Stressed by Smart Tech? Consider These ‘Dumb’ Devices

As our appliances and gadgets become more connected, they become more prone to unexpected bugs and glitches.

ONCE, a broken bathroom scale just displayed the wrong weight. In 2022, it won’t even do that.

“My scale stopped connecting to Wi-Fi, which for some reason means it won’t even show the weight,” said Chris Hoffman, editor in chief of How-to Geek, an online magazine devoted to helping people understand their tech. In short, he’s an expert at troubleshooting broken gadgets. But when Mr. Hoffman’s scale went on the fritz, it just sat stubbornly broken on his coffee table, even after he’d read the entire manual, researched whether others had experienced the same problem, hounded customer support and coaxed the device through a complete factory reset. “I was left thinking ‘Where did I go wrong with my life?’” he said.

“Smart” spins on common home appliances have been available for many years. These clever refrigerators, televisions and air conditioners perform their base functions, but also use their ability to connect to the internet to unlock additional conveniences—letting owners, for instance, remote-control them from miles away. Generally, that level of interactivity was something you would opt into, by buying a robot vacuum, smart speakers or an Alexa-enabled microwave. But it wasn’t the default.

That’s changing. While some brands are aggressively bucking the trend and producing intentionally untethered devices, it’s getting harder to purchase appliances and gadgets that don’t need an internet connection merely to function properly. “I’ve gotten so many emails from readers who are looking for a ‘dumb’ TV,” said Mr. Hoffman. “Unfortunately, that doesn’t exist.”

While a TV that can’t access Netflix in the age of cord-cutting isn’t very useful, the trend has taken hold outside the living room too. Increasingly, said Jerry Beilinson, technology editor at Consumer Reports, “you can’t buy a high-end washing machine or dishwasher or dryer without it having Wi-Fi connectivity.”

When it comes to smart appliances beyond TVs, the benefits are less obvious. While it is convenient to zap your popcorn without pressing any of a microwave’s buttons, either via a phone app or through a voice assistant, when every device is, on some level, a computer, there are downsides. We’ve all heard stories about some household object that, a la Mr. Hoffman’s confoundingly sophisticated scale, stops working because the “smart” technology inside it breaks. Mr. Hoffman says he’s encountered washing machines that won’t let you clean your clothes until you’ve downloaded and installed a firmware update. “It is just annoying,” he said.

The problems aren’t always due to glitches or necessary security updates. Sometimes companies disable features intentionally. Mr. Beilinson said data collection offers a simple way for companies to make devices more profitable: “Adding Wi-Fi connectivity to appliances is extremely cheap and the data companies get out of it is extremely valuable.” Requiring that people connect to Wi-Fi in order to use features means more will connect. The brands are nudging, or arguably forcing, you to accept the intrusion.

For example, GE has engineered some of its ovens so that you can’t use the convection roast feature unless you connect them to Wi-Fi and download an app to your phone. This despite the fact that many residential ovens have had convection features since 1945, when the Wi-Fi in most homes was, shall we say, spotty. (A GE Appliances spokesperson said the company makes plenty of appliances that do not require Wi-Fi connectivity, but also wants to give customers the option of increased technological capability.)

The story is the same in the living room. Roku, for example, might be best known for its streaming sticks and smart televisions, but the company actually earns most of its money from the streaming platform it designed. According to its 2021 earnings report, the company actually lost $52 million from sales of hardware. The model works because of how effectively the company has been able to monetize its platform through licensing and advertising. Roku identified “targeting using first-party data” as its fastest-growing ad product last year, by which it means leveraging the information it gets from tracking your viewing habits to serve you new shows to watch or products you can buy directly from your TV. (Roku declined to comment for this article.)

Sometimes, it is still possible to opt out of this kind of tracking. Mr. Beilinson owns a garage door opener that could be controlled with an app, but he hasn’t connected the device to Wi-Fi. “I don’t feel like I need to tell a company every time I open the garage door.”

But more often than not, avoiding the downsides of smart tech requires awkward, costly workarounds. Mr. Hoffman said some people avoid connecting their TVs to Wi-Fi to ensure their viewing habits cannot be tracked. But then they must purchase an extra device to watch their top shows. “People who are really into privacy prefer the Apple TV box,” he said, pointing out that Apple considers its customer’s privacy a high priority. Others might rightfully bristle at the idea of spending an extra $180 to ensure a new TV doesn’t track their behaviour.

Deciding which devices you want to connect to the internet is a balancing act. But some signs suggest that people are seeking actively unconnected “dumb” devices. For example, in an earnings report last year, Fujifilm, the Japanese camera company, said it has made more money in each of the last five years from its line of Instax instant film cameras and accessories than it has from selling digital cameras and their lenses.

