Why Introverted Leaders Are Ideal for the Post pandemic Workplace

As an extrovert, I hate to admit it, but charisma really doesn’t improve a firm’s performance

Leigh Thompson is the J. Jay Gerber Professor of Dispute Resolution and Organizations and a director of executive-education programs at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management. She is the author of several books, including “Negotiating the Sweet Spot: The Art of Leaving Nothing on the Table.”

I’m an extrovert and I admit I’ve benefited from it.

Outgoing people are more likely to be noticed, selected as leaders and awarded “halo” traits—meaning that other people just assume extroverts are more likeable, intelligent and have other positive qualities. But as a social scientist, I can’t ignore the research: Most of these beliefs about extroverts simply aren’t true.

Studies show that introverts and extroverts are equally effective in academic and corporate environments, and that there is no actual relation between CEO charisma and firm performance.

Yet the misconceptions about extroverts persist, making them more likely to be chosen as leaders over their more introverted peers. That’s unfortunate because in our post pandemic world, replete with remote work, hybrid communication, far-flung team members, artificial intelligence and global disruption, introverts are particularly well-equipped to lead.

That may be hard to believe because of two persistent myths.

First is the widely held stereotype that effective leaders are gregarious, alpha and comfortable in the spotlight, even craving that attention. In reality, the social skills that extroverts display aren’t necessarily predictive of capable leadership.

Second is the belief that quieter people lack leadership skills. They are seen as less social, unassertive, sad and disconnected. Indeed, in a recent study in which people in different groups were instructed to “act like an extrovert” or “act like an introvert” regardless of their actual personalities, those who acted extroverted were disproportionately selected for leadership. And, interestingly, those who pretended to be introverted in that study reported feeling sad.

Both of these myths ignore the reality that introversion, far from being simply a lack of extroversion, is a distinct set of traits with its own large merits. This was true well before the pandemic, but the remote-work environment illuminated the bias even more and highlighted the need to change our perceptions.

Here are five reasons why introverts could be ideal leaders in the redefined workplace.

1. Remote-work performance. Extroverts’ job performance declined when the pandemic forced many businesses to go remote. A study of remote workers found that extroverted employees became less productive, less engaged and less satisfied with their jobs. A separate study found that team average extroversion had a large negative effective on team performance—that is, the more extroverted the team members were as a group, the worse they performed.

2. Dealing with adversity and change. Introverts show a greater capacity to engage, think through and make wise choices during periods of adversity and change. A recent investigation found that introverts had more positive attitudes toward AI and using AI overall than did extroverts. A separate study found that during periods of high conflict, extroverts develop fewer energising relationships with their teammates and aren’t viewed as proactively contributing to the team. Introverts, however, often possess a predisposition for things like empathy and thoughtful communication—all critical for navigating team dynamics and conflict in tough times.

3. Creativity. Introverts’ creativity flows well in the quiet aftermath of group interactions, positioning them as formidable leaders for innovative and reflective tasks. In studies of communication and conflict, introverts’ tendency to think before speaking was seen to yield more creative solutions.

4. Avoiding avoidance. Most humans approach positive things and avoid negative things. Sounds like a good policy—unless we’re talking about workplace challenges. Research has shown that extroverts commit more passive avoidance errors—that is, when the going gets tough, they tend to avoid the situation altogether; meanwhile introverts are more likely to inspect the half-empty glass or the disappointing customer-satisfaction data, generating insights and solutions.

5. Resilience against quitting. A study of over 200 people revealed a correlation between extroversion and burnout—that is, the more extroverted a person reported themselves to be, the more likely they were to burn out. Introversion, on the other hand, was uncorrelated with burnout, suggesting better immunity.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

