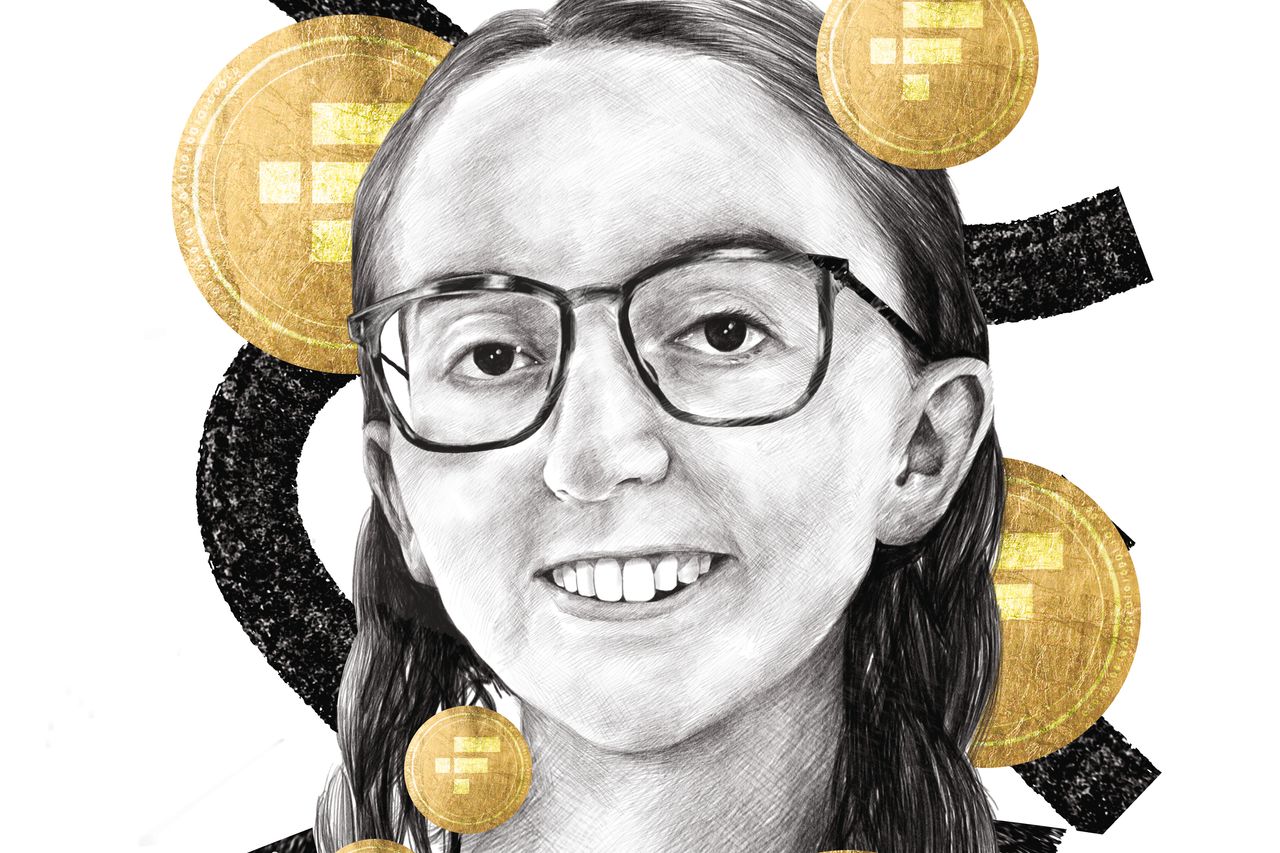

How Caroline Ellison Found Herself at the Centre of the FTX Crypto Collapse

As CEO of Alameda Research, Ms. Ellison took a leading role in helping Sam Bankman-Fried build the FTX empire

On a video call in early November, employees at Alameda Research dialled in to learn the fate of the trading firm, which was teetering on the brink.

It was up to Caroline Ellison to deliver the bad news. Alameda was at the centre of Sam Bankman-Fried‘s collapsing FTX empire. Ms. Ellison, who had just turned 28, was at the centre of Alameda. And they were all in crisis.

