Millennials Are Coming for Your Golf Communities

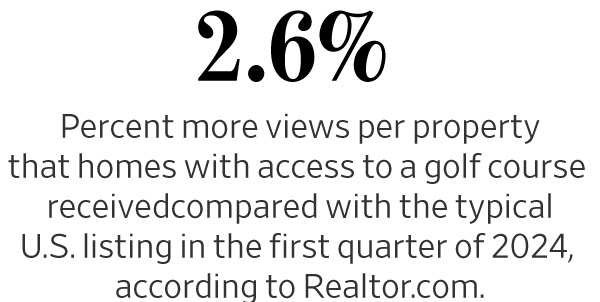

Living on golf courses has surged in popularity since the pandemic. Many courses have upgraded facilities and broadened amenities. Now the 40-year-olds want in too.

Gabrielle Sloan, 30, and her husband, Brandon Sloan, 30, never thought they’d live on a golf course. Gabrielle doesn’t even play golf—yet, at least.

But in January 2020, the Sloans spent $660,000 to buy a three-bedroom, roughly 1,960-square-foot ranch house on approximately 0.25 acres that backs up to the course at Tequesta Country Club, a private golf club in Tequesta, Fla., a village on Palm Beach County’s northern border.

“We loved how family-friendly the neighbourhood is,” says Gabrielle, noting that the club is catering to a younger crowd. “That lifestyle is something we wanted.”

Across the U.S., millennials like the Sloans are moving to where the grass is greener: private golf communities. “Millennials are starting to solidify their lives,” says Cindy Scholz, a real-estate broker with Compass in New York City and the Hamptons, on New York’s Long Island. “And they are strategically using real estate to shape their lifestyles.”

In Texas, about 10 miles west of downtown Austin is Barton Creek, a community where the Barton Creek Country Club is a selling point. “Before the pandemic, millennials were sporadically buying in Barton Creek,” says Stephanie Nick, a Douglas Elliman sales agent. “Now it’s a full-bore, ‘let’s get going on the country club lifestyle’ movement.”

In Barton Creek, Nick says millennial house hunters typically budget about $3 million to $4 million. In 2023, she sold a millennial a four-bedroom, 5,500-square-foot house for $3.5 million. Recently, she showed a $5 million house to a young couple with one child.

Nick believes millennials—born between 1981 and 1996—are tired of paying more for less in the city. In Austin, $3 million might buy a roughly 3,000-square-foot house on a small parcel, she says, whereas that same price in Barton Creek might buy a 5,000-square-foot to 6,000-square-foot house on a half to one acre in a community with easy access to four 18-hole golf courses, tennis, workout facilities, swimming and more.

In Georgia, Mary Catherine Smith, a real estate agent with Corcoran Classic Living, says millennials are moving to Jennings Mill Country Club, less than five miles south of downtown Athens. In March, Smith listed a typical Jennings Mill property—a five bedroom, 4,984 square foot house on 1.07 acres—for $965,000.

One reason Smith thinks young homeowners gravitate to the club is for its social life. “Many Jennings Mills residents have golf carts,” she says. “They’ll trolley around together on the weekend.”

“There are millennials who have never picked up a golf club, and a country club neighbourhood is still the only place they want to be,” says Byron Wood, a real estate agent with Sotheby’s International Realty – Westlake Village Brokerage, about 10 miles from Los Angeles’s city limits.

Millennials moving to private golf communities is a trend that might have seemed unthinkable before the Covid pandemic, when such enclaves seemed destined for the rough due to waning interest in the sport, especially among young people.

Then an unlikely coincidence occurred.

Golf play surged during the pandemic and continues to grow: In 2023, more golf rounds were played than any other year on record, according to the National Golf Foundation.

Meanwhile, since the Great Recession, there are private golf clubs that have been transforming themselves into amenity-rich lifestyle hubs, whose resort-style pools, sports facilities, fitness centres, dining and social programming have broad appeal, says Jason Becker, co-founder and CEO of Golf Life Navigators, an online platform that connects golfers to golf clubs and golf communities across the U.S.

At the same time, during the pandemic, millennials started turning 40 years old. Research from Club Benchmarking, a private golf club business intelligence firm, shows that the average age of new private golf club joiners is early 40s, says Michael J. Timmerman, the company’s chief market intelligence officer.

That means at the same time golf and private golf clubs came back into style, the next generation of Muffys and Skips were primed to start their country club years.

Consequently, the NGF has seen a shift toward younger private golf club members on the heels of the pandemic. Since 2019, the number of golfers at private golf clubs has increased by approximately 25%, from just under 1.5 million to 1.9 million, according to the NGF. Adults under the age of 50 comprise 60% of those memberships, with young adults, ages 18 to 34, representing about 30%. The latter can include adult children of members, typically up to a certain age.

There is no one-size-fits-all U.S private golf club community. Some clubs have housing within their gates; other clubs are integrated within regular residential neighbourhoods. Roughly speaking, a top-tier club’s golf initiation fee could be $250,000 or much more, with annual dues in the mid-tens of thousands and up. However, there are also clubs with golf initiation fees and annual dues in the low thousands or less. Typically, there are lower-priced membership options that don’t include golf, such as social or pool- and tennis-only memberships.