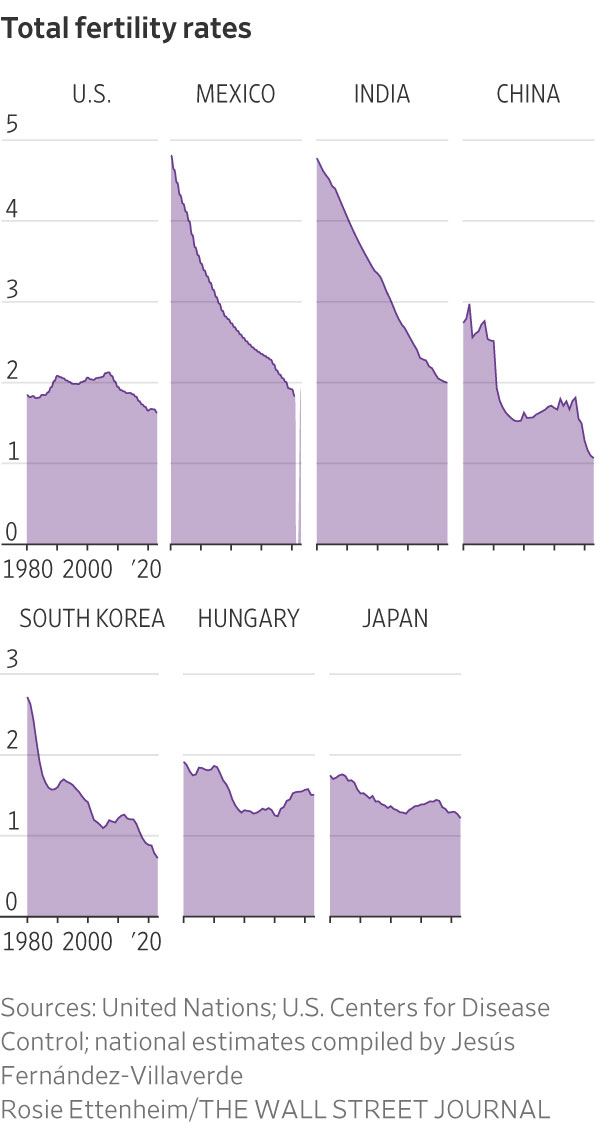

Birthrates are falling fast across countries, with economic, social and geopolitical consequences

The world is at a startling demographic milestone. Sometime soon, the global fertility rate will drop below the point needed to keep population constant. It may have already happened.

Fertility is falling almost everywhere, for women across all levels of income, education and labor-force participation. The falling birthrates come with huge implications for the way people live, how economies grow and the standings of the world’s superpowers.

In high-income nations, fertility fell below replacement in the 1970s, and took a leg down during the pandemic. It’s dropping in developing countries, too. India surpassed China as the most populous country last year, yet its fertility is now below replacement.

“The demographic winter is coming,” said Jesús Fernández-Villaverde, an economist specialising in demographics at the University of Pennsylvania.

Many government leaders see this as a matter of national urgency. They worry about shrinking workforces , slowing economic growth and underfunded pensions; and the vitality of a society with ever-fewer children. Smaller populations come with diminished global clout, raising questions in the U.S., China and Russia about their long-term standings as superpowers.

Some demographers think the world’s population could start shrinking within four decades—one of the few times it’s happened in history.

Donald Trump , this year’s presumptive Republican presidential nominee, has called collapsing fertility a bigger threat to Western civilization than Russia. A year ago Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida declared that the collapse of the country’s birthrate left it “standing on the verge of whether we can continue to function as a society.” Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni has prioritized raising the country’s “demographic GDP.”

Governments have rolled out programs to stop the decline—but so far they’ve barely made a dent.

Demographic surprise

In 2017, when the global fertility rate—a snapshot of how many babies a woman is expected to have over her lifetime—was 2.5, the United Nations thought it would slip to 2.4 in the late 2020s. Yet by 2021, the U.N. concluded, it was already down to 2.3—close to what demographers consider the global replacement rate of about 2.2. The replacement rate, which keeps population stable over time, is 2.1 in rich countries, and slightly higher in developing countries, where fewer girls than boys are born and more mothers die during their childbearing years.

While the U.N. has yet to publish estimated fertility rates for 2022 and 2023, Fernández-Villaverde has produced his own estimate by supplementing U.N. projections with actual data for those years covering roughly half the world’s population. He has found that national birth registries are typically reporting births 10% to 20% below what the U.N. projected.

China reported 9 million births last year , 16% less than projected in the U.N.’s central scenario. In the U.S., 3.59 million babies were born last year, 4% less than the U.N. projected. In other countries, the undershoot is even larger: Egypt reported 17% fewer births last year. In 2022, Kenya reported 18% fewer.

Fernández-Villaverde estimates global fertility fell to between 2.1 and 2.2 last year, which he said would be below global replacement for the first time in human history. Dean Spears, a population economist at the University of Texas at Austin, said while the data isn’t good enough to know precisely when or if fertility has fallen below replacement, “we have enough evidence to be quite confident about…the crossing point not being far off.”

In 2017 the U.N. projected world population, then 7.6 billion, would keep climbing to 11.2 billion in 2100. By 2022 it had lowered and brought forward the peak to 10.4 billion in the 2080s. That, too, is likely out of date. The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington now thinks it will peak around 9.5 billion in 2061 then start declining.

In the U.S., a short-lived pandemic baby boomlet has reversed. The total fertility rate fell to 1.62 last year, according to provisional government figures, the lowest on record .