Alameda and crypto exchange FTX were both the brainchild of Ms. Ellison’s friend Mr. Bankman-Fried, and he had picked her to help lead Alameda the year before. For a time, they rode the crypto wave together, with FTX eventually notching a blockbuster valuation of $32 billion. This month, it all came crashing down in a matter of days.

Customers had grown fearful about the companies’ financial health, yanking their money from FTX in a short, frenzied period. The firms scrambled to stay afloat, but they filed for bankruptcy shortly after Ms. Ellison’s call with employees. Mr. Bankman-Fried resigned as FTX’s chief executive.

Prosecutors, regulators and even FTX’s new CEO are investigating what happened. Customers are losing hope they will ever see their money again. Lawsuits have followed, and many top employees have left. Ms. Ellison has been fired along with Gary Wang and Nishad Singh. They were also top deputies of Mr. Bankman-Fried’s.

Before the crash, Mr. Bankman-Fried hugged the spotlight, promoting crypto and lobbying for its interests in Washington, while Ms. Ellison remained in the engine room. Alameda, a trading firm owned almost entirely by Mr. Bankman-Fried, had one overarching purpose: Make money. Ms. Ellison was tasked with keeping it running.

In a handful of podcasts and other public appearances, Ms. Ellison was quick to summarise her rapid ascent as almost accidental. She joined Wall Street straight from graduating Stanford University in 2016, though the move was less a calling than an answer to the question she found herself asking in college: What are math majors supposed to do with their lives, anyway?

It was at her first job, at the quant-trading powerhouse Jane Street Capital, that she met another 20-something trader, Mr. Bankman-Fried. Like her, he had been raised by two professors. Like her, he spoke highly of a movement called “effective altruism,” or the idea of making big money to give away.

When Mr. Bankman-Fried left to start Alameda, Ms. Ellison soon followed in what she called “a blind leap into the unknown.” She was still barely out of college—but she was also one of the more experienced traders there, she said in an FTX podcast in 2020.

Caroline Ellison grew up in the Boston suburbs, the daughter of two MIT economists. At 5, she read the second “Harry Potter” book to herself, she said on the podcast. At 8, she wrote an analysis of stuffed-animal prices, according to Forbes. Her father, inspired by his daughters, wrote advanced-math textbooks for children bored by basic lessons.

She and Messrs. Bankman-Fried, Wang and Singh comprised the board of what they called the Future Fund, with the goal of making grants to nonprofits and investments in “socially impactful companies.” Critics say the effective altruism worldview can encourage excessive risk-taking—since people can always argue that bigger paydays lead to bigger donations.

Messrs. Bankman-Fried, Wang and Singh all owned stakes in at least some of the FTX companies, according to a filing in bankruptcy court by the new CEO.

At times, Ms. Ellison and Mr. Bankman-Fried were romantically involved, The Wall Street Journal previously reported.

When Ms. Ellison arrived at Alameda, she was surprised at how it made even fast-paced Jane Street look slow. “It was like, wow, the process for doing things is just someone suggests something and then someone codes it up and releases it,” she said in the FTX podcast. “An hour later and it’s already happened.”

Everything in Mr. Bankman-Fried’s orbit seemed to move at the same breakneck speed. He launched an Alameda sister firm, FTX, in 2019, and it took just a few years for it to become one of the biggest crypto exchanges in the world. For a while, Mr. Bankman-Fried was CEO of both companies.

Use of stimulants was common among his upper echelon, the Journal previously reported.

“Nothing like regular amphetamine use to make you appreciate how dumb a lot of normal, non-medicated human experience is,” Ms. Ellison tweeted last year.

Alameda and FTX had employees in both Hong Kong and the Bahamas. Ms. Ellison, like Mr. Bankman-Fried, had recently been working from the Bahamas much of the time, according to a person familiar with the matter.

Among Alameda’s trading strategies was arbitrage—buying a coin in one location and selling it elsewhere for more. FTX, meanwhile, emerged as a key marketplace for investors large and small to buy and sell crypto. As a major player in digital currencies, Alameda traded frequently on FTX’s platform.

