How IKEA Chopped, Hollowed Out and Flattened Its Furniture to Cut Costs

With inflation squeezing consumers and material and shipping prices up, the company took products back to the drawing board

ÄLMHULT, Sweden—Amid IKEA’s colourful staged living rooms, piles of umlaut-laden housewares and endless rows of flat-pack boxes is furniture that can have shoppers wondering: How does that chair cost only $35?

IKEA grew into a furniture behemoth with a relentless focus on keeping costs low, but that goal has become more challenging. The price of metal, glass, wood and plastic have spiralled up, as have shipping costs. Inflation has squeezed consumers’ wallets. Managers at IKEA knew that something had to change to keep prices down and profits up, so in the past couple of years they have taken some of their products back to the drawing board.

Designers experimented with ways to reduce IKEA’s reliance on wood—even in its trademark wooden furniture—to cut material and shipping costs. Lighter, less expensive plastics, they discovered, could be used instead in cabinet doors and drawers.

They learned that they could substitute less expensive recycled aluminium for zinc, which had doubled in price over two years to $4,371 per metric ton after the start of the Ukraine war. Recycled aluminium is now going into bathroom hooks and other products.

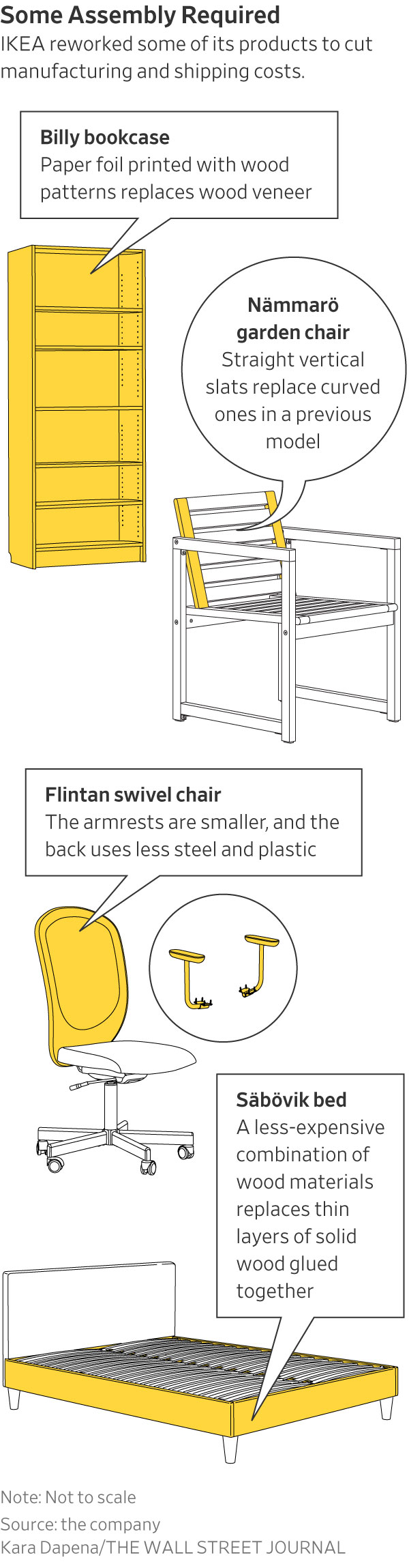

When they turned to packaging, they cut freight costs by purging flat packs of “fresh air and wasted space,” said Fredrika Inger, IKEA’s global range manager. On the new Nämmarö garden chair, the curved wooden slats featured on a previous model were straightened, which allowed the components to be packed more tightly together.

“Our budget is the customer’s wallet, and their wallets are smaller than ever,” said Susanne Waidzunas, global supply manager at Inter IKEA Holding BV, the company that owns the IKEA brand, develops its products and manages its supply chain.

Based in Älmhult in southern Sweden, where the late Ingvar Kamprad founded the company eight decades ago, IKEA is today the world’s biggest seller of furniture, with 460 mostly franchise-operated stores spread across 62 countries that carry some 9,500 products. Its in-store canteens serve 1 billion Swedish meatballs with cream sauce and lingonberry jam each year.

Mr. Kamprad, who died in 2018, believed in “democratic design”—essentially that everyday products should be attractive and functional, but also affordable. It was, in part, a hard-nosed strategy designed to maximize sales.

The challenges started with the disruptions of the Covid-19 pandemic, compounded by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Then high inflation presented many companies with a dilemma: raise prices to offset growing costs and risk alienating customers, or keep prices down and sacrifice profit margins. IKEA did some of both last year, and its annual profit halved, to 710 million euros, equivalent to $778 million, despite record sales.

As part of its push to boost profits, the company said last week it would spend 2 billion euros to open new U.S. locations over the next three years—its largest-ever investment in new American stores.

