Why Inflation Erupted: Two Top Economists Have the Answer

Former Fed chair, IMF chief economist say it wasn’t pandemic or stimulus; it was the pandemic, then the stimulus

For two years debate has raged over what caused the highest inflation since the 1980s: government stimulus or pandemic-related disruptions.

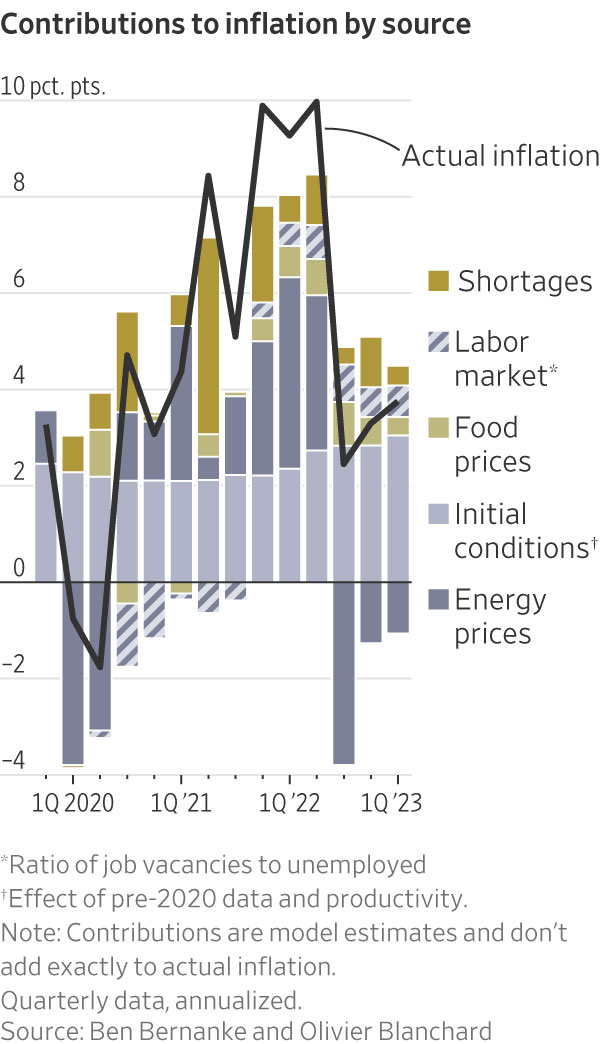

Now two of the country’s top economists have an answer: It’s both. Pandemic-related supply shocks explain why inflation shot up in 2021. An economy overheated by fiscal stimulus and low interest rates explain why it has stayed high ever since. The conclusion: For inflation to fade, the economy has to cool off, which means a weaker labour market.

The study, released Tuesday, is by Ben Bernanke, former chair of the Federal Reserve, and Olivier Blanchard, former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund. Bernanke is now at the Brookings Institution and Blanchard is at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. The two are among the world’s most cited academic economists.

When Congress passed President Biden’s $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan in early 2021, which included checks to households, enhanced jobless benefits and aid to state and local governments, inflation was around 2% and unemployment, though coming down, still above 6%.

At the time many forecasters thought the stimulus could push demand above the economy’s potential to supply goods and services and unemployment below its long-run natural rate of around 4%. Yet few thought this would meaningfully raise inflation. In previous decades unemployment had remained similarly low without raising price pressures.

A few disagreed, notably former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers and Blanchard. Both warned the stimulus was so large it would push the economy dangerously into overheating territory.

Not the inflation critics expected

Inflation did shoot up, hitting 7% that December, 5.5% excluding food and energy. “The critics’ forecasts of higher inflation would prove to be correct—indeed, even too optimistic—but, in substantial part, the sources of the inflation would prove to be different from those they warned about,” Blanchard, one of those critics, and Bernanke write in their study.

To tease out the sources of inflation, Bernanke and Blanchard build a relatively conventional model in which inflation is a function of, among other things, the gap between the supply and demand for labor, the public’s expectations of inflation, and commodity prices. They include a variable for supply-chain disruptions derived from Google searches for “shortage.”

Usually economists judge labor market tightness from how far unemployment is above or below its natural rate. But this time the labor market heated up before unemployment got that low. So instead, Bernanke and Blanchard use the ratio of job vacancies to unemployed workers. Finally, their model lets all these factors interact, with varying lags.

If stimulus had overheated the economy, it should have shown up in the labor market, i.e., an unusually high ratio of vacancies to unemployed. In fact, labor market conditions put downward pressure on inflation through the third quarter of 2021, the authors concluded. Instead, the inflation that year was driven almost entirely by shortages and energy prices. (To be sure, many shortages reflected restricted supply interacting with demand boosted by stimulus.)

Demand shifted abruptly from services to goods in the early months of the pandemic. The overall effect should have been a wash as prices rose for goods and fell for services. It wasn’t, because goods producers faced supply constraints, which caused costs and prices to spike, while costs to service producers didn’t decline much. “These sectoral mismatches between demand and supply proved more intractable and longer-lasting than many had expected,” the authors note.

The legacy of stimulus

These pandemic disruptions did eventually subside. Why didn’t inflation then fall? The reason, the authors conclude, is that by this point demand was so strong, reflecting the legacy of low interest rates and fiscal largess, the labor market was significantly overheated with the ratio of vacancies to unemployed up dramatically. Moreover, the initial surge of inflation had an echo: It lifted workers’ expectations of short-term inflation, which then partly found its way into their wages.

If anything, the study might understate the effect of pandemic disruptions. The labor market didn’t just overheat because of excess demand, but reduced supply, as well. The rising ratio of vacancies to unemployed, which the model equates with a tighter labor market, reflects employers struggling to fill vacancies. The authors note much of that struggle was because of the pandemic: Firms that had laid off employees had to find new ones, while some workers left the labor force because of family obligations, illness or work-life balance priorities.

This decline in supply-side potential hasn’t gotten much attention in the inflation debate, but its role could be significant. John Williams, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, last week estimated that potential was 4.2% lower at the end of 2022 than its pre pandemic trend.

That stimulus wasn’t the inflation culprit it is often made out to be doesn’t entirely absolve the Fed and Biden. Arguably, they should have anticipated supply disruptions would amplify the risks of stoking demand. In 2020 the Fed introduced a new framework and guidance under which interest rates would stay near zero until maximum employment was restored, even if inflation topped its 2% target. That “contributed to delayed action and the inflation overshoot,” former Fed Vice Chair Donald Kohn and Brown University economist Gauti B. Eggertsson say in another paper to be presented Tuesday.

Bernanke and Blanchard conclude that because inflation today reflects a too-hot labor market, the solution is to cool it off. To bring inflation back to the Fed’s target, they estimate unemployment would have to rise above 4.3% from its current 3.4% assuming vacancies remain difficult to fill. But, they say, inflation could drop without a significant increase in unemployment if the ease of hiring returns to pre pandemic norms. The good news: There are tentative signs that is happening.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

As Paris makes its final preparations for the Olympic games, its residents are busy with their own—packing their suitcases, confirming their reservations, and getting out of town.

Worried about the hordes of crowds and overall chaos the Olympics could bring, Parisians are fleeing the city in droves and inundating resort cities around the country. Hotels and holiday rentals in some of France’s most popular vacation destinations—from the French Riviera in the south to the beaches of Normandy in the north—say they are expecting massive crowds this year in advance of the Olympics. The games will run from July 26-Aug. 1.

“It’s already a major holiday season for us, and beyond that, we have the Olympics,” says Stéphane Personeni, general manager of the Lily of the Valley hotel in Saint Tropez. “People began booking early this year.”

Personeni’s hotel typically has no issues filling its rooms each summer—by May of each year, the luxury hotel typically finds itself completely booked out for the months of July and August. But this year, the 53-room hotel began filling up for summer reservations in February.

