‘How Do I Do That?’ The New Hires of 2023 Are Unprepared for Work

Remote learning during the pandemic left students short of basic skills. Now companies are trying to teach them on the job.

Roman Devengenzo was consulting for a robotics company in Silicon Valley last fall when he asked a newly minted mechanical engineer to design a small aluminum part that could be fabricated on a lathe—a skill normally mastered in the first or second year of college.

“How do I do that?” asked the young man.

So Devengenzo, an engineer who has built technology for NASA and Google, and who charges consulting clients a minimum of $300 an hour, spent the next three hours teaching Lathework 101. “You learn by doing,” he said. “These kids in school during the pandemic, all they’ve done is work on computers.”

The knock-on effect of years of remote learning during the pandemic is gumming up workplaces around the country. It is one reason professional service jobs are going unfilled and goods aren’t making it to market. It also helps explain why national productivity has fallen for the past five quarters, the longest contraction since at least 1948, according to the U.S. Labor Department.

The shortcomings run the gamut from general knowledge, including how to make change at a register, to soft skills such as working with others. Employers are spending more time and resources searching for candidates and often lowering expectations when they hire. Then they are spending millions to fix new employees’ lack of basic skills.

Talent First, a business-led workforce-development organisation in Grand Rapids, Mich., is encouraging employers to stop trying to hire based on skill. Instead, hiring managers should look for a willingness to learn, said President Kevin Stotts.

“Employers are saying, ‘We’re just trying to find some people who could fog the mirror,’ ” Stotts said.

Since 2020, when the pandemic began and remote learning moved students out of schools and into virtual classrooms, the pass rates on national certifications and assessment exams taken by engineers, office workers, soldiers and nurses have all fallen.

Among the approximately 40,000 candidates taking the Fundamentals of Engineering exam for work as professional engineers, scores fell by about 10% during the pandemic, said David Cox, CEO of the National Council of Examiners for Engineering and Surveying.

That means fewer engineers on the job and a lower degree of competency among those who make it, he said.

The sharpest declines in scores came on questions measuring the most specialised knowledge. Structural engineers failed to answer questions about the use of trusses in the construction of bridges and roadways, Cox said.

“These are areas that are very much involved in public safety,” he said.

Students in elementary and middle schools across the nation fell behind by an average of about four months during the pandemic after classes switched to remote learning in 2020 and stayed that way in some cases through 2021. On national standardised tests, the scores of fourth- and eighth-graders fell to 30-year lows.

Students who were in high-school and college when Covid-19 hit and are now entering the workforce didn’t fare much better. Despite lowered standards at many schools during the pandemic, high-school graduation rates fell. Scores for college admissions exams dropped to the lowest level in three decades.

Janet Godwin, chief executive of ACT, the nonprofit organisation which administers the college admission test of the same name, said more high-school graduates today lack the fundamental academic skills needed for college and the workplace, with low-performing students facing the steepest declines.

In Covid-19’s aftermath, many college professors restructured curricula for students who lack basic study skills.

“Reading, writing and critical-thinking skills are not the same as they were in the past,” said Mike Altman, a religion professor at the University of Alabama who said he has narrowed his curriculum to give his students more time to master basics.

During the pandemic more than 100,000 nurses left the field, the largest decline in four decades of available data, a study in the journal Health Affairs showed. That has placed tremendous strain on hospitals and increased demands on programs to graduate more nurses. But students taking entrance exams to study nursing are scoring an average of about 5 percentage points lower than before the pandemic, limiting the number of students eligible to enrol in nursing programs.

More students who do enrol struggle to earn passing grades, said Patty Knecht, Vice President of Ascend Learning Healthcare, a private company which helps train medical professionals. And even if they do graduate, more are struggling to pass a certification exam. By then, they may already be on the payroll but unable to work. The delays cost hospitals an average of $42,000 per student who fails the certification exam, said Knecht.

Last year, Ivy Tech Community College, the largest nursing program in Indiana, embedded tutors in classrooms to assist lagging students with skills they should have mastered in high school. Some of the most basic included the math necessary to figure out correct dosages for medicine.

Joseph Mulumba, who is about to start his sophomore year in the Ivy Tech nursing program, was a high-school sophomore in Indiana when the pandemic arrived. His school was remote for a year.

“I feel like I would have learned a lot more if not for the pandemic,” Mulumba said. “When I got here I realised I wasn’t ready for nursing school. I realised I didn’t know how to study.”

Jerrica Moses, national recruitment manager for Senture, a London, Ky.-based call-centre company, says new workers have problems with soft skills, such as an inability to deal with frustration. Senture, which employs about 4,200 customer-service representatives, has adopted a new set of tests to determine which prospective employees will be able to keep their cool under stress from angry or rude callers.

“Candidates who wash out respond by explaining how aggravated they get with the callers and then focus on the stress,” said Moses. Most of the people who struggle are under 25 years old, she added.