One of the company’s chief weapons in its fight to cut costs is the Billy bookcase, a bestseller considered the “heart of IKEA,” said Jesper Samuelsson, the product’s manager. Over 140 million units have been sold since it first appeared in the 1979 edition of the IKEA catalog. The company says someone, somewhere buys a Billy every five seconds—which comes out to around 6.3 million sales a year.

According to IKEA’s official history, the Billy’s original design was scribbled on a napkin after its creator, Gillis Lundgren, was inspired by criticism from IKEA’s then-advertising manager that the company’s bookcases lacked simplicity.

Now, Mr. Samuelsson said, IKEA colleagues have a game they play: “If you’re a product in IKEA, which one are you? I’m Billy—it’s a very simple, straightforward product.”

The Billy comes in two styles: white and wood finish. Its last major overhaul came in 1999, when the company changed its method for producing the white version. IKEA designers knocked a fifth off the unit’s price by replacing its white lacquer coating with a melamine foil.

It has been significantly cheaper than the wood-finish version ever since. In the U.S., the model that measures roughly 6½ feet tall and 2½ feet wide retails at $89.99 in white and $109.99 in wood finish. IKEA executives wanted to make the latter version less expensive, too, said Mr. Samuelsson.

Targeting a cost savings of 25% to 30%, Mr. Samuelsson and his colleagues focused on a solution that IKEA had been developing for years: the replacement of wood veneer with paper foil.

IKEA’s wooden furniture isn’t typically made of solid wood. Instead, it has traditionally used veneer, a thin slice of wood less than a millimetre thick that is glued onto a main structure of particleboard. Particleboard is formed from compacted wood chips and sawdust, and is significantly less expensive and lighter than solid wood.

Mr. Samuelsson knew that getting rid of the costly veneer would be key to savings, he said. The paper foil is less expensive, less wasteful and much quicker to apply than veneer, which speeds up the rate of production, Mr. Samuelsson said. Wrapped around the particleboard structure and printed with wood patterns, it looks like a wooden surface, he said.

IKEA first began to develop paper foil for use on its furniture around 2004, and has since steadily made the material less expensive and more reliable, gradually deploying it on other furniture lines, including the Pax wardrobe, one of the company’s bestselling bedroom closets.

By the time Mr. Samuelsson and his team of a dozen designers set about reworking the Billy in 2020, IKEA leaders had enough confidence in the paper foil to use it on their prize bookcase, he said. The Billy redesign brought some functional changes—including the replacement of metal nails with user-friendly plastic fasteners—but the switch from veneer to foil generated the cost savings that managers had been hoping for, he said.

The global rollout of the reworked version of the bookcase—produced in Sweden, Germany, Slovakia and China—has faced obstacles. Factories in Europe were already running at capacity, so the company would need to move slowly and carefully to introduce the new version without disrupting output. IKEA also realised its demand for paper foil would balloon, which required lengthy preparations to help suppliers build up their output.

Production of the new version started last year in China, where the local manufacturer had spare capacity and could implement the new production system sooner. The Billy is the country’s No. 1 IKEA product. There the wood-style bookcase is priced at 499 yuan, equivalent to about $72, down from 699 yuan—a 29% reduction. The white version sells for 399 yuan. The new Billy hits stores in the U.S. and Europe in early 2024.

These kinds of design changes are unlikely to alienate IKEA consumers, who typically don’t focus on how their furniture is made, said Tom Higgs, a furniture designer and lecturer at London’s Brunel University. “IKEA’s customers are looking for affordable, replaceable and convenient furniture,” he said.

For one of IKEA’s most popular office swivel chairs, the Flintan, smaller armrests and less steel and plastic in the back cut manufacturing costs. The new Flintan, which hit stores in 2021, is roughly the same size as its predecessor, but it’s much more efficient to ship after designers tweaked its components to make them fit more snugly into a flat pack. IKEA can now squeeze 6,900 Flintans into one shipping container, up from 2,750.

Even so, the company said that costs have increased so much that it decided to hold the chair’s price at $119 in the U.S. Without the design tweaks, the price would have risen significantly, it said.

IKEA designers likewise reworked the Säbövik bed, available in Europe but not the U.S., by changing the construction of its wooden frame. It was previously made of so-called sandwich board, comprising thin layers of wood glued together. Designers experimented with new material mixes before settling on a less expensive and lighter combination of solid wood, plywood and a compressed structure of wood strands and glue called oriented strand board.

The Säbövik used to come flat-packed in three cardboard boxes, but now fits into just two more compact boxes, enabling the company to cram twice as many flat-packed beds into a shipping container.

Tasked with developing a new extendible dining table that wouldn’t be prohibitively expensive, IKEA designers tried a novel approach.