Had fertility stayed near 2.1, where it stood in 2007, the U.S. would have welcomed an estimated 10.6 million more babies since, according to Kenneth Johnson, senior demographer at the University of New Hampshire.

In 2017, when the fertility rate was 1.8, the Census Bureau projected it would converge over the long run to 2.0. It has since revised that down to 1.5. “It has snuck up on us,” said Melissa Kearney, an economist at the University of Maryland specialising in demographics.

A second demographic transition?

Historians refer to the decline in fertility that began in the 18th century in industrialising countries as the demographic transition. As lifespans lengthened and more children survived to adulthood, the impetus for bearing more children declined. As women became better educated and joined the workforce, they delayed marriage and childbirth, resulting in fewer children.

Now, said Spears, “the big-picture fact is that birthrates are low or are falling in many diverse societies and economies.”

Some demographers see this as part of a “second demographic transition,” a society-wide reorientation toward individualism that puts less emphasis on marriage and parenthood, and makes fewer or no children more acceptable.

In the U.S., some thought at first that women were simply delaying childbirth because of lingering economic uncertainty from the 2008 financial crisis.

In research published in 2021 , the University of Maryland’s Kearney and two co-authors looked for possible explanations for the continued drop. They found that state-level differences in parental abortion notification laws, unemployment, Medicaid availability, housing costs, contraceptive usage, religiosity, child-care costs and student debt could explain almost none of the decline. “We suspect that this shift reflects broad societal changes that are hard to measure or quantify,” they conclude.

Kearney said while raising children is no more expensive than before, parents’ preferences and perceived constraints have changed: “If people have a preference for spending time building a career, on leisure, relationships outside the home, that’s more likely to come in conflict with childbearing.”

Meanwhile, time-use data show that mothers and fathers, especially those that are highly educated, spend more time with their children than in the past. “The intensity of parenting is a constraint,” Kearney said.

Erica Pittman, a 45-year-old business banker in Raleigh, N.C., said she and her husband opted to have only one child because of demands on their time, including caring for her mother, who died last year after a long battle with multiple sclerosis. Their 8-year-old son is able to participate in theatre workshops, soccer and summer camps because the couple, with a combined income of about $225,000 a year, has more time and money.

“I feel like a better mom,” Pittman said. “I feel like I can go to work—because I have a fairly demanding job—but I can also make time to volunteer at his school, be the chaperone for the field trip and do those kinds of things, because I only have one to coordinate with my schedule.”

Pittman said she only questions their decision when her son says he wishes he had a sibling to play with. In response, she and her husband, a middle-school history teacher, pick vacation destinations with a kids’ club, such as a Disney cruise, so her son can play with others his age.

‘Plugged into the global culture’

Fertility is below replacement in India even though the country is still poor and many women don’t work —factors that usually sustain fertility.

Urbanisation and the internet have given even women in traditional male-dominated villages a glimpse of societies where fewer children and a higher quality of life are the norm. “People are plugged into the global culture,” said Richard Jackson, president of the Global Aging Institute, a nonprofit research and education group.

Mae Mariyam Thomas, 38, who lives in Mumbai and runs an audio production company, said she’s opted against having children because she never felt the tug of motherhood. She sees peers struggling to meet the right person, getting married later and, in some instances, divorcing before they have kids. At least three of her friends have frozen their eggs, she said.

“I think now we live in a really different world, so I think for anyone in the world it’s tough to find a partner,” she said.

Sub-Saharan Africa once appeared resistant to the global slide in fertility, but that too is changing. The share of all women of reproductive age using modern contraception grew from 17% in 2012 to 23% in 2022, according to Family Planning 2030, an international organisation.

Jose Rimon, a professor of public health at Johns Hopkins University, credits that to a push by national leaders in Africa which, he predicted, would drive fertility down faster than the U.N. projects.

Once a low fertility cycle kicks in, it effectively resets a society’s norms and is thus hard to break, said Jackson. “The fewer children you see your colleagues and peers and neighbours having, it changes the whole social climate,” he said.

Danielle Vermeer grew up third in a family of four children on Chicago’s North Side, where her neighbourhood was filled with Catholics of Italian, Irish and Polish descent and half her close friends had as many siblings as her or more. Her Italian-American father was one of four children who produced 14 grandchildren. Now her parents have five grandchildren, including Vermeer’s two children, ages 4 and 7.

The 35-year-old, who is the co-founder of a fashion thrifting app, said that before setting out to have children, she consulted dozens of other couples and her Catholic church and read at least eight books on the subject, including one by Pope Paul VI. She and her husband settled on two as the right number.

