late October that it would defer $12 billion of planned spending on electric-vehicle investment.

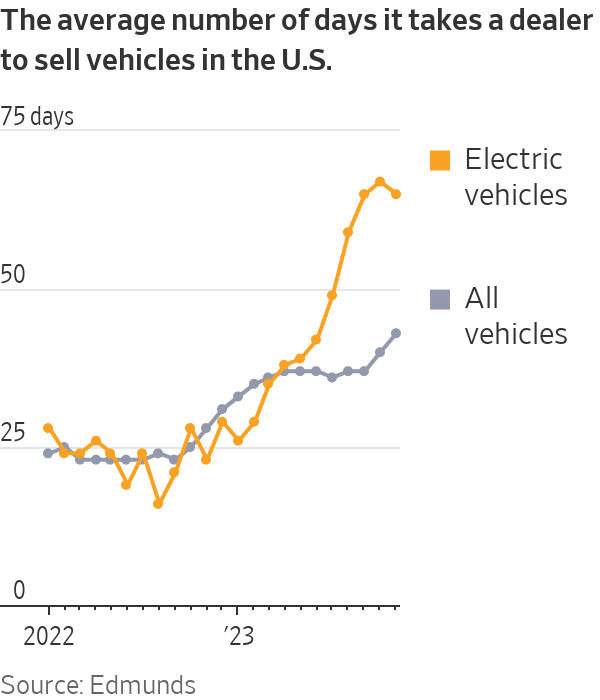

Since September, dealers on average took more than two months to sell an EV, compared with 40 days for all vehicles, according to car-shopping website Edmunds.

While discounts have helped boost sales of some electric vehicles, they also have led to repercussions for some current owners because it reduces the value of their vehicles, dealers say.

“Most people don’t have the confidence to buy an EV and know what it will be worth in 10-15 years,” said Rice from the Toyota dealership.

It may take some time for the industry to adjust because it is still in an early stage of switching to electric vehicles, Sheehy’s LaRochelle said.

“We’re asking for this market to grow organically,” he said.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

As Paris makes its final preparations for the Olympic games, its residents are busy with their own—packing their suitcases, confirming their reservations, and getting out of town.

Worried about the hordes of crowds and overall chaos the Olympics could bring, Parisians are fleeing the city in droves and inundating resort cities around the country. Hotels and holiday rentals in some of France’s most popular vacation destinations—from the French Riviera in the south to the beaches of Normandy in the north—say they are expecting massive crowds this year in advance of the Olympics. The games will run from July 26-Aug. 1.

“It’s already a major holiday season for us, and beyond that, we have the Olympics,” says Stéphane Personeni, general manager of the Lily of the Valley hotel in Saint Tropez. “People began booking early this year.”

Personeni’s hotel typically has no issues filling its rooms each summer—by May of each year, the luxury hotel typically finds itself completely booked out for the months of July and August. But this year, the 53-room hotel began filling up for summer reservations in February.

“We told our regular guests that everything—hotels, apartments, villas—are going to be hard to find this summer,” Personeni says. His neighbours around Saint Tropez say they’re similarly booked up.

As of March, the online marketplace Gens de Confiance (“Trusted People”), saw a 50% increase in reservations from Parisians seeking vacation rentals outside the capital during the Olympics.

Already, August is a popular vacation time for the French. With a minimum of five weeks of vacation mandated by law, many decide to take the entire month off, renting out villas in beachside destinations for longer periods.

But beyond the typical August travel, the Olympics are having a real impact, says Bertille Marchal, a spokesperson for Gens de Confiance.

“We’ve seen nearly three times more reservations for the dates of the Olympics than the following two weeks,” Marchal says. “The increase is definitely linked to the Olympic Games.”

Getty Images

According to the site, the most sought-out vacation destinations are Morbihan and Loire-Atlantique, a seaside region in the northwest; le Var, a coastal area within the southeast of France along the Côte d’Azur; and the island of Corsica in the Mediterranean.

Meanwhile, the Olympics haven’t necessarily been a boon to foreign tourism in the country. Many tourists who might have otherwise come to France are avoiding it this year in favour of other European capitals. In Paris, demand for stays at high-end hotels has collapsed, with bookings down 50% in July compared to last year, according to UMIH Prestige, which represents hotels charging at least €800 ($865) a night for rooms.

Earlier this year, high-end restaurants and concierges said the Olympics might even be an opportunity to score a hard-get-seat at the city’s fine dining.

In the Occitanie region in southwest France, the overall number of reservations this summer hasn’t changed much from last year, says Vincent Gare, president of the regional tourism committee there.

“But looking further at the numbers, we do see an increase in the clientele coming from the Paris region,” Gare told Le Figaro, noting that the increase in reservations has fallen directly on the dates of the Olympic games.

Michel Barré, a retiree living in Paris’s Le Marais neighbourhood, is one of those opting for the beach rather than the opening ceremony. In January, he booked a stay in Normandy for two weeks.

“Even though it’s a major European capital, Paris is still a small city—it’s a massive effort to host all of these events,” Barré says. “The Olympics are going to be a mess.”

More than anything, he just wants some calm after an event-filled summer in Paris, which just before the Olympics experienced the drama of a snap election called by Macron.

“It’s been a hectic summer here,” he says.

AFP via Getty Images

Parisians—Barré included—feel that the city, by over-catering to its tourists, is driving out many residents.

Parts of the Seine—usually one of the most popular summertime hangout spots —have been closed off for weeks as the city installs bleachers and Olympics signage. In certain neighbourhoods, residents will need to scan a QR code with police to access their own apartments. And from the Olympics to Sept. 8, Paris is nearly doubling the price of transit tickets from €2.15 to €4 per ride.

The city’s clear willingness to capitalise on its tourists has motivated some residents to do the same. In March, the number of active Airbnb listings in Paris reached an all-time high as hosts rushed to list their apartments. Listings grew 40% from the same time last year, according to the company.

With their regular clients taking off, Parisian restaurants and merchants are complaining that business is down.

“Are there any Parisians left in Paris?” Alaine Fontaine, president of the restaurant industry association, told the radio station Franceinfo on Sunday. “For the last three weeks, there haven’t been any here.”

Still, for all the talk of those leaving, there are plenty who have decided to stick around.

Jay Swanson, an American expat and YouTuber, can’t imagine leaving during the Olympics—he secured his tickets to see ping pong and volleyball last year. He’s also less concerned about the crowds and road closures than others, having just put together a series of videos explaining how to navigate Paris during the games.

“It’s been 100 years since the Games came to Paris; when else will we get a chance to host the world like this?” Swanson says. “So many Parisians are leaving and tourism is down, so not only will it be quiet but the only people left will be here for a party.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.