The analog trend is also manifesting in gaming. Wizards of The Coast, which makes the dice-rolling, pen-and-paper-based Dungeons & Dragons series and the card game Magic: The Gathering, saw a revenue increase of 24%, up to US$816 million, from 2019 to 2020. Even when Pandemic-induced lockdowns made in-person gaming impossible, many chose to invest in games that they could play in person, once restrictions were lifted. “There is a subset of people who are looking for ways to reduce the role of technology in their lives, to not always be so connected,” said Mr. Beilinson, “people looking for physical experiences.”

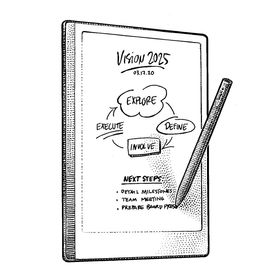

Startups are emerging specifically to cater to such people. One is reMarkable, which makes tablets for writing that might look, at first glance, like an iPad. The difference: no extra apps and a black-and-white e-ink screen. It is as close as you can get to a digital piece of paper, which is exactly the point. “When you’re writing and thinking your best thoughts, it is really important that you don’t get an email or a notification that takes you out of that,” said Henrik Gustav Faller, vice president of communication at reMarkable. “That stream of thought is something that we really try to focus on and really cherish.”

The 300-person reMarkable team, based in Norway, spent years developing the tablet before launch—reducing the latency on the screen and contemplating how much the pen should weigh. The end product has a few smart features—one gives users access to files on Dropbox and Google Drive—but not many. It appears the approach is working: As of 2020, reMarkable has sold over half a million devices. A company representative said sales increased in 2021, but they declined to release specific numbers.

The Light Phone II is a tiny brick with a similar black-and-white e-ink screen—and a similar philosophy. Designed by a 13 person team in New York City, it supports calls and texts, but no social media. Kaiwei Tang, co-founder and CEO, said that is because he believes our phones currently do way too much. That’s why there is no Light Phone app store; you can, however, download a few “tools” that let you do simple things like get directions or listen to podcasts. The phone, which launched in 2019, saw a 150% increase in sales from release to 2021 according to Mr. Tang. Investors include Twitter co-founder Biz Stone and Adobe chief product officer Scott Belsky.

These kinds of devices are made by and for people who are contemplating their relationship with technology and intentionally opting for simpler, less distracting devices. They offer a reminder that we should be able to choose how we interact with our technology, and how it interacts with us.

Everyone has a different threshold for what is and isn’t useful—and some smart devices might do enough to make the odd annoyance worth bearing. But since no company will make this calculation for you, Mr. Hoffman said it’s important to consider what you actually want: “Even if you love smart technology, not everything needs to be smart.”

The Best Dumb Tech

Eight pieces of gear that make the case for a future of less-connected devices

Light Phone II

It lets you make calls and send texts, but not much else. It’s designed to be used as little as possible, though you can add optional “Tools” like GPS navigation and podcasts.

The Mohu Leaf Plus Amplified TV Antenna

Free broadcast TV still exists, and it has been in HD for over a decade now. Cheap, powerful indoor antennas like this one allow you to rediscover the experience.

Mighty

Like the iPod Shuffle for the streaming age, this device lets you sync songs over from Spotify or Amazon Music to listen offline. It’s great for working out, when picking the perfect playlist can easily become an excuse to dawdle near a squat rack.

Kindle Paperwhite

Thanks to a crisp, responsive screen and light body, the Kindle is a superior e-reader. Cheaper Kindles like the Paperwhite include some bloat like ads and a web browser. Both are easy to ignore, especially since the browser is harder to use than “Ulysses” is to read.

reMarkable 2

As close as you can get to a digital pad of paper. This thin tablet comes with a realistic-feeling pen, which you can use to mark up documents and sync notes to your phone or computer.

Freewrite

This digital typewriter—nothing more than a mechanical keyboard with an e-ink screen—lets you draft without distraction. To edit, you can send text to your computer.

The Fujifilm Instax 11

An instant camera like the Polaroids of old, it prints an actual physical photo that you can share with a friend by handing it to them. What a concept.

BN-LINK Mini 24-hour Mechanical Outlet Timer

Decades after the servers for smart plugs currently on the market shut down, this little mechanical timer will keep on ticking—and you can get two for 12 bucks.

Even a sceptic can appreciate some smart tech. Three winners…

Adaptive Central Air

The Google Nest Learning Thermostat can, by some estimates, reduce your heating and cooling bills by 10 to 15% by not using energy when it’s not needed. If you’re going to introduce smart tech to your house, it might as well be saving you money (and reducing your carbon footprint).

Secure Streaming

Apple TV is one of the few visual entertainment platforms that doesn’t track and monetize your viewing habits, according to privacy experts. Plus, these boxes will continue getting security updates much longer than your run-of-the-mill smart television.