“The act of bringing a child into this world is an incredible responsibility,” she said.

New policies

Governments have tried to reverse the fall in fertility with pro natalist policies.

Perhaps no country has been trying longer than Japan. After fertility fell to 1.5 in the early 1990s, the government rolled out a succession of plans that included parental leave and subsidised child care. Fertility kept falling.

In 2005, Kuniko Inoguchi was appointed the country’s first minister responsible for gender equality and birthrate. The main obstacle, she declared, was money: People couldn’t afford to get married or have children. Japan made hospital maternity care free and introduced a stipend paid upon birth of the child.

Japan’s fertility rate climbed from 1.26 in 2005 to 1.45 in 2015. But then it started declining again, and in 2022 was back to 1.26.

This year, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida rolled out yet another program to increase births that extends monthly allowances to all children under 18 regardless of income, free college for families with three children, and fully paid parental leave.

Inoguchi, now a member of parliament’s upper house, said the constraint on would-be parents is no longer money, but time. She has pressed the government and businesses to adopt a four-day workweek. She said, “If you’re a government official or manager of a big corporation, you should not worry over questions of salary now, but that in 20 years time you will have no customers, no clients, no applicants to the Self-Defense Forces.”

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban has pushed one of Europe’s most ambitious natality agendas. Last year he expanded tax benefits for mothers so that women under the age of 30 who have a child are exempt from paying personal income tax for life. That’s on top of housing and child-care subsidies as well as generous maternity leaves.

Hungary’s fertility rate, though still well below replacement, has risen since 2010. But the Vienna Institute of Demography attributed this primarily to women delaying childbirth because of a debt crisis that hit around 2010. Adjusted for that, fertility has risen only slightly, it concluded.

In the U.S., while state and federal legislators have pushed to expand child-care subsidies and parental leave, they have generally not set a higher birthrate as an explicit goal. Some Republicans, though, are leaning in that direction. Last year, Trump said he backed paying out “baby bonuses” to prop up U.S. births, and GOP Arizona Senate candidate Kari Lake recently endorsed the idea.

Republican Sen. J.D. Vance of Ohio said falling fertility matters beyond the economic pressures of a smaller labor force and unfunded Social Security. “Do you live in communities where there are smiling happy children, or where people are just ageing?” he said in an interview. Lack of siblings and cousins, he said, contributes to children’s social isolation.

He’s studied potential solutions, in particular Hungary’s approach, but hasn’t seen proof of anything that works over the long term.

The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation found little evidence that pronatalist policies lead to sustained rebounds in fertility. A woman may get pregnant sooner to capture a baby bonus, researchers say, but likely won’t have more kids over the course of her lifetime.

Economic pressure

With no reversal in birthrates in sight, the attendant economic pressures are intensifying. Since the pandemic, labor shortages have become endemic throughout developed countries. That will only worsen in coming years as the postcrisis fall in birthrates yields an ever-shrinking inflow of young workers, placing more strain on healthcare and retirement systems.

Neil Howe , a demographer at Hedgeye Risk Management, has pointed to a recent World Bank report suggesting that worsening demographics could make this a second consecutive “lost decade” for global economic growth.

The usual prescription in advanced countries is more immigration, but that has two problems. As more countries confront stagnant population, immigration between them is a zero-sum game. Historically, host countries have sought skilled migrants who enter through formal, legal channels, but recent inflows have been predominantly unskilled migrants often entering illegally and claiming asylum.

High levels of immigration have also historically aroused political resistance, often over concerns about cultural and demographic change. A shrinking native-born population is likely to intensify such concerns. Many of the leaders keenest to raise birthrates are most resistant to immigration.

As birthrates fall, more regions and communities experience depopulation, with consequences ranging from closed schools to stagnant property values. Less selective colleges will soon struggle to fill classrooms because of the plunge in birthrates that began in 2007, said Fernández-Villaverde. Vance said rural hospitals can’t stay open because of the falling local population.

An economy with fewer children will struggle to finance pensions and healthcare for growing ranks of elderly. South Korea’s national pension fund, one of the world’s largest, is on track to be depleted by 2055. A special legislative committee recently presented several possible pension reforms, but there’s only a short window to act before the next presidential election campaign heats up.

There’s been little public pressure to act, said Sok Chul Hong, an economist at Seoul National University. “The elderly are not very interested in pension reform, and the youth are apathetic towards politics,” he said. “It is truly an ironic situation.”

Consumers are going to gravitate toward applications powered by the buzzy new technology, analyst Michael Wolf predicts

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan