America Had ‘Quiet Quitting.’ In China, Young People Are ‘Letting It Rot.’

Demoralized by a weak economy and unfulfilling jobs, young Chinese are dropping out, exploring spirituality and becoming more rebellious, presenting new challenges for Beijing

China’s ruling Communist Party wants the country’s young people to be ambitious, work hard and prepare for adversity.

Li Jiajia just wants to win the lottery.

Demoralised by a weak economy, unfulfilling jobs and a paternalistic state, young Chinese such as Li are looking for pathways out of the carefully scripted lives their elders want for them, putting themselves at odds with the country’s priorities.

After moving to Beijing from her hometown in southeastern China in April, the 24-year-old Li found her new job as a content creator at a technology startup uninspiring. She said she has no desire to climb the corporate ladder, especially when the number of high-paying Chinese tech jobs is shrinking.

The ever-present role of the state in daily life is stultifying, she said. Though she wanted to be a journalist in high school, she gave up when she realised how heavily the government censors the media.

She says she knows she probably won’t win the lottery. But when she plays, at least she can dream of a better life—most likely abroad.

“I want to leave here and live the life I want,” Li said. “It won’t happen overnight, but for now, the thrill of scratching lottery tickets gives me a little break.”

Since China’s government cracked down on disaffected students in Tiananmen Square in 1989, most young people, who came of age in an era of rapid economic growth and rising affluence, have done what they are supposed to do—and been rewarded for it.

They studied diligently to get into prestigious universities, clocked gruelling hours at fast-growing companies and followed traditional expectations of career and family, riding China’s boom to material success.

Many are still doing that. But a growing number of middle-class urbanites in their 20s and 30s in China have begun to question that trajectory, if not reject it entirely, as prospects of upward mobility fade.

More than two years of harsh government Covid controls left some pondering the role of the Communist Party and other sources of authority in their lives, or even the meaning of life and who they aspire to be—questions many had never contemplated before.

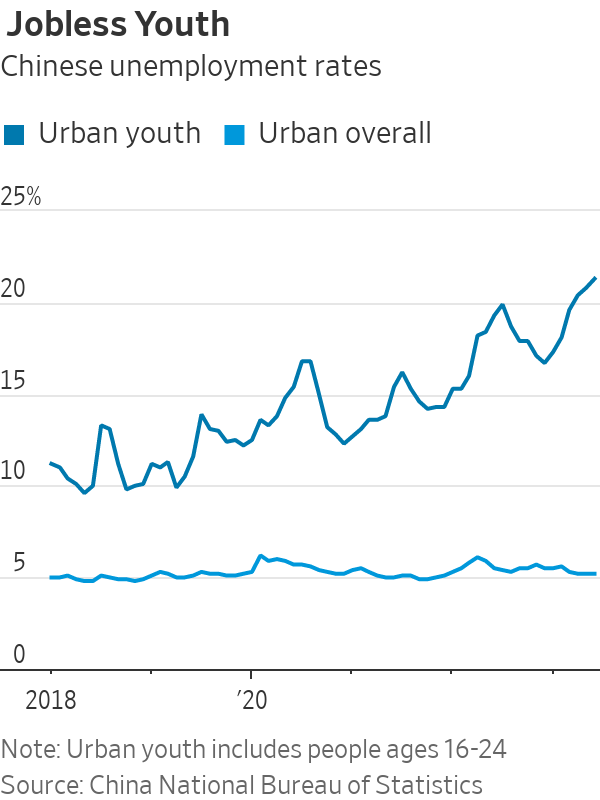

Record youth unemployment that topped 21% this year has further dented confidence in traditional paths to achievement in China. Some, like Li, are also frustrated about other issues, such as violence against women in China or government efforts to prevent people from accessing foreign apps such as Twitter or Instagram.

Many are quitting their jobs and turning to meditation and other forms of spirituality. Some are moving far from China’s megacities to start lives anew in places like Dali, a southwestern city famous within China as a hub for digital nomads and dropouts.

Others are flooding fortune-teller stands and Buddhist temples in mountainous areas, or exploring Chinese and Western philosophers and writers from Laozi to Hermann Hesse. Some are throwing “quitting parties” with banners celebrating their newfound freedom.

“This generation has had a lot of resources invested in them,” said Sara Friedman, professor of anthropology and gender studies at Indiana University, who studies Chinese society.

“They have worked really hard. They have been pushed really hard. And to then say, ‘I’m stepping out of this rat race, I’m opting out,’ is a pretty radical decision to be making.”

From ‘lying flat’ to ‘letting it rot’

Social-media discussions about temple visits and anxiety—a central preoccupation of many young Chinese—have surged in 2023, according to BigOne Lab, a research firm.

About 34% of surveyed respondents in their mid-20s quit or were considering resigning from jobs in China’s consumer internet sector—a major employer of young people—in the first half of 2023, according to China’s job-seeking and social platform Maimai.

Playing the lottery has become especially trendy for 20- and 30-somethings, whose purchases of lottery tickets helped push sales to $67 billion from January to October, a 53% jump from the previous year and averaging $48 per person in China.