Earlier IKEA tables typically used solid wood legs for strength and stability. In developing the new Rönninge table, which launched last year, designers created a leg made from hollow wood veneer with solid-wood inserts at the top and bottom to add strength. This approach significantly reduces material and freight costs since each leg now contains 90% less wood than if it had been made of solid wood, the company said. The Rönninge retails at $499 in the U.S.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

As Paris makes its final preparations for the Olympic games, its residents are busy with their own—packing their suitcases, confirming their reservations, and getting out of town.

Worried about the hordes of crowds and overall chaos the Olympics could bring, Parisians are fleeing the city in droves and inundating resort cities around the country. Hotels and holiday rentals in some of France’s most popular vacation destinations—from the French Riviera in the south to the beaches of Normandy in the north—say they are expecting massive crowds this year in advance of the Olympics. The games will run from July 26-Aug. 1.

“It’s already a major holiday season for us, and beyond that, we have the Olympics,” says Stéphane Personeni, general manager of the Lily of the Valley hotel in Saint Tropez. “People began booking early this year.”

Personeni’s hotel typically has no issues filling its rooms each summer—by May of each year, the luxury hotel typically finds itself completely booked out for the months of July and August. But this year, the 53-room hotel began filling up for summer reservations in February.

“We told our regular guests that everything—hotels, apartments, villas—are going to be hard to find this summer,” Personeni says. His neighbours around Saint Tropez say they’re similarly booked up.

As of March, the online marketplace Gens de Confiance (“Trusted People”), saw a 50% increase in reservations from Parisians seeking vacation rentals outside the capital during the Olympics.

Already, August is a popular vacation time for the French. With a minimum of five weeks of vacation mandated by law, many decide to take the entire month off, renting out villas in beachside destinations for longer periods.

But beyond the typical August travel, the Olympics are having a real impact, says Bertille Marchal, a spokesperson for Gens de Confiance.

“We’ve seen nearly three times more reservations for the dates of the Olympics than the following two weeks,” Marchal says. “The increase is definitely linked to the Olympic Games.”

Getty Images

According to the site, the most sought-out vacation destinations are Morbihan and Loire-Atlantique, a seaside region in the northwest; le Var, a coastal area within the southeast of France along the Côte d’Azur; and the island of Corsica in the Mediterranean.

Meanwhile, the Olympics haven’t necessarily been a boon to foreign tourism in the country. Many tourists who might have otherwise come to France are avoiding it this year in favour of other European capitals. In Paris, demand for stays at high-end hotels has collapsed, with bookings down 50% in July compared to last year, according to UMIH Prestige, which represents hotels charging at least €800 ($865) a night for rooms.

Earlier this year, high-end restaurants and concierges said the Olympics might even be an opportunity to score a hard-get-seat at the city’s fine dining.

In the Occitanie region in southwest France, the overall number of reservations this summer hasn’t changed much from last year, says Vincent Gare, president of the regional tourism committee there.

“But looking further at the numbers, we do see an increase in the clientele coming from the Paris region,” Gare told Le Figaro, noting that the increase in reservations has fallen directly on the dates of the Olympic games.

Michel Barré, a retiree living in Paris’s Le Marais neighbourhood, is one of those opting for the beach rather than the opening ceremony. In January, he booked a stay in Normandy for two weeks.

“Even though it’s a major European capital, Paris is still a small city—it’s a massive effort to host all of these events,” Barré says. “The Olympics are going to be a mess.”

More than anything, he just wants some calm after an event-filled summer in Paris, which just before the Olympics experienced the drama of a snap election called by Macron.

“It’s been a hectic summer here,” he says.

AFP via Getty Images

Parisians—Barré included—feel that the city, by over-catering to its tourists, is driving out many residents.

Parts of the Seine—usually one of the most popular summertime hangout spots —have been closed off for weeks as the city installs bleachers and Olympics signage. In certain neighbourhoods, residents will need to scan a QR code with police to access their own apartments. And from the Olympics to Sept. 8, Paris is nearly doubling the price of transit tickets from €2.15 to €4 per ride.

The city’s clear willingness to capitalise on its tourists has motivated some residents to do the same. In March, the number of active Airbnb listings in Paris reached an all-time high as hosts rushed to list their apartments. Listings grew 40% from the same time last year, according to the company.

With their regular clients taking off, Parisian restaurants and merchants are complaining that business is down.

“Are there any Parisians left in Paris?” Alaine Fontaine, president of the restaurant industry association, told the radio station Franceinfo on Sunday. “For the last three weeks, there haven’t been any here.”

Still, for all the talk of those leaving, there are plenty who have decided to stick around.

Jay Swanson, an American expat and YouTuber, can’t imagine leaving during the Olympics—he secured his tickets to see ping pong and volleyball last year. He’s also less concerned about the crowds and road closures than others, having just put together a series of videos explaining how to navigate Paris during the games.

“It’s been 100 years since the Games came to Paris; when else will we get a chance to host the world like this?” Swanson says. “So many Parisians are leaving and tourism is down, so not only will it be quiet but the only people left will be here for a party.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.