Cruise Lines Pursue Greener Journeys Ahead of New Climate Rules

As tourists flock to ships and strain port cities, companies are pushed to invest in cleaner tech

AMSTERDAM—The global cruise industry is trying to go green ahead of a wave of new climate rules. Getting it done involves managing high costs, a dearth of renewable fuel and pressure from regulators and environmental groups.

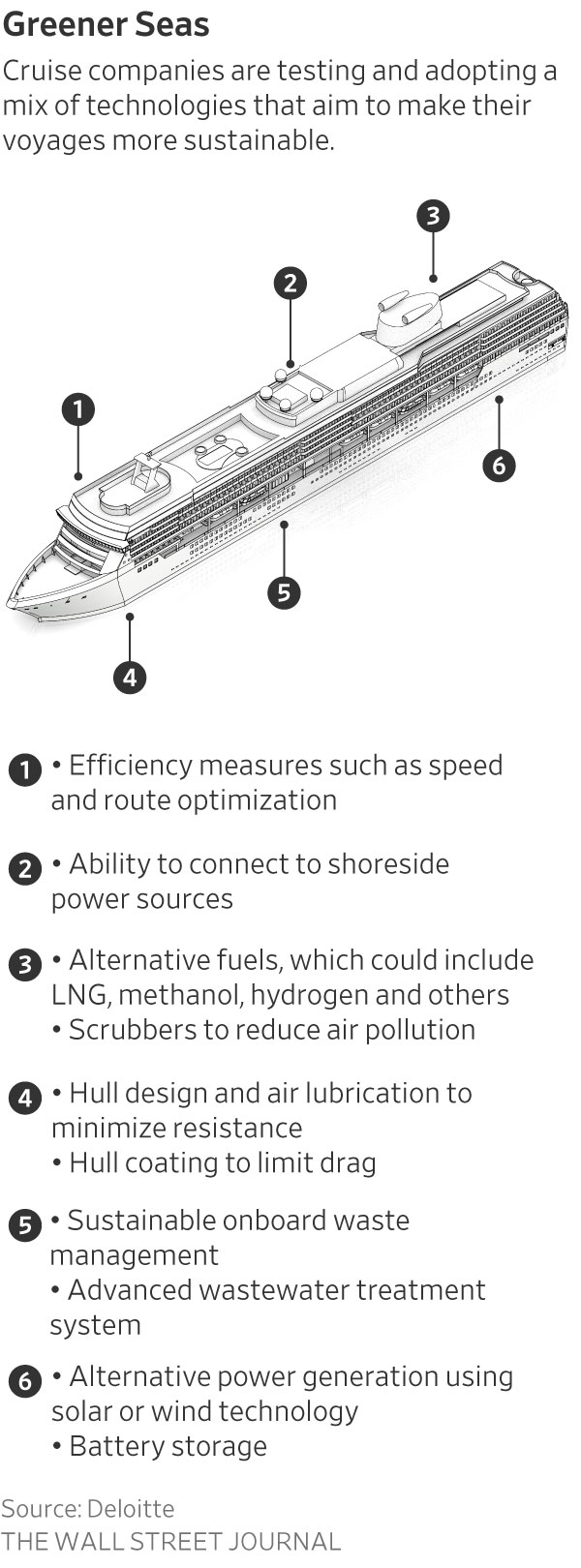

Cruise operators are buying new ships that can run on alternative fuels, redesigning hulls to move more efficiently through the water and adding electricity hookups for when their ships are at port, where they otherwise might pump out toxic exhaust.

Carnival, the world’s biggest cruise company, has equipped more than half of its fleet to plug into local power grids when docked. Royal Caribbean and Norwegian Cruise Line Holdings have ships on order that the companies say will be able to run on methanol. MSC Cruises uses a digital platform to analyse weather, fuel consumption and other data to optimise its ships’ efficiency.

The companies are preparing for new rules that will require them to pay for some of their emissions and meet new targets in transitioning to cleaner fuels. They also expect that global regulations could tighten further. Cruise lines, like other parts of the shipping industry, are pushed to act quickly and thoroughly because ships that are ordered today are likely to be in operation for decades.

“We build ships now that last 40 years,” said Torstein Hagen, chairman of cruise company Viking, which has ships on order that will be equipped to use renewable hydrogen. “We’d better get it right.”

Complicating the industry’s investments is the high cost of building and fuelling eco-friendly ships after some cruise operators racked up billions of dollars in debt during the pandemic. Cleaner renewable fuels are expensive and aren’t yet available or used in large quantities. Just 34 of the world’s ocean-cruise ports—roughly 2%—have electrical hookups, according to industry figures.