Catchphrases describing the mood have worked their way into everyday discourse. First, in 2020, was the arcane sociological term neijuan, or “involution,” which referred to situations in which people work hard and compete without anyone getting ahead.

That was followed by “touching fish.” The phrase, borrowed from a Chinese idiom, referred to executing small rebellions at work, such as taking long toilet breaks, doing online shopping or reading novels in the office.

Next was “lying flat,” a form of mundane resistance that involves dragging one’s feet at work or dropping out of the workforce altogether. Last year, the phrase “let it rot” spread to describe young people who have completely given up.

A survey conducted by Tsingyan Group, a research firm, last year found that approximately 96% of nearly 6,000 respondents in China were aware of people “lying flat” to various degrees in their vicinity. The concept held more appeal among people ages 26 to 40 than other Chinese, the survey showed.

“It’s a very passive form of resistance,” said Silvia Lindtner, an ethnographer at the University of Michigan. “It’s definitely a very difficult moment, but it could also be seen as a hopeful moment where there is pressure, in some ways, on the leadership.”

Echoes of the 1960s

In some ways the ennui resembles the “quiet quitting” phenomenon of post pandemic America—or, going back further, the rejection of social norms by young people across the Western world in the 1960s.

In those days, two decades of fast economic growth and wider affluence gave young people more choices than previous generations. Many responded by challenging their parents’ way of life.

In China, where open protests are rarely possible, young people are now rebelling in other ways.

“Lying flat is a latent resistance to the moral blackmailing of society,” said Amy Yan, a 27-year-old Shenzhen resident who once worked as a buyer for her family’s export business. When the business went bankrupt last year after her parents lost their assets in a financial scam, it reinforced her belief that she should give priority to her spirituality.

Even before the bankruptcy, she had decided that accepting the corporate grind and meeting traditional expectations of marriage and children would interfere with her desire to explore her spirituality.

Following the family crisis, she put her savings of $27,000 into supporting a tiny Taoist ashram she had started with a few fellow practitioners.

Coming into Beijing’s crosshairs

Communist Party leaders have long worried young people could stir unrest, as they did in 1989. The party needs young people to get on board with Beijing’s priorities, not just to keep the economy humming and avoid instability, but to help make China stronger in an era of great-power competition with the U.S.

In a speech at last year’s Communist Party congress, widely quoted in Chinese media, leader Xi Jinping laid out his vision for young people, urging them to have “ideals, courage, a willingness to endure hardship and a dedication to strive” to help “build a modernised socialist country.”

In a 2021 article published in the top party journal Qiushi, he specifically warned against “lying flat.” Discussions of the phenomenon have often triggered censorship online.

If all the young people who had dropped out of China’s labor force and relied financially on their parents were counted, China’s real youth unemployment rate could be as high as 46.5%, according to calculations earlier this year by a Peking University professor.

The Communist Party Youth League—with more than 70 million members—has published commentary on its official WeChat account criticising college graduates for having too much pride. Job seekers “should not refuse to enter the workforce due to the difficulty of finding a job or choose to ‘lie flat’ out of fear of ‘involution,’” the article read.

Greater affluence—but an uncertain future

Until recently, China’s economic progress seemed to be unstoppable, with per-capita incomes surging to around $13,000 in 2022 from less than $1,000 in 2000, according to the World Bank.

But economic growth has slowed. Many economists worry China could get stuck in the “middle-income trap,” in which a country’s progress plateaus before it gets rich. Per-capita incomes in the U.S. were around $76,000 last year.

Academic research shows that social mobility for many groups in China has stalled, meaning it has become harder for people without connections to get ahead.

Many employers that young people gravitated to, including Alibaba, Tencent and ByteDance, have been shedding staff amid weak growth and government clampdowns on the private sector. Tech salaries have declined in the past three years, according to Maimai, and opportunities for initial public offering payouts have faded, leaving many who used to work “996” schedules—9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week—wondering what the point was.

It is also true that many more middle-class young people—especially those without children and mortgages—can afford to drop out of the rat race today than in previous eras.

Some plan to leave: Net emigration from China, which fell to 125,000 in 2012 as the country’s economy boomed, rebounded to more than 310,000 in the first 11 months of 2023, according to United Nations data.

Others want to stay—but on their own terms.

Huang Xialu quit her high-stress job as a product manager at one of China’s largest video-streaming companies in April, so she could focus more on spiritual retreats. For a long time before that, the 33-year-old said she had struggled with a lack of purpose.

“I had a very urgent sense that if I didn’t listen to my gut and take a break to explore what I truly wanted to do in this world, it would be too late,” she said.

In the months following Huang’s resignation, she traveled to Dali, where she worked on a tarot-reading stand, took a training course in life coaching and learned to make pottery.

To Huang, lying flat is the opposite of being passive—it is a path for taking control of one’s own life when wading through uncertain terrain, she said.

Now she has become a certified life coach, helping individuals who are as confused as she was to find a way forward. Her income is less stable.

But “I haven’t regretted quitting for a second,” she said.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Relationships get complicated when one spouse retires and the other keeps working

When one spouse retires but the other doesn’t, roles change and feelings get complicated.