In Grand Rapids, managers at the John Ball Zoo are coaching seasonal workers in their teens and early 20s on basics such as why it’s important to look visitors in the eye, and how to make change at a cash register.

They are also trying to instil a work ethic in their employees that includes taking some initiative, getting off their phones and engaging with visitors, said Laura Davis, the director of strategy and organisational development at the zoo. Her young employees haven’t been held accountable for things like finishing homework assignments, and Davis believes that has led to a decline in motivation.

“They’re not looking to be productive,” Davis said. “If they’re not told what to do, if someone isn’t managing every second and keeping them busy, their inclination is not to self identify what they can do—it’s to do nothing.”

The pandemic arrived when Ivan Schury was in the eighth grade. Now 17 years old and a supervisor in the zoo’s kitchen, he said the isolation he and his peers experienced over the next few years have left many distracted and disengaged.

Last week a teenager working the fry station kept wandering off. “He just kept walking away to talk to his friends at the counter,” Schury said. “I spend a lot of time making sure people stay on task.”

Charity Fields, 19 years old, works in the gift shop and says she is frequently surprised by the lack of motivation of her younger co-workers. A few days ago a 16-year-old fellow sales associate sat in a chair reading a book while customers shopped.

“I told her we weren’t really supposed to do that,” Fields said. The girl got up, stood near the cash register, leaned on the counter and continued to read.

The problem extends to the U.S. military, exacerbating pressures the services face from poor recruiting.

Army recruits aren’t communicating within their squads as well as they did before the pandemic, instructors say. Scores on recruiting exams fell 9% since the pandemic and prompted the Army to create a new testing boot camp to help recruits pass, a requirement for gaining admission to the military.

Army Secretary Christine Wormuth believes a lot of the struggles are tied into isolation that took root when students learned remotely during the pandemic.

“So many young people spent two years in relative isolation and not doing a lot of group projects,” she said.

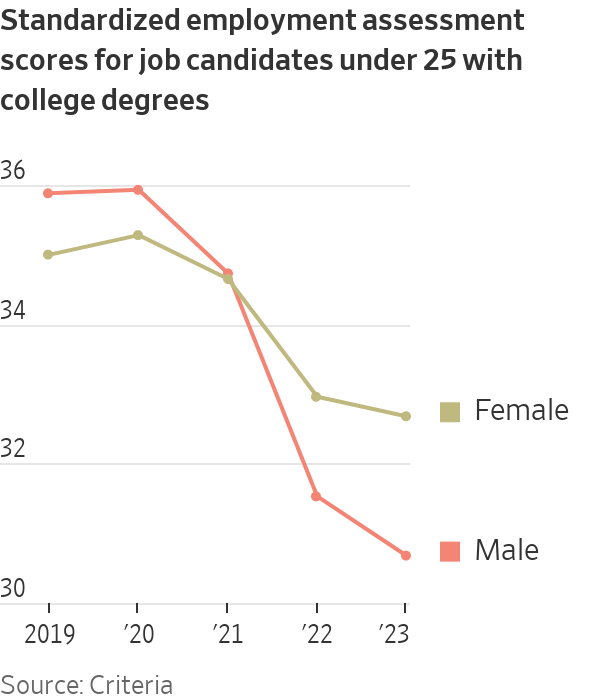

Young workers’ struggles have become vividly apparent to Criteria Corp, a Los Angeles company that administers about 10 million assessments a year to evaluate prospective employees.

Results for test takers overall have held steady with a notable decline in the scores of men between 18 and 24 and usually with a high-school education, said Josh Millet, co-founder and CEO of the company.

The company’s Criteria Basic Skills Test measures reading comprehension, verbal skills and numeracy. Companies use it to hire for positions such as administrative assistants, customer-service representatives, medical assistants, insurance salespeople and bank tellers.

Verbal scores for men under 25 declined by 11 percentage points over the three years of the pandemic. Scores for women were less dramatically affected. The biggest dips among men were registered in communication skills, reading comprehension, grammar, spelling and attention to detail, said Millet.

“Our customers consistently tell us that finding high-quality candidates is the single greatest challenge to the successful execution of their talent strategies, and it seems that diminished educational outcomes may exacerbate that challenge,” Millet said.

Cindy Neal, owner of Express Employment Professionals in Peoria, Ill., places about 1,500 people in jobs every year. Since the pandemic, she has seen sharp declines in the behaviour of job applicants as well as their performance on employment exams.

The company has long offered courses for people to gain new skills such as QuickBooks. This spring they added new courses to help prospective workers with soft skills. Some of the chapters taught include taking initiative, personal productivity, cellphone etiquette, workplace hygiene, dressing appropriately for work and handling conflict with co-workers.

“This stuff used to be taught in schools,” Neal said. “Now people have to be told not to bring their kids to work.”

Results on the 15-minute employment exam the company administers to clients when they walk in the door are also declining.

Tasks on the quiz include recognising misspellings in words like “availability,” “repetition” and “privilege,” and math questions such as: “If you were asked to load 225 boxes onto a truck and the boxes are crated, with each crate containing nine boxes, how many crates would you need to load?”

The scores in math and spelling are the worst she’s seen in 30 years, she said, adding, “I’m really concerned by the product that’s coming out of the school system currently.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

As Paris makes its final preparations for the Olympic games, its residents are busy with their own—packing their suitcases, confirming their reservations, and getting out of town.

Worried about the hordes of crowds and overall chaos the Olympics could bring, Parisians are fleeing the city in droves and inundating resort cities around the country. Hotels and holiday rentals in some of France’s most popular vacation destinations—from the French Riviera in the south to the beaches of Normandy in the north—say they are expecting massive crowds this year in advance of the Olympics. The games will run from July 26-Aug. 1.

“It’s already a major holiday season for us, and beyond that, we have the Olympics,” says Stéphane Personeni, general manager of the Lily of the Valley hotel in Saint Tropez. “People began booking early this year.”

Personeni’s hotel typically has no issues filling its rooms each summer—by May of each year, the luxury hotel typically finds itself completely booked out for the months of July and August. But this year, the 53-room hotel began filling up for summer reservations in February.

“We told our regular guests that everything—hotels, apartments, villas—are going to be hard to find this summer,” Personeni says. His neighbours around Saint Tropez say they’re similarly booked up.

As of March, the online marketplace Gens de Confiance (“Trusted People”), saw a 50% increase in reservations from Parisians seeking vacation rentals outside the capital during the Olympics.

Already, August is a popular vacation time for the French. With a minimum of five weeks of vacation mandated by law, many decide to take the entire month off, renting out villas in beachside destinations for longer periods.

But beyond the typical August travel, the Olympics are having a real impact, says Bertille Marchal, a spokesperson for Gens de Confiance.

“We’ve seen nearly three times more reservations for the dates of the Olympics than the following two weeks,” Marchal says. “The increase is definitely linked to the Olympic Games.”

Getty Images

According to the site, the most sought-out vacation destinations are Morbihan and Loire-Atlantique, a seaside region in the northwest; le Var, a coastal area within the southeast of France along the Côte d’Azur; and the island of Corsica in the Mediterranean.

Meanwhile, the Olympics haven’t necessarily been a boon to foreign tourism in the country. Many tourists who might have otherwise come to France are avoiding it this year in favour of other European capitals. In Paris, demand for stays at high-end hotels has collapsed, with bookings down 50% in July compared to last year, according to UMIH Prestige, which represents hotels charging at least €800 ($865) a night for rooms.

Earlier this year, high-end restaurants and concierges said the Olympics might even be an opportunity to score a hard-get-seat at the city’s fine dining.

In the Occitanie region in southwest France, the overall number of reservations this summer hasn’t changed much from last year, says Vincent Gare, president of the regional tourism committee there.

“But looking further at the numbers, we do see an increase in the clientele coming from the Paris region,” Gare told Le Figaro, noting that the increase in reservations has fallen directly on the dates of the Olympic games.

Michel Barré, a retiree living in Paris’s Le Marais neighbourhood, is one of those opting for the beach rather than the opening ceremony. In January, he booked a stay in Normandy for two weeks.

“Even though it’s a major European capital, Paris is still a small city—it’s a massive effort to host all of these events,” Barré says. “The Olympics are going to be a mess.”

More than anything, he just wants some calm after an event-filled summer in Paris, which just before the Olympics experienced the drama of a snap election called by Macron.

“It’s been a hectic summer here,” he says.

AFP via Getty Images

Parisians—Barré included—feel that the city, by over-catering to its tourists, is driving out many residents.

Parts of the Seine—usually one of the most popular summertime hangout spots —have been closed off for weeks as the city installs bleachers and Olympics signage. In certain neighbourhoods, residents will need to scan a QR code with police to access their own apartments. And from the Olympics to Sept. 8, Paris is nearly doubling the price of transit tickets from €2.15 to €4 per ride.

The city’s clear willingness to capitalise on its tourists has motivated some residents to do the same. In March, the number of active Airbnb listings in Paris reached an all-time high as hosts rushed to list their apartments. Listings grew 40% from the same time last year, according to the company.

With their regular clients taking off, Parisian restaurants and merchants are complaining that business is down.

“Are there any Parisians left in Paris?” Alaine Fontaine, president of the restaurant industry association, told the radio station Franceinfo on Sunday. “For the last three weeks, there haven’t been any here.”

Still, for all the talk of those leaving, there are plenty who have decided to stick around.

Jay Swanson, an American expat and YouTuber, can’t imagine leaving during the Olympics—he secured his tickets to see ping pong and volleyball last year. He’s also less concerned about the crowds and road closures than others, having just put together a series of videos explaining how to navigate Paris during the games.

“It’s been 100 years since the Games came to Paris; when else will we get a chance to host the world like this?” Swanson says. “So many Parisians are leaving and tourism is down, so not only will it be quiet but the only people left will be here for a party.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.