London’s Canary Wharf Takes Brunt of Real-Estate Pain

Empty offices, remote working and corporate tenants fleeing to buzzier areas hit the 30-year-old business district

LONDON—Three decades ago, London remade a derelict shipping yard at Canary Wharf into a forest of glass-and-concrete skyscrapers in a bid to mimic U.S. financial hubs.

Now the 128-acre banking district east of central London is suffering a problem also plaguing U.S. cities: emptying office buildings.

Last month, HSBC Holdings, the U.K.’s largest financial firm, said it was leaving its 1.1-million-square-foot headquarters, known as the HSBC Tower, for a smaller building in central London. The move followed a decision by law firm Clifford Chance to relocate to central London and major office-space downsizings by Barclays and Société Générale, among others.

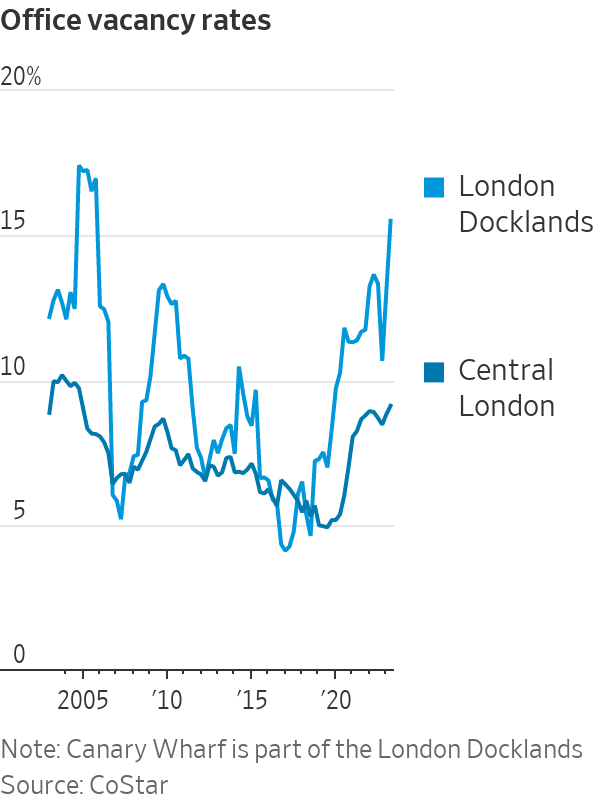

Already, Canary Wharf and its surrounding area have an availability rate of 17.1%, roughly the size of an empty Empire State Building, compared with 10.7% for central London, according to data provided by UBS.

Bonds for Canary Wharf Group—the company that owns most of the buildings in the area—are trading at a deep discount, with yields over 16%. Moody’s lowered its credit rating to junk last month.

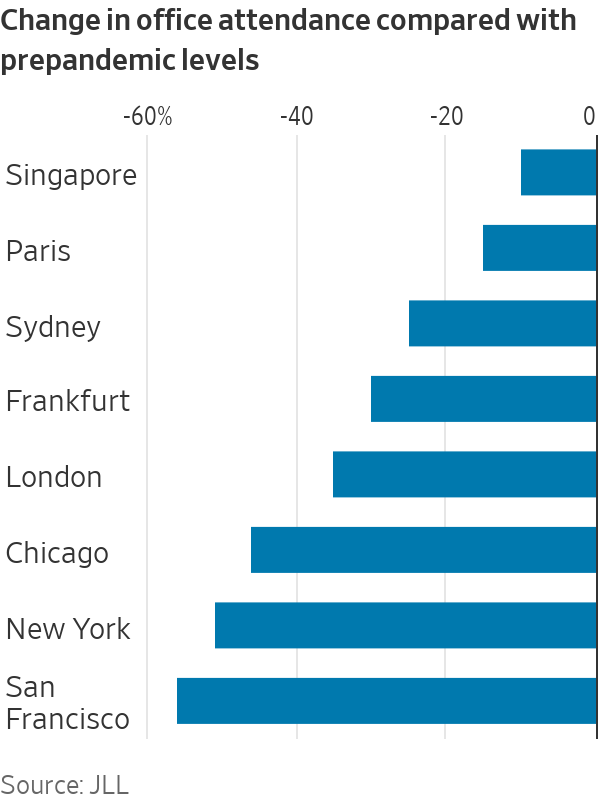

The troubles at Canary Wharf show how the rapid rise of remote work has reverberated unevenly across global property markets. While the hollowing out of skyscrapers has become a familiar theme in U.S. cities since the pandemic, Europe’s office market has held up relatively well, as workers have been far more eager to return to the office.