In December 2021, Tyson Hawley, 37, and his wife, Maital Hawley, 40, paid $1.15 million for a turnkey four bedroom, 4,272 square foot house on 0.4 acres backing up to the golf course at the Bermuda Dunes Country Club. It’s located in California’s greater Palm Springs area, which has more than 110 golf courses, of which more than half are private.

“I leave my house and I’m on my club’s first tee in two minutes,” Tyson Hawley says. Hawley is a real estate agent with Desert Sotheby’s International Realty. He says within a prestigious desert club’s gates, houses might be in the multi-millions. However, there are lower priced golf community options that work for his millennial buyers, who typically have house budgets of about $800,000 to $1.2 million, he says.

undefined “It is very possible to buy a house at $350 per square foot in a golf community and be super pumped about what you get for your membership,” he says. “There are clubs that understand that millennials are in a season of their lives where they can’t hang with the big dogs paying $250,000 for an initiation fee.”

Golf Life Navigators’s Jason Becker says some private clubs have invested in their amenities, golf course and branding, while others have not and rely upon their historic status. “Millennials are very cautious by nature in terms of their finances and investments,” Becker says. “Industry officials are seeing very in-depth questions coming from millennials pertaining to the club’s financial health and long-term plan to remain healthy.”

Becker says there are, of course, golf communities where there aren’t many younger members, specifically those in the U.S.’s Southeast or Southwest that are geared toward retirees or second-home owners. “There’s just so much demand from the baby boomers,” says Becker, noting that since the pandemic, generally speaking, membership wait lists are now lengthy, fees associated with being a member are up, attrition rates are down and tee time availability is compressed. He added that the cost of being a member at some clubs can be prohibitive for younger people, especially in an era when the average initiation fee at a private club has increased 50% to 70% since 2021. In the Sunbelt, the average age of private golf club searchers is between ages 55 to 57, according to Golf Life Navigators’s data.

That’s not a hard-and-fast rule, though. In the Phoenix area, Lisa Roberts is a real-estate agent with Russ Lyon Sotheby’s International Realty. She is working with a young millennial couple at McCormick Ranch Golf Club, in Scottsdale. They recently went into contract for $1.1 million on a three bedroom, 2,550 square foot house on 0.21 acre. “They plan to upgrade once they have children and a more established income,” Roberts says, “but this house lets them lay a foundation within the club’s gates now.”

Becker says whether younger people will be battling generational stereotypes hinges on the club’s culture, which sets the tone for all members. “It is up to the club’s board and management team to lead the way of established culture, such as playing music on the golf course or wearing a hat in the clubhouse,” Becker says. “For younger, new members, the club’s culture has to be understood or frustration will likely surface.”

Club Benchmarking’s Michael J. Timmerman says, “It really depends on how the club is designed, whether the club wants to focus on programming that will attract different members.” Timmerman adds that clubs catering to younger members and families will develop social programming specifically tailored to that age group.

Around the communities of Monterey and Carmel on California’s Central Coast, there are storied golf courses including the public Pebble Beach Golf Links and the private Monterey Peninsula Country Club. Nic Canning, managing partner at Canning Properties Group with Sotheby’s International Realty – Carmel Brokerage, says retirees and second-home owners typically live around these premiere courses, where he says properties can range from roughly $15 million to $35 million around Pebble Beach, and $3 million to $10 million around MPCC.

However, the area is rich with golf—there are roughly a dozen public courses and a half-dozen private clubs—and Canning has seen an influx of millennials buying in family-friendly private golf communities such as the Club at Pasadera, Santa Lucia Preserve and Tehama Golf Club, and the semi-private Carmel Valley Ranch. He says since the pandemic, the area has particularly attracted tech workers migrating from Silicon Valley, with San Jose being only about 70 miles north.

At these clubs, Canning has recently sold millennials properties such as a three bedroom, 2,717-square-foot house on approximately 0.23 acres for $3.792 million, and a house with roughly similar specs for $2.7 million. Another house that has three bedrooms and 4,396 square feet on 13.3 acres just sold to a millennial for $4.42 million.

“Millennials are less driven by ocean views and care more about the community, the school district and access to things like restaurants, grocery shopping, trails and beaches,” Canning says.

Similarly, millennials want to equip their private golf-club houses a certain way. Kate O’Hara, CEO and creative director of O’Hara Interiors, which is based in Minneapolis and Austin, says the country club houses her firm works on might include everything from golf-simulator rooms and yoga studios, to outdoor-access showers and expanded mudrooms for equipment storage.

Back in Tequesta, Fla., the Sloans spent about $150,000 to optimise their house to fit their lifestyle, including adding durable furnishings and built-in cabinetry and jazzing up their outdoor entertaining area. They did so with the help of local interior designer Victoria Meadows Murphy, 35, who has a knack for taking the Bob Hope vibes out of country club homes without losing the martini spirit.

Meadows Murphy and her husband, Evan Murphy, 35, are building their own house, a project budgeted at $2.8 million, on a tear-down lot on the Sloans’s same golf course. “It’s exciting seeing the turnover of houses as young people are moving in,” Meadows Murphy says.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

As Paris makes its final preparations for the Olympic games, its residents are busy with their own—packing their suitcases, confirming their reservations, and getting out of town.

Worried about the hordes of crowds and overall chaos the Olympics could bring, Parisians are fleeing the city in droves and inundating resort cities around the country. Hotels and holiday rentals in some of France’s most popular vacation destinations—from the French Riviera in the south to the beaches of Normandy in the north—say they are expecting massive crowds this year in advance of the Olympics. The games will run from July 26-Aug. 1.

“It’s already a major holiday season for us, and beyond that, we have the Olympics,” says Stéphane Personeni, general manager of the Lily of the Valley hotel in Saint Tropez. “People began booking early this year.”

Personeni’s hotel typically has no issues filling its rooms each summer—by May of each year, the luxury hotel typically finds itself completely booked out for the months of July and August. But this year, the 53-room hotel began filling up for summer reservations in February.

“We told our regular guests that everything—hotels, apartments, villas—are going to be hard to find this summer,” Personeni says. His neighbours around Saint Tropez say they’re similarly booked up.

As of March, the online marketplace Gens de Confiance (“Trusted People”), saw a 50% increase in reservations from Parisians seeking vacation rentals outside the capital during the Olympics.

Already, August is a popular vacation time for the French. With a minimum of five weeks of vacation mandated by law, many decide to take the entire month off, renting out villas in beachside destinations for longer periods.

But beyond the typical August travel, the Olympics are having a real impact, says Bertille Marchal, a spokesperson for Gens de Confiance.

“We’ve seen nearly three times more reservations for the dates of the Olympics than the following two weeks,” Marchal says. “The increase is definitely linked to the Olympic Games.”

Getty Images

According to the site, the most sought-out vacation destinations are Morbihan and Loire-Atlantique, a seaside region in the northwest; le Var, a coastal area within the southeast of France along the Côte d’Azur; and the island of Corsica in the Mediterranean.

Meanwhile, the Olympics haven’t necessarily been a boon to foreign tourism in the country. Many tourists who might have otherwise come to France are avoiding it this year in favour of other European capitals. In Paris, demand for stays at high-end hotels has collapsed, with bookings down 50% in July compared to last year, according to UMIH Prestige, which represents hotels charging at least €800 ($865) a night for rooms.

Earlier this year, high-end restaurants and concierges said the Olympics might even be an opportunity to score a hard-get-seat at the city’s fine dining.

In the Occitanie region in southwest France, the overall number of reservations this summer hasn’t changed much from last year, says Vincent Gare, president of the regional tourism committee there.

“But looking further at the numbers, we do see an increase in the clientele coming from the Paris region,” Gare told Le Figaro, noting that the increase in reservations has fallen directly on the dates of the Olympic games.

Michel Barré, a retiree living in Paris’s Le Marais neighbourhood, is one of those opting for the beach rather than the opening ceremony. In January, he booked a stay in Normandy for two weeks.

“Even though it’s a major European capital, Paris is still a small city—it’s a massive effort to host all of these events,” Barré says. “The Olympics are going to be a mess.”

More than anything, he just wants some calm after an event-filled summer in Paris, which just before the Olympics experienced the drama of a snap election called by Macron.

“It’s been a hectic summer here,” he says.

AFP via Getty Images

Parisians—Barré included—feel that the city, by over-catering to its tourists, is driving out many residents.

Parts of the Seine—usually one of the most popular summertime hangout spots —have been closed off for weeks as the city installs bleachers and Olympics signage. In certain neighbourhoods, residents will need to scan a QR code with police to access their own apartments. And from the Olympics to Sept. 8, Paris is nearly doubling the price of transit tickets from €2.15 to €4 per ride.

The city’s clear willingness to capitalise on its tourists has motivated some residents to do the same. In March, the number of active Airbnb listings in Paris reached an all-time high as hosts rushed to list their apartments. Listings grew 40% from the same time last year, according to the company.

With their regular clients taking off, Parisian restaurants and merchants are complaining that business is down.

“Are there any Parisians left in Paris?” Alaine Fontaine, president of the restaurant industry association, told the radio station Franceinfo on Sunday. “For the last three weeks, there haven’t been any here.”

Still, for all the talk of those leaving, there are plenty who have decided to stick around.

Jay Swanson, an American expat and YouTuber, can’t imagine leaving during the Olympics—he secured his tickets to see ping pong and volleyball last year. He’s also less concerned about the crowds and road closures than others, having just put together a series of videos explaining how to navigate Paris during the games.

“It’s been 100 years since the Games came to Paris; when else will we get a chance to host the world like this?” Swanson says. “So many Parisians are leaving and tourism is down, so not only will it be quiet but the only people left will be here for a party.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.