Flexible Fixtures

The Wyze Bulb Color is an affordable LED smart bulb that can make any lamp or sconce colourful. Customize the colour or intensity with your phone at any moment or schedule the bulbs to turn off and on at specific times then forget about them completely.

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

As Paris makes its final preparations for the Olympic games, its residents are busy with their own—packing their suitcases, confirming their reservations, and getting out of town.

Worried about the hordes of crowds and overall chaos the Olympics could bring, Parisians are fleeing the city in droves and inundating resort cities around the country. Hotels and holiday rentals in some of France’s most popular vacation destinations—from the French Riviera in the south to the beaches of Normandy in the north—say they are expecting massive crowds this year in advance of the Olympics. The games will run from July 26-Aug. 1.

“It’s already a major holiday season for us, and beyond that, we have the Olympics,” says Stéphane Personeni, general manager of the Lily of the Valley hotel in Saint Tropez. “People began booking early this year.”

Personeni’s hotel typically has no issues filling its rooms each summer—by May of each year, the luxury hotel typically finds itself completely booked out for the months of July and August. But this year, the 53-room hotel began filling up for summer reservations in February.

“We told our regular guests that everything—hotels, apartments, villas—are going to be hard to find this summer,” Personeni says. His neighbours around Saint Tropez say they’re similarly booked up.

As of March, the online marketplace Gens de Confiance (“Trusted People”), saw a 50% increase in reservations from Parisians seeking vacation rentals outside the capital during the Olympics.

Already, August is a popular vacation time for the French. With a minimum of five weeks of vacation mandated by law, many decide to take the entire month off, renting out villas in beachside destinations for longer periods.

But beyond the typical August travel, the Olympics are having a real impact, says Bertille Marchal, a spokesperson for Gens de Confiance.

“We’ve seen nearly three times more reservations for the dates of the Olympics than the following two weeks,” Marchal says. “The increase is definitely linked to the Olympic Games.”

Getty Images

According to the site, the most sought-out vacation destinations are Morbihan and Loire-Atlantique, a seaside region in the northwest; le Var, a coastal area within the southeast of France along the Côte d’Azur; and the island of Corsica in the Mediterranean.

Meanwhile, the Olympics haven’t necessarily been a boon to foreign tourism in the country. Many tourists who might have otherwise come to France are avoiding it this year in favour of other European capitals. In Paris, demand for stays at high-end hotels has collapsed, with bookings down 50% in July compared to last year, according to UMIH Prestige, which represents hotels charging at least €800 ($865) a night for rooms.

Earlier this year, high-end restaurants and concierges said the Olympics might even be an opportunity to score a hard-get-seat at the city’s fine dining.

In the Occitanie region in southwest France, the overall number of reservations this summer hasn’t changed much from last year, says Vincent Gare, president of the regional tourism committee there.

“But looking further at the numbers, we do see an increase in the clientele coming from the Paris region,” Gare told Le Figaro, noting that the increase in reservations has fallen directly on the dates of the Olympic games.

Michel Barré, a retiree living in Paris’s Le Marais neighbourhood, is one of those opting for the beach rather than the opening ceremony. In January, he booked a stay in Normandy for two weeks.

“Even though it’s a major European capital, Paris is still a small city—it’s a massive effort to host all of these events,” Barré says. “The Olympics are going to be a mess.”

More than anything, he just wants some calm after an event-filled summer in Paris, which just before the Olympics experienced the drama of a snap election called by Macron.

“It’s been a hectic summer here,” he says.

AFP via Getty Images

Parisians—Barré included—feel that the city, by over-catering to its tourists, is driving out many residents.

Parts of the Seine—usually one of the most popular summertime hangout spots —have been closed off for weeks as the city installs bleachers and Olympics signage. In certain neighbourhoods, residents will need to scan a QR code with police to access their own apartments. And from the Olympics to Sept. 8, Paris is nearly doubling the price of transit tickets from €2.15 to €4 per ride.

The city’s clear willingness to capitalise on its tourists has motivated some residents to do the same. In March, the number of active Airbnb listings in Paris reached an all-time high as hosts rushed to list their apartments. Listings grew 40% from the same time last year, according to the company.

With their regular clients taking off, Parisian restaurants and merchants are complaining that business is down.

“Are there any Parisians left in Paris?” Alaine Fontaine, president of the restaurant industry association, told the radio station Franceinfo on Sunday. “For the last three weeks, there haven’t been any here.”

Still, for all the talk of those leaving, there are plenty who have decided to stick around.

Jay Swanson, an American expat and YouTuber, can’t imagine leaving during the Olympics—he secured his tickets to see ping pong and volleyball last year. He’s also less concerned about the crowds and road closures than others, having just put together a series of videos explaining how to navigate Paris during the games.

“It’s been 100 years since the Games came to Paris; when else will we get a chance to host the world like this?” Swanson says. “So many Parisians are leaving and tourism is down, so not only will it be quiet but the only people left will be here for a party.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.