The number of passengers taking oceangoing cruises is expected to jump this year to more than 31 million, according to industry group Cruise Lines International Association, up from about 20 million last year and about 6% above 2019 levels, before the pandemic largely shut down the industry.

That revival has put renewed pressure on port cities, as some seek limits on visits by cruise ships, and added to concerns from environmentalists about the industry’s contribution to global greenhouse gas emissions.

Although cruise ships are responsible for a tiny portion of overall human-caused greenhouse-gas emissions, their onboard services contribute to higher emissions on average compared with cargo ships, according to industry estimates.

Cruises are also discretionary—nobody must go on a cruise—a point that environmentalists raise in their calls for fast action from the industry.

Faig Abbasov, director for shipping at environmental group Transport & Environment, said some cruise companies are investing in technology that can sharply reduce their emissions once it is in use—such as hydrogen fuel cells or engines that can run on green methanol—but the overall industry isn’t moving quickly enough.

New environmental rules are set to take effect over the coming years.

Shipping companies whose vessels start or end voyages in Europe, including those that run large cruise ships, will have to start paying for a portion of their emissions beginning next year through the EU’s emissions-trading system. A separate EU law will compel shipping companies to progressively increase their use of lower-emission fuels beginning in 2025, and ports in the bloc that are used frequently by cruise and containerships will need to provide onshore electricity connections by 2030.

California already has state-level rules that require cruise ships to plug into shore power or otherwise sharply curb their emissions while at high-traffic ports including Los Angeles and Long Beach.

And the International Maritime Organization, a United Nations organisation, in July committed to new greenhouse-gas emission reduction targets. The IMO also has rules for energy efficiency and carbon intensity in the shipping industry.

Regulations are “the only way that you can seriously drive this kind of massive step change in what we’re doing as an industry,” said Linden Coppell, MSC Cruises’ vice president for sustainability. Incoming rules will affect the kinds of ships the company orders in the future, how it transitions to alternative fuels and efforts to improve the vessels’ efficiency, she said.

Cruise companies are moving ahead with green investments despite the debt that some of them racked up during the pandemic.

Carnival said it has fewer new ships on order than at any point in recent decades. However, the company said it hasn’t significantly reduced capital expenditures, which include investments in sustainability-related technologies. Royal Caribbean said its sustainability commitments remained steadfast during the pandemic.

Norwegian has indicated in earnings reports that compliance with environmental rules and its own climate commitments will be costly. The company announced plans for two new methanol-ready ships earlier this year.

The biggest cruise companies “have tremendous access to capital and continue to invest in sustainable technologies,” said Ivan Feinseth, director of research and analyst at Tigress Financial Partners.

Not every move to alternative technology is winning fans. LNG emits less carbon dioxide and significantly fewer air pollutants than the heavy fuel oil used in many ships. But environmental groups say any climate benefits are overshadowed by the escape of unburned methane, a potent contributor to global warming, into the atmosphere.

“LNG is the best thing out there today,” said William Burke, Carnival’s chief maritime officer and a retired vice admiral with the U.S. Navy. He said ships that are built to use LNG will also be capable of running on bio or synthetic forms of the fuel in the future.

Carnival is working with manufacturers to reduce the release of methane and will have more efficient engines in newer ships, he said.

Green methanol, which can be produced from biomass or by using renewable electricity, is gaining ground as a viable alternative fuel for the shipping industry, in part because it can be stored at room temperature.

Norwegian expects to take delivery of two methanol-ready ships in 2027 and 2028. Mark Kempa, the company’s chief financial officer, acknowledged on an earnings call earlier this year that the ships would cost more, but added, “going green is not free.”

Privately owned cruise company Viking, which has a fleet of 10 ocean vessels, says it sees renewable hydrogen as the best future fuel. The company ordered ships that can run on both hydrogen and traditional marine fuels, and its Viking Neptune vessel has hydrogen fuel cells on board to test out the technology. But supplies of the fuel are still limited.

“We can’t solve the world’s hydrogen supply problem,” Hagen said. He said the company plans to increase its use of the fuel as it becomes more available. “When that happens, then we are prepared.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

As Paris makes its final preparations for the Olympic games, its residents are busy with their own—packing their suitcases, confirming their reservations, and getting out of town.