Around 2020, Alameda began “yield farming,” investing in tokens that pay interest-rate-like rewards. At first, Ms. Ellison pushed back. In an FTX podcast in early 2021, she recalled arguing about whether the firm should engage, and said she had concerns about the riskiness. “I lost that argument,” she said in the podcast.

Over time, Alameda’s aggressive trading strategies relied more on intuition and indicators like Elon Musk’s social-media posts, according to tweets in 2021 by Sam Trabucco, then another rising star at Alameda.

By fall 2021, cryptocurrency prices were approaching their all-time high and FTX was celebrating its recent deal for the naming rights of the University of California, Berkeley’s football stadium. Mr. Bankman-Fried named Ms. Ellison and Mr. Trabucco as co-CEOs to run Alameda so he could focus on FTX. They inherited a 25-person operation, according to Alameda’s press release at the time.

Though Mr. Bankman-Fried was no longer CEO, Alameda was still his company, too. According to FTX’s bankruptcy filings, he owned 90% of the trading firm. Mr. Wang owned the other 10%.

By early 2022, digital currencies were in free fall. Many of the industry’s biggest investment and lending firms began to buckle, then give way. As panic swept through the crypto world, Mr. Bankman-Fried sought to appear as a rescuer, buying out some troubled firms and extending credit to others to help stabilise the market.

Behind the scenes, though, Alameda was far from immune from the shakeout. Mr. Bankman-Fried’s vaunted trading firm was getting margin calls, too.

In August of this year, Mr. Trabucco said he was stepping down as co-CEO. In a lengthy Twitter thread, he said working at Alameda had been “difficult and exhausting and consuming.”

By early November, the spotlight that Mr. Bankman-Fried so often courted began to reveal his companies’ troubles. A CoinDesk report raised concerns about the financial health of Alameda and FTX. Changpeng Zhao, head of rival exchange Binance, tweeted that his firm would dump its holdings of FTT as a risk-management move. FTT is a digital currency of FTX.

As Mr. Zhao and Mr. Bankman-Fried sparred over Twitter, Ms. Ellison tried to cool the fire. “If you’re looking to minimise the market impact on your FTT sales, Alameda will happily buy it all from you today at $22!” she tweeted, tagging Mr. Zhao. A few minutes before, FTT had traded around $22.15, according to CoinDesk data.

When asked on Twitter why Ms. Ellison had made the offer, Mr. Bankman-Fried replied, “I mean that’s up to her to answer, but they said they were worried about impact which this would solve for them, and this is just quicker and easier.” Binance contacted her about the offer but never heard back, the Journal reported.

Ultimately, the close ties between Alameda and FTX were their undoing. FTX used customer money to lend billions of dollars to Alameda for risky trades and investments, according to previous reporting by the Journal. In traditional finance, regulators require brokerages to segregate customer funds from any capital they use for trading.

In the video meeting in early November, held late in the evening Hong Kong time, Ms. Ellison told employees that FTX used customer money to help Alameda meet its liabilities, the Journal previously reported. She apologised and said that she had disappointed the staff, the Journal reported. By then, the companies’ financial problems had spilled into public view, but the companies hadn’t yet filed for bankruptcy,

Ms. Ellison also told employees that she, Messrs. Bankman-Fried, Singh and Wang were aware of the decision to send customer money to Alameda.

Many Alameda employees quit the next day, the Journal reported.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

As Paris makes its final preparations for the Olympic games, its residents are busy with their own—packing their suitcases, confirming their reservations, and getting out of town.

Worried about the hordes of crowds and overall chaos the Olympics could bring, Parisians are fleeing the city in droves and inundating resort cities around the country. Hotels and holiday rentals in some of France’s most popular vacation destinations—from the French Riviera in the south to the beaches of Normandy in the north—say they are expecting massive crowds this year in advance of the Olympics. The games will run from July 26-Aug. 1.

“It’s already a major holiday season for us, and beyond that, we have the Olympics,” says Stéphane Personeni, general manager of the Lily of the Valley hotel in Saint Tropez. “People began booking early this year.”