David Buck, 60, stepped back from a long career in sales management just as his wife, Susan Rose, 58, an ordained minister, leaned in, working 40-plus hours a week.

They’ve had to rethink who does what at home. David now folds more of the laundry and takes on grocery duties. He also has freedom, which Susan sometimes longs for. He talks about going to visit their adult children, who live out of state. Their first grandchild is on the way.

“I do get jealous. I have a couple more years,” Susan says.

Most couples now retire at di’fferent times , research suggests.

Only 18% of retired households claimed Social Security at the same time, according to a review of Federal Reserve data conducted by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

A separate poll found that just 11% of couples retire at the same time. Nearly two-thirds stagger their retirement by at least a year, according to a survey of 1,510 couples ages 45 to 70 commissioned by Ameriprise Financial, a financial services company.

Timing two retirements

The timing of retirement is often out of a couple’s hands. Nearly one-third of retirees surveyed left the workforce unexpectedly due to layoffs and early retirement packages. Health is also a factor.

Women, who often leave work to care for older parents or in-laws, retire at younger ages, averaging 62 compared with 65 for men, according to the Center for Retirement Research. A younger spouse may continue working to keep family health insurance until Medicare kicks in, or to delay having to tap retirement savings. They may want to hold off collecting Social Security to get higher payments.

Some people simply want to keep working even if their partner doesn’t. Living on one paycheck can be scary for people used to having two, no matter how much money couples have.

When couples retire at different times, routines, schedules and expectations diverge, and tensions can surface. Assumptions arise over who should clean or make dinner. The still-working partner may feel a twinge of envy when the other one heads to the beach or visits grandchildren.

“There can be resentment. This is the time people have been dreaming about,” says Pepper Schwartz, emeritus professor of sociology at the University of Washington who focuses on relationships.

Other couples are wary of their partner retiring and being around all the time. “They dread too much togetherness,” says working filmmaker Sharon Hyman, 61, who lives separately from her retired partner of 25 years.

Navigating new routines

David Brown, 70, and Beth Keenan-Brown, 64, planned to retire together. Last year, Beth left her nursing job and David retired from the Secret Service. They made plans to travel to Budapest and spend more time at their beach house.

Shortly after Beth retired, she received a dream job offer and returned to work full time, as director of clinical operations for a Maryland hospice agency. Now she spends the week in their Severna Park, Md., home, which is larger and has space for a home office, while David stays at their beach home in Delaware, where he bikes and volunteers with Meals on Wheels. They travel back and forth.

“It’s a challenge keeping our calendars straight,” says David.

Beth logs her meetings on a joint Google Calendar so David knows when not to call. Every morning, they FaceTime over coffee and talk about their plans. On Wednesdays they each get takeout from the same type of restaurant, recently Ethiopian, and eat together over a video call.

There are upsides, too. They have made two trips since she took her new job, one to Costa Rica and the other to the Netherlands, thanks to her added income. Beth has unlimited paid vacation with her new job.

She says it would be hard if they were still in the same house and she was working while he was retired. “I think I would drive you nuts,” says Beth, adding that she is younger and has more energy than David.

“I just can’t keep up with you,” says David, who had a stroke a few years ago and needed to slow down.

Tough choices, new roles

Jeni Mastin, 74, of Vancouver, British Columbia, retired a decade ago from a career in nonprofits and social work. Her partner, Cameron Hood, is still working as a musician, teaching music and performing jazz.

“I’m an artist. I imagine I will be working until I drop dead,” he says.

Their different schedules and responsibilities have led to some inconveniences. Earlier this year, Jeni planned a monthlong 65th birthday celebration for Cameron in Mexico. They cut it a week short because of his teaching job. Cameron’s work schedule also means that he can’t always go with Jeni to her doctor’s appointments. His substitute teaching job ends at 3:30 p.m. and there’s an hourlong commute.

David Buck and his wife, Susan Rose, the minister, are navigating the transition in Ponte Vedra Beach, Fla.

David, who describes himself as “semiretired,” continues to advise some clients of his time-management consulting business. Susan logs more than 40 hours a week doing two part-time jobs, one as transitional pastor at a local church and the other at a nonprofit she formed to mentor women in ministry.

David has picked up more responsibilities at home, taking on tasks that Susan did before she began working more and he semiretired. He takes their cars in for maintenance and balances the checkbook.

“If the dogs need to go to the vet, that’s me,” says David.

Susan says she has a hard time letting some things go. “I will say, ‘I can go to the grocery store on the way home,’ and Dave will say, ‘Stop. I can go to the grocery store. Tell me what we need,’ ” she says, although he tends to pick up snacks and cookies that she wouldn’t buy.

It has been an adjustment for David, too.

Being semiretired, he says he sometimes forgets about the demands of a job, especially one in ministry where congregation members have needs outside of 9 to 5. She might call and say her meeting went longer than expected. “Then I’m sitting there thinking, ‘I got dinner about ready. What am I going to do now?’ ” he says.

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Consumers are going to gravitate toward applications powered by the buzzy new technology, analyst Michael Wolf predicts