Worried about the hordes of crowds and overall chaos the Olympics could bring, Parisians are fleeing the city in droves and inundating resort cities around the country. Hotels and holiday rentals in some of France’s most popular vacation destinations—from the French Riviera in the south to the beaches of Normandy in the north—say they are expecting massive crowds this year in advance of the Olympics. The games will run from July 26-Aug. 1.

“It’s already a major holiday season for us, and beyond that, we have the Olympics,” says Stéphane Personeni, general manager of the Lily of the Valley hotel in Saint Tropez. “People began booking early this year.”

Personeni’s hotel typically has no issues filling its rooms each summer—by May of each year, the luxury hotel typically finds itself completely booked out for the months of July and August. But this year, the 53-room hotel began filling up for summer reservations in February.

“We told our regular guests that everything—hotels, apartments, villas—are going to be hard to find this summer,” Personeni says. His neighbours around Saint Tropez say they’re similarly booked up.

As of March, the online marketplace Gens de Confiance (“Trusted People”), saw a 50% increase in reservations from Parisians seeking vacation rentals outside the capital during the Olympics.

Already, August is a popular vacation time for the French. With a minimum of five weeks of vacation mandated by law, many decide to take the entire month off, renting out villas in beachside destinations for longer periods.

But beyond the typical August travel, the Olympics are having a real impact, says Bertille Marchal, a spokesperson for Gens de Confiance.

“We’ve seen nearly three times more reservations for the dates of the Olympics than the following two weeks,” Marchal says. “The increase is definitely linked to the Olympic Games.”

Getty Images

According to the site, the most sought-out vacation destinations are Morbihan and Loire-Atlantique, a seaside region in the northwest; le Var, a coastal area within the southeast of France along the Côte d’Azur; and the island of Corsica in the Mediterranean.

Meanwhile, the Olympics haven’t necessarily been a boon to foreign tourism in the country. Many tourists who might have otherwise come to France are avoiding it this year in favour of other European capitals. In Paris, demand for stays at high-end hotels has collapsed, with bookings down 50% in July compared to last year, according to UMIH Prestige, which represents hotels charging at least €800 ($865) a night for rooms.

Earlier this year, high-end restaurants and concierges said the Olympics might even be an opportunity to score a hard-get-seat at the city’s fine dining.

In the Occitanie region in southwest France, the overall number of reservations this summer hasn’t changed much from last year, says Vincent Gare, president of the regional tourism committee there.

“But looking further at the numbers, we do see an increase in the clientele coming from the Paris region,” Gare told Le Figaro, noting that the increase in reservations has fallen directly on the dates of the Olympic games.

Michel Barré, a retiree living in Paris’s Le Marais neighbourhood, is one of those opting for the beach rather than the opening ceremony. In January, he booked a stay in Normandy for two weeks.

“Even though it’s a major European capital, Paris is still a small city—it’s a massive effort to host all of these events,” Barré says. “The Olympics are going to be a mess.”

More than anything, he just wants some calm after an event-filled summer in Paris, which just before the Olympics experienced the drama of a snap election called by Macron.

“It’s been a hectic summer here,” he says.

AFP via Getty Images

Parisians—Barré included—feel that the city, by over-catering to its tourists, is driving out many residents.

Parts of the Seine—usually one of the most popular summertime hangout spots —have been closed off for weeks as the city installs bleachers and Olympics signage. In certain neighbourhoods, residents will need to scan a QR code with police to access their own apartments. And from the Olympics to Sept. 8, Paris is nearly doubling the price of transit tickets from €2.15 to €4 per ride.

The city’s clear willingness to capitalise on its tourists has motivated some residents to do the same. In March, the number of active Airbnb listings in Paris reached an all-time high as hosts rushed to list their apartments. Listings grew 40% from the same time last year, according to the company.

With their regular clients taking off, Parisian restaurants and merchants are complaining that business is down.

“Are there any Parisians left in Paris?” Alaine Fontaine, president of the restaurant industry association, told the radio station Franceinfo on Sunday. “For the last three weeks, there haven’t been any here.”

Still, for all the talk of those leaving, there are plenty who have decided to stick around.

Jay Swanson, an American expat and YouTuber, can’t imagine leaving during the Olympics—he secured his tickets to see ping pong and volleyball last year. He’s also less concerned about the crowds and road closures than others, having just put together a series of videos explaining how to navigate Paris during the games.

“It’s been 100 years since the Games came to Paris; when else will we get a chance to host the world like this?” Swanson says. “So many Parisians are leaving and tourism is down, so not only will it be quiet but the only people left will be here for a party.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.