Personeni’s hotel typically has no issues filling its rooms each summer—by May of each year, the luxury hotel typically finds itself completely booked out for the months of July and August. But this year, the 53-room hotel began filling up for summer reservations in February.

“We told our regular guests that everything—hotels, apartments, villas—are going to be hard to find this summer,” Personeni says. His neighbours around Saint Tropez say they’re similarly booked up.

As of March, the online marketplace Gens de Confiance (“Trusted People”), saw a 50% increase in reservations from Parisians seeking vacation rentals outside the capital during the Olympics.

Already, August is a popular vacation time for the French. With a minimum of five weeks of vacation mandated by law, many decide to take the entire month off, renting out villas in beachside destinations for longer periods.

But beyond the typical August travel, the Olympics are having a real impact, says Bertille Marchal, a spokesperson for Gens de Confiance.

“We’ve seen nearly three times more reservations for the dates of the Olympics than the following two weeks,” Marchal says. “The increase is definitely linked to the Olympic Games.”

Getty Images

According to the site, the most sought-out vacation destinations are Morbihan and Loire-Atlantique, a seaside region in the northwest; le Var, a coastal area within the southeast of France along the Côte d’Azur; and the island of Corsica in the Mediterranean.

Meanwhile, the Olympics haven’t necessarily been a boon to foreign tourism in the country. Many tourists who might have otherwise come to France are avoiding it this year in favour of other European capitals. In Paris, demand for stays at high-end hotels has collapsed, with bookings down 50% in July compared to last year, according to UMIH Prestige, which represents hotels charging at least €800 ($865) a night for rooms.

Earlier this year, high-end restaurants and concierges said the Olympics might even be an opportunity to score a hard-get-seat at the city’s fine dining.

In the Occitanie region in southwest France, the overall number of reservations this summer hasn’t changed much from last year, says Vincent Gare, president of the regional tourism committee there.

“But looking further at the numbers, we do see an increase in the clientele coming from the Paris region,” Gare told Le Figaro, noting that the increase in reservations has fallen directly on the dates of the Olympic games.

Michel Barré, a retiree living in Paris’s Le Marais neighbourhood, is one of those opting for the beach rather than the opening ceremony. In January, he booked a stay in Normandy for two weeks.

“Even though it’s a major European capital, Paris is still a small city—it’s a massive effort to host all of these events,” Barré says. “The Olympics are going to be a mess.”

More than anything, he just wants some calm after an event-filled summer in Paris, which just before the Olympics experienced the drama of a snap election called by Macron.

“It’s been a hectic summer here,” he says.

AFP via Getty Images

Parisians—Barré included—feel that the city, by over-catering to its tourists, is driving out many residents.

Parts of the Seine—usually one of the most popular summertime hangout spots —have been closed off for weeks as the city installs bleachers and Olympics signage. In certain neighbourhoods, residents will need to scan a QR code with police to access their own apartments. And from the Olympics to Sept. 8, Paris is nearly doubling the price of transit tickets from €2.15 to €4 per ride.

The city’s clear willingness to capitalise on its tourists has motivated some residents to do the same. In March, the number of active Airbnb listings in Paris reached an all-time high as hosts rushed to list their apartments. Listings grew 40% from the same time last year, according to the company.

With their regular clients taking off, Parisian restaurants and merchants are complaining that business is down.

“Are there any Parisians left in Paris?” Alaine Fontaine, president of the restaurant industry association, told the radio station Franceinfo on Sunday. “For the last three weeks, there haven’t been any here.”

Still, for all the talk of those leaving, there are plenty who have decided to stick around.

Jay Swanson, an American expat and YouTuber, can’t imagine leaving during the Olympics—he secured his tickets to see ping pong and volleyball last year. He’s also less concerned about the crowds and road closures than others, having just put together a series of videos explaining how to navigate Paris during the games.

“It’s been 100 years since the Games came to Paris; when else will we get a chance to host the world like this?” Swanson says. “So many Parisians are leaving and tourism is down, so not only will it be quiet but the only people left will be here for a party.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.