But London has some problems that are familiar to American real estate.

The return-to-office rate for London stood at 65% in February, a figure that put it between New York City, which stood at 49%, and Paris, which was at 85%, according to JLL, a property-services company.

Canary Wharf has caught the brunt of the problems in London’s office market.

Work-from-home and the cost of upgrading old office space to meet environmental regulations “puts Canary Wharf at a disadvantage,” said Zachary Gauge, head of European real-estate research at UBS.

Canary Wharf was a byproduct of a changing London economy in the 1980s. Transformations in global shipping decimated the city’s sprawling blue-collar dockyards, the West India Docks. Margaret Thatcher’s government deregulated the financial industry in a move known as the “big bang,” and banks were hungry for towers that were larger than low-slung London’s standard fare.

While it wasn’t a great property investment—the original developer went bankrupt—skyscrapers sprouted through the 1990s and Canary Wharf became a rare slice of Manhattan in London.

Canary Wharf attracted tenants from London’s traditional financial district, known as the City of London, which lies several miles west. It became a global byword for urban renewal. Former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg made it his go-to analogy when promoting plans for Hudson Yards in the late 2000s.

“Canary Wharf beat out the City in the 1990s and 2000s because it catered to American firms who wanted high-rise buildings for high-skilled labor,” said Anthony Breach, an analyst at the Centre for Cities, a think tank.

A generation later, its towers are far from new, while sleek modern skyscrapers have shot up in the buzzier streets of the City and other parts of central London.

“High rates of work from home means that employers need to offer some desirability and vibrancy to bring workers back,” said Marie Dormeuil, an analyst at Green Street, a commercial-real-estate advisory firm.

Top-end commercial-property rents in London’s more fashionable West End rose 8% a year over the past three years, buoyed by hedge funds and private-equity firms piling into Georgian townhouses, while rents in Canary Wharf have mostly stayed the same, according to Green Street. Average office-space rent in Canary Wharf is $69 a square foot, compared with $95 in the City and more than $165 in the West End, according to data from Knight Frank, a U.K. real-estate brokerage.

With most of the district held by Canary Wharf Group—a joint venture between Qatar’s wealth fund and private-equity giant Brookfield—or by the Qatari fund directly, the development has space for long-term planning. “The Canary Wharf Group is very good at making its own weather,” said Tony Travers, who directs the London School of Economics’ London centre.

Shobi Khan, Canary Wharf Group’s chief executive, has outlined a plan for a “Canary Wharf 3.0” that would thrive off of residential rents, entertainment offerings and biotech.

The group plans to construct a 750,000-square-foot life-sciences centre, which it says will be the largest commercial lab in Europe. Rents in the sector can bring in a 70% premium compared with office space, according to Savills, a British real-estate-services company.

As for the residential sector, 3,500 people inhabit the group’s 2,200 units there, compared with zero tenants three years ago. Two thousand more units are under construction.

A combination of high-end retailers, restaurants and music and arts festivals have brought in extra revenue. Foot traffic on evenings and weekends is up by 50% compared with pre pandemic levels, according to data from the city’s transport authority.

But a full makeover will be a difficult task to pull off. Higher interest rates and lower revenue mean that Qatar and Brookfield may need to put up more cash to cover the costs of refurbishment and construction.

Another risk: Fewer financiers and lawyers could mean little demand for the stores and amenities. “You could see a downward spiral as people start to leave,” said Breach, the think tank analyst.

The developers will likely need to lure in lots of people like Justin Walker, a tax accountant who works in JPMorgan Chase’s office there.

“I hated how sterile Canary Wharf looked when I first got here,” he said, “But, the place has grown on me, it’s more residential now, and a lot more vibrant.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

As Paris makes its final preparations for the Olympic games, its residents are busy with their own—packing their suitcases, confirming their reservations, and getting out of town.

Worried about the hordes of crowds and overall chaos the Olympics could bring, Parisians are fleeing the city in droves and inundating resort cities around the country. Hotels and holiday rentals in some of France’s most popular vacation destinations—from the French Riviera in the south to the beaches of Normandy in the north—say they are expecting massive crowds this year in advance of the Olympics. The games will run from July 26-Aug. 1.

