Four Stars for Peeling Paint and Broken Doors? What’s Behind High Airbnb Ratings

With a jump in rental properties on Airbnb, hosts care more than ever about their ratings, and some guests feel pressure to give positive reviews

Airbnb properties have a grading problem, hosts and guests say: Most U.S. rentals earn near the top rating of five stars.

Hosts are facing more competition for bookings because Airbnb has added more properties for rent, and as a result hosts say their ratings matter more to set them apart. Some hosts are experiencing what they’ve named an “Airbnbust,” or a drop-off in bookings due to the jump in short-term rental properties.

Adding to the pressure is the Airbnb algorithm that determines which “three-bedroom-with-a-pool-and-fire pit” comes up during a guest’s search. Superhosts who have an overall average of at least 4.8 stars—among other factors—typically earn more than regular hosts. The Airbnb algorithm factors in many criteria, including availability, price, responsiveness of host, number of cancellations by the host, as well as superhost status when ordering search results. Also, hosts who receive repeated ratings of one to three stars are told to improve or risk being delisted.

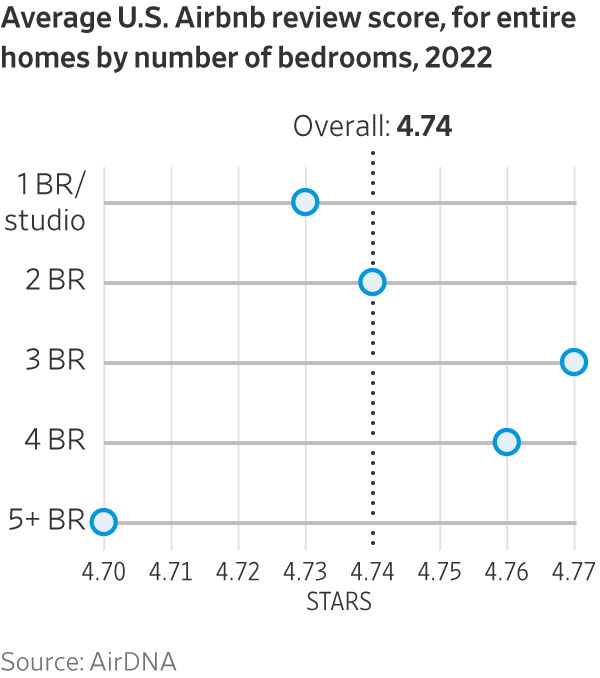

The average rating for homes in the U.S. on Airbnb, excluding room rentals, was 4.74 stars in 2022, with nearly identical or identical averages in 2021 and 2019, according to market research firm AirDNA.

With most listings ranking above 4.5 stars, guests say they can have trouble discerning what separates a 4.6-star property from a 4.8-star property. Others admit to leaving a positive review so as not to harm the host—or receive a negative review of their performance as a guest in turn.

Recently, at an Atlanta Airbnb currently rated 4.67, the doorknob on an automatic door to the bedroom got jammed, trapping Ashanti Carey inside. The 25-year-old lawyer from Kansas City, Mo., was visiting Atlanta with her mom and sister, who had to pull on the door from the outside to free her. She left after one night.

The host issued a partial refund, Ms. Carey says. Ms. Carey says she didn’t want to leave a five-star review due to getting locked in a bedroom, and because the property was dirty and dated. But she also didn’t want to damage the host’s livelihood.

She left four stars and a vague reference to her experience, mentioning she only stayed one of three nights “due to some issues with the property.” The house could be a good fit if the host made improvements, she wrote in her review.

“I felt somewhat pressured to not necessarily be forthright,” she says, adding that she is more skeptical of reviews now.

Airbnb says its reviews aren’t inflated. The company believes most guests leave ratings and reviews that authentically reflect their experiences, a spokeswoman said in an email. The company says it removes hosts who consistently earn poor ratings and don’t show signs of improvement, which is why most available listings are highly rated.

U.S. short-term rental availability hit a peak in 2022, according to AirDNA. Airbnb said in an earnings call that it added more than 900,000 listings globally in 2022, a 16% increase from the previous year, excluding listings in China.

More than 120 million reviews were left between hosts and guests on Airbnb between Oct. 1, 2021 and Sept. 30, 2022, the company says.

Airbnb guests rate rentals on factors including cleanliness, location and communication from the host. Some hosts are taking it upon themselves to ask guests for high ratings, both directly, which runs afoul of the platform’s rules, and by posting signs in their rentals.

Airbnb’s rules state: “Members of the Airbnb community may not coerce, intimidate, extort, threaten, incentivise or manipulate another person in an attempt to influence a review.”

Erin Kirkpatrick started renting out her two-bedroom apartment in downtown Burlington, Vt., this past fall. After more than 30 guests, she earned superhost status with a 5.0 rating.

Then, earlier this year, one guest said Ms. Kirkpatrick was very accommodating and the unit was “immaculate” — and left four stars for the overall rating. A second four-star overall rating dropped Ms. Kirkpatrick’s overall rating from 4.98 to 4.91, which alarmed the superhost, she said, because she needs an overall average of at least 4.8 stars to keep the status.

Ms. Kirkpatrick said she wondered what, if anything, she could have done differently. She says she’s now more conscious of her pricing so that guests feel that they’re getting a good value. She says she won’t charge $500 a night during an upcoming college graduation weekend despite demand, so her guests who do book feel they’re getting a good value. She makes sure to keep snacks, water and seltzer in the unit well stocked.

Her two most recent guests rated her apartment five stars for the overall experience.

Online reviews proliferate, and some other travel sites such as Yelp and Tripadvisor focus on stamping out fake reviews from people who have never visited a hotel or eaten at the restaurant that they rave about or trash.

Airbnb says it works to make the review system as fair as possible, including only allowing reviews between hosts and guests with confirmed bookings and requiring reviews within 14 days of checkout so they are timely. At Airbnb’s smaller rival Vrbo, top hosts have at least a 4.3 overall rating, the company says, and the average rating globally is 4.6 stars out of 5.

People who leave ratings on sites where they themselves are also rated, as with services including ride-sharing services Uber and Lyft and Vrbo, are generally more likely to leave positive reviews, researchers say.

“It’s very different when you’re dealing with a big, faceless corporation like an airline versus an individual human,” says Camilla Vásquez, a professor of linguistics at the University of South Florida who has been studying online review systems for over a decade.

As short-term rentals have exploded, travelers have increasingly made direct comparisons to hotels, where the number of stars signifies the quality of the property, hosts say.

Airbnb says it provides guests with definitions of the overall star rating and individual category star ratings. For the overall rating, a five-star stay is defined as great, a four star stay is good, and three stars is OK.

Still, many hosts say the rating system isn’t clear enough to guests or to hosts.

Caitlin Bates, who rents out her property outside of Sedona, Ariz., on Airbnb, made a refrigerator magnet to guide her guests. Five stars means the guest enjoyed their stay and any issues were addressed. Four stars means the experience was just “ok” and issues weren’t addressed. The dreaded one star equals a “horrific experience.” The magnet says hosts with less than 4.7 stars are at risk of being delisted, something Ms. Bates says she heard from other Airbnb hosts. She sells the magnet on Etsy for prices starting at $10.95 and estimates she has sold at least 300.

Ms. Bates has an average rating of 4.94.

Airbnb says it doesn’t automatically remove hosts with averages under 4.7 stars. Listings might be removed if there are severe or repeated instances of not meeting quality standards, a spokeswoman said. Ms. Bates’s magnets aren’t endorsed by Airbnb or an accurate reflection of the company’s review system or policies, the spokeswoman said.

Airbnb hosts who receive multiple low ratings—one to three stars—may receive an automated email from the company. The subject line: “Improve your ratings to keep your listings active.” Listings receiving a rating between one and three stars are at higher risk of being suspended, which means the property will be removed from search for five days, according to the email. The emails also provide resources and tips to hosts to help them improve, Airbnb says.

Some guests choose to give low ratings in the hopes of getting freebies such as a refund, hosts say. It is against Airbnb policy for guests to leave negative reviews to punish hosts for enforcing the property’s rules.

Airbnb says it generally doesn’t mediate disputes over the truth of reviews. The company encourages hosts and guests to post responses to reviews within 30 days as the main form of recourse for what they see as unfair reviews. People can report reviews that violate Airbnb’s policy, and the company will investigate whether to remove them.

A recent Airbnb rental that was rated 4.8 stars had ratty furniture and he could hear noise from a bar down the street, says Baird Kleinsmith, a 40-year-old from Durango, Colo. In another, rated 4.6, there were water stains on the walls and the apartment was beat up, he says.

So he gave them bad reviews, including rating one a 1 star. In the past, Mr. Kleinsmith, who rents from Airbnb about 10 times a year, seldom left ratings under four stars because he didn’t want to harm the host, he says. “As a guest, I want to know from prior guests what was good and what was bad about the property,” says the owner of multiple self-storage facilities.

“So I’ve changed my approach.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

As Paris makes its final preparations for the Olympic games, its residents are busy with their own—packing their suitcases, confirming their reservations, and getting out of town.

Worried about the hordes of crowds and overall chaos the Olympics could bring, Parisians are fleeing the city in droves and inundating resort cities around the country. Hotels and holiday rentals in some of France’s most popular vacation destinations—from the French Riviera in the south to the beaches of Normandy in the north—say they are expecting massive crowds this year in advance of the Olympics. The games will run from July 26-Aug. 1.

“It’s already a major holiday season for us, and beyond that, we have the Olympics,” says Stéphane Personeni, general manager of the Lily of the Valley hotel in Saint Tropez. “People began booking early this year.”

Personeni’s hotel typically has no issues filling its rooms each summer—by May of each year, the luxury hotel typically finds itself completely booked out for the months of July and August. But this year, the 53-room hotel began filling up for summer reservations in February.

“We told our regular guests that everything—hotels, apartments, villas—are going to be hard to find this summer,” Personeni says. His neighbours around Saint Tropez say they’re similarly booked up.

As of March, the online marketplace Gens de Confiance (“Trusted People”), saw a 50% increase in reservations from Parisians seeking vacation rentals outside the capital during the Olympics.

Already, August is a popular vacation time for the French. With a minimum of five weeks of vacation mandated by law, many decide to take the entire month off, renting out villas in beachside destinations for longer periods.

But beyond the typical August travel, the Olympics are having a real impact, says Bertille Marchal, a spokesperson for Gens de Confiance.

“We’ve seen nearly three times more reservations for the dates of the Olympics than the following two weeks,” Marchal says. “The increase is definitely linked to the Olympic Games.”

Getty Images

According to the site, the most sought-out vacation destinations are Morbihan and Loire-Atlantique, a seaside region in the northwest; le Var, a coastal area within the southeast of France along the Côte d’Azur; and the island of Corsica in the Mediterranean.

Meanwhile, the Olympics haven’t necessarily been a boon to foreign tourism in the country. Many tourists who might have otherwise come to France are avoiding it this year in favour of other European capitals. In Paris, demand for stays at high-end hotels has collapsed, with bookings down 50% in July compared to last year, according to UMIH Prestige, which represents hotels charging at least €800 ($865) a night for rooms.

Earlier this year, high-end restaurants and concierges said the Olympics might even be an opportunity to score a hard-get-seat at the city’s fine dining.

In the Occitanie region in southwest France, the overall number of reservations this summer hasn’t changed much from last year, says Vincent Gare, president of the regional tourism committee there.

“But looking further at the numbers, we do see an increase in the clientele coming from the Paris region,” Gare told Le Figaro, noting that the increase in reservations has fallen directly on the dates of the Olympic games.

Michel Barré, a retiree living in Paris’s Le Marais neighbourhood, is one of those opting for the beach rather than the opening ceremony. In January, he booked a stay in Normandy for two weeks.

“Even though it’s a major European capital, Paris is still a small city—it’s a massive effort to host all of these events,” Barré says. “The Olympics are going to be a mess.”

More than anything, he just wants some calm after an event-filled summer in Paris, which just before the Olympics experienced the drama of a snap election called by Macron.

“It’s been a hectic summer here,” he says.

AFP via Getty Images

Parisians—Barré included—feel that the city, by over-catering to its tourists, is driving out many residents.

Parts of the Seine—usually one of the most popular summertime hangout spots —have been closed off for weeks as the city installs bleachers and Olympics signage. In certain neighbourhoods, residents will need to scan a QR code with police to access their own apartments. And from the Olympics to Sept. 8, Paris is nearly doubling the price of transit tickets from €2.15 to €4 per ride.

The city’s clear willingness to capitalise on its tourists has motivated some residents to do the same. In March, the number of active Airbnb listings in Paris reached an all-time high as hosts rushed to list their apartments. Listings grew 40% from the same time last year, according to the company.

With their regular clients taking off, Parisian restaurants and merchants are complaining that business is down.

“Are there any Parisians left in Paris?” Alaine Fontaine, president of the restaurant industry association, told the radio station Franceinfo on Sunday. “For the last three weeks, there haven’t been any here.”

Still, for all the talk of those leaving, there are plenty who have decided to stick around.

Jay Swanson, an American expat and YouTuber, can’t imagine leaving during the Olympics—he secured his tickets to see ping pong and volleyball last year. He’s also less concerned about the crowds and road closures than others, having just put together a series of videos explaining how to navigate Paris during the games.

“It’s been 100 years since the Games came to Paris; when else will we get a chance to host the world like this?” Swanson says. “So many Parisians are leaving and tourism is down, so not only will it be quiet but the only people left will be here for a party.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.