“We told our regular guests that everything—hotels, apartments, villas—are going to be hard to find this summer,” Personeni says. His neighbours around Saint Tropez say they’re similarly booked up.

As of March, the online marketplace Gens de Confiance (“Trusted People”), saw a 50% increase in reservations from Parisians seeking vacation rentals outside the capital during the Olympics.

Already, August is a popular vacation time for the French. With a minimum of five weeks of vacation mandated by law, many decide to take the entire month off, renting out villas in beachside destinations for longer periods.

But beyond the typical August travel, the Olympics are having a real impact, says Bertille Marchal, a spokesperson for Gens de Confiance.

“We’ve seen nearly three times more reservations for the dates of the Olympics than the following two weeks,” Marchal says. “The increase is definitely linked to the Olympic Games.”

Getty Images

According to the site, the most sought-out vacation destinations are Morbihan and Loire-Atlantique, a seaside region in the northwest; le Var, a coastal area within the southeast of France along the Côte d’Azur; and the island of Corsica in the Mediterranean.

Meanwhile, the Olympics haven’t necessarily been a boon to foreign tourism in the country. Many tourists who might have otherwise come to France are avoiding it this year in favour of other European capitals. In Paris, demand for stays at high-end hotels has collapsed, with bookings down 50% in July compared to last year, according to UMIH Prestige, which represents hotels charging at least €800 ($865) a night for rooms.

Earlier this year, high-end restaurants and concierges said the Olympics might even be an opportunity to score a hard-get-seat at the city’s fine dining.

In the Occitanie region in southwest France, the overall number of reservations this summer hasn’t changed much from last year, says Vincent Gare, president of the regional tourism committee there.

“But looking further at the numbers, we do see an increase in the clientele coming from the Paris region,” Gare told Le Figaro, noting that the increase in reservations has fallen directly on the dates of the Olympic games.

Michel Barré, a retiree living in Paris’s Le Marais neighbourhood, is one of those opting for the beach rather than the opening ceremony. In January, he booked a stay in Normandy for two weeks.

“Even though it’s a major European capital, Paris is still a small city—it’s a massive effort to host all of these events,” Barré says. “The Olympics are going to be a mess.”

More than anything, he just wants some calm after an event-filled summer in Paris, which just before the Olympics experienced the drama of a snap election called by Macron.

“It’s been a hectic summer here,” he says.

AFP via Getty Images

Parisians—Barré included—feel that the city, by over-catering to its tourists, is driving out many residents.

Parts of the Seine—usually one of the most popular summertime hangout spots —have been closed off for weeks as the city installs bleachers and Olympics signage. In certain neighbourhoods, residents will need to scan a QR code with police to access their own apartments. And from the Olympics to Sept. 8, Paris is nearly doubling the price of transit tickets from €2.15 to €4 per ride.

The city’s clear willingness to capitalise on its tourists has motivated some residents to do the same. In March, the number of active Airbnb listings in Paris reached an all-time high as hosts rushed to list their apartments. Listings grew 40% from the same time last year, according to the company.

With their regular clients taking off, Parisian restaurants and merchants are complaining that business is down.

“Are there any Parisians left in Paris?” Alaine Fontaine, president of the restaurant industry association, told the radio station Franceinfo on Sunday. “For the last three weeks, there haven’t been any here.”

Still, for all the talk of those leaving, there are plenty who have decided to stick around.

Jay Swanson, an American expat and YouTuber, can’t imagine leaving during the Olympics—he secured his tickets to see ping pong and volleyball last year. He’s also less concerned about the crowds and road closures than others, having just put together a series of videos explaining how to navigate Paris during the games.

“It’s been 100 years since the Games came to Paris; when else will we get a chance to host the world like this?” Swanson says. “So many Parisians are leaving and tourism is down, so not only will it be quiet but the only people left will be here for a party.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.