“It’s already a major holiday season for us, and beyond that, we have the Olympics,” says Stéphane Personeni, general manager of the Lily of the Valley hotel in Saint Tropez. “People began booking early this year.”

Personeni’s hotel typically has no issues filling its rooms each summer—by May of each year, the luxury hotel typically finds itself completely booked out for the months of July and August. But this year, the 53-room hotel began filling up for summer reservations in February.

“We told our regular guests that everything—hotels, apartments, villas—are going to be hard to find this summer,” Personeni says. His neighbours around Saint Tropez say they’re similarly booked up.

As of March, the online marketplace Gens de Confiance (“Trusted People”), saw a 50% increase in reservations from Parisians seeking vacation rentals outside the capital during the Olympics.

Already, August is a popular vacation time for the French. With a minimum of five weeks of vacation mandated by law, many decide to take the entire month off, renting out villas in beachside destinations for longer periods.

But beyond the typical August travel, the Olympics are having a real impact, says Bertille Marchal, a spokesperson for Gens de Confiance.

“We’ve seen nearly three times more reservations for the dates of the Olympics than the following two weeks,” Marchal says. “The increase is definitely linked to the Olympic Games.”

Getty Images

According to the site, the most sought-out vacation destinations are Morbihan and Loire-Atlantique, a seaside region in the northwest; le Var, a coastal area within the southeast of France along the Côte d’Azur; and the island of Corsica in the Mediterranean.

Meanwhile, the Olympics haven’t necessarily been a boon to foreign tourism in the country. Many tourists who might have otherwise come to France are avoiding it this year in favour of other European capitals. In Paris, demand for stays at high-end hotels has collapsed, with bookings down 50% in July compared to last year, according to UMIH Prestige, which represents hotels charging at least €800 ($865) a night for rooms.

Earlier this year, high-end restaurants and concierges said the Olympics might even be an opportunity to score a hard-get-seat at the city’s fine dining.

In the Occitanie region in southwest France, the overall number of reservations this summer hasn’t changed much from last year, says Vincent Gare, president of the regional tourism committee there.

“But looking further at the numbers, we do see an increase in the clientele coming from the Paris region,” Gare told Le Figaro, noting that the increase in reservations has fallen directly on the dates of the Olympic games.

Michel Barré, a retiree living in Paris’s Le Marais neighbourhood, is one of those opting for the beach rather than the opening ceremony. In January, he booked a stay in Normandy for two weeks.

“Even though it’s a major European capital, Paris is still a small city—it’s a massive effort to host all of these events,” Barré says. “The Olympics are going to be a mess.”

More than anything, he just wants some calm after an event-filled summer in Paris, which just before the Olympics experienced the drama of a snap election called by Macron.

“It’s been a hectic summer here,” he says.

AFP via Getty Images

Parisians—Barré included—feel that the city, by over-catering to its tourists, is driving out many residents.

Parts of the Seine—usually one of the most popular summertime hangout spots —have been closed off for weeks as the city installs bleachers and Olympics signage. In certain neighbourhoods, residents will need to scan a QR code with police to access their own apartments. And from the Olympics to Sept. 8, Paris is nearly doubling the price of transit tickets from €2.15 to €4 per ride.

The city’s clear willingness to capitalise on its tourists has motivated some residents to do the same. In March, the number of active Airbnb listings in Paris reached an all-time high as hosts rushed to list their apartments. Listings grew 40% from the same time last year, according to the company.

With their regular clients taking off, Parisian restaurants and merchants are complaining that business is down.

“Are there any Parisians left in Paris?” Alaine Fontaine, president of the restaurant industry association, told the radio station Franceinfo on Sunday. “For the last three weeks, there haven’t been any here.”

Still, for all the talk of those leaving, there are plenty who have decided to stick around.

Jay Swanson, an American expat and YouTuber, can’t imagine leaving during the Olympics—he secured his tickets to see ping pong and volleyball last year. He’s also less concerned about the crowds and road closures than others, having just put together a series of videos explaining how to navigate Paris during the games.

“It’s been 100 years since the Games came to Paris; when else will we get a chance to host the world like this?” Swanson says. “So many Parisians are leaving and tourism is down, so not only will it be quiet but the only people left will be here for a party.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.