Here Comes the 60-Year Career

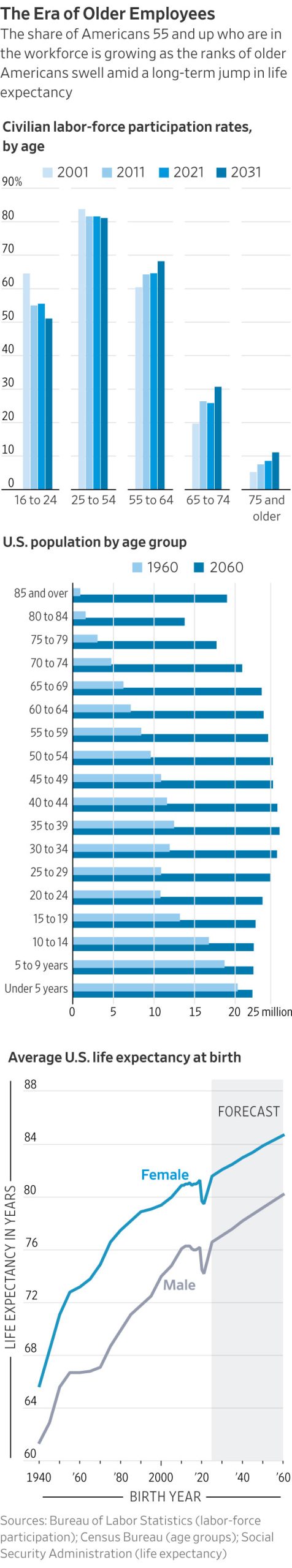

As people live longer, healthier lives, the traditional 40-year career will become a thing of the past. But that’s going to require a new mind-set—and a lot more planning.

Get ready for longer careers. Probably much longer.

Charlotte Japp is setting the groundwork for it. Since graduating from college 10 years ago, Ms. Japp has worked in marketing at three companies in different industries and simultaneously launched Cirkel, a startup that connects younger and older employees for two-way career support.

Currently head of platform at ff Venture Capital in New York, Ms. Japp, 32, doesn’t see her career as linear, and doesn’t picture her progression as moving up a single, well-defined ladder. Instead, she envisions her career as long and varied—a marathon that will involve changing directions, with stops and restarts along the way.

“I know I’m going to have a career over a very long stretch and it won’t be just one thing,” Ms. Japp says. “Plus there’ll be more fluidity between periods of work, school and family.”

Millennials like Ms. Japp, as well as the generations behind them, are starting to think about their careers in a totally different way from their elders. They have no choice: Because they are likely to live healthily into their 90s or longer, they must learn to navigate 60-year careers instead of the traditional 40-year span.

But such a change will require a new mind-set when it comes to planning a career. Instead of advancing vertically up a single path, for instance, people will need to move sideways—and even down at times—as they traverse different jobs and multiple careers. They will have to make sure they have adequate income to sustain themselves over lengthy lives. They will need to figure out where they derive the most job satisfaction so they don’t burn out after decades of working. They will have to keep acquiring new skills to avoid becoming obsolete. And, if they can afford to, they may want to take occasional career breaks to balance their personal and professional lives.

“Over the course of 60-year careers, we’ll need to work and pace our careers differently,” says Laura Carstensen, founding director of the Stanford Center on Longevity.

Currently, Dr. Carstensen says, men and women at midlife “tend to burn the career-and-family candle at both ends, with lives impossibly packed from morning to night,” while older people who are plateaued or pushed out before wanting to stop working feel underused. She imagines a model where people might work about the same amount of time overall as they do now, but spread that work over more years—thereby reducing the risk of burnout and giving themselves time for personal pursuits and skill enhancement.

All of this could pose challenges for companies, which haven’t structured ways for employees to stay productive and creative over lengthy careers. Few have established flexible routes in and out of the workplace, or “glide paths” toward retirement that enable older workers to work longer but at reduced hours. Less than 10% of Fortune 500 companies have re-entry programs for employees who have taken career breaks for family caregiving or other reasons, according to research by Boston-based iRelaunch, which encourages employers to establish such programs, and helps people return to work after breaks of one to 20 years.

However, if they want to attract the workers they need, employers will have no choice but to adapt. After all, their leaders will likely be in the same position.

Here are seven things for employees to think about as they plan for—and navigate—this new terrain.

1. Expect a career that resembles a jungle gym rather than a ladder

Already, a lot fewer workers expect to stay at a single company throughout their career. That trend will only accelerate as careers get longer. After all, few people will want to stay at the same job for 60 years, even if they could (a big if). It is a recipe for job and life dissatisfaction and stagnant income. And few companies have shown the kind of loyalty that would encourage such careers.

Instead, employees should imagine a career that involves making leaps sideways and across rungs rather than a straight climb upward.

Ms. Japp says she learned to expect this by observing her parents, who both lost corporate jobs in midlife and then successfully pivoted to self-employment. Her father, after a career in advertising, established a stamp- and coin-selling business on eBay, and her mother became an independent adviser to art collectors after working as an executive at a large art gallery.

“The idea of portfolio careers, and change being a positive, was implanted in me early,” Ms. Japp says. Over any career, but especially a lengthy one, you need to cope with two ever-changing variables, says Ms. Japp. “First is the business world, where new companies and many new jobs will be constantly emerging. And personally we change over time—and so do our interests, needs and curiosity.”

2. Lifelong learning, including breaks to return to school, will be essential

It is hard enough now to stay up-to-date with technology and other job requirements, and to train for new opportunities. Add 20 years to careers, and it becomes even more daunting. In addition, many employees will want to start second or third careers over the course of their longer working lives, which will require returning to school for training and maybe even new degrees.

Giulia Pines, who’s 38, worked as a freelance writer—first in Germany where she lived for a decade and then in New York. Two years ago, in the wake of the Black Lives Matter and other social-justice protests, she thought about becoming a lawyer and “trying to change policies and help people, but at first I thought I was too old to make that switch,” she says. Then, she realised she likely has decades ahead of her to devote to law.

Ms. Pines is now a first-year student at Brooklyn Law School, has met several other classmates in their 30s and isn’t concerned about starting a law career at 40. “If I’m going to be 40 anyway, I might as well do what I want,” she says. Plus, she adds, she was raised in a family that “never considered retirement, with both my grandfather and father, who were doctors, working until they were unable to do that physically and mentally. I think of what I’m doing now as a next step, without an age attached to it.”

3. Seek flexibility to have a better work/life balance

As people live longer, and careers lengthen, their priorities change. They’ll also face conflicting demands. For instance, for growing numbers of young and middle-aged adults, caregiving responsibilities for older parents overlap with caring for young children. Among the 48 million Americans who currently provide unpaid care to elders or disabled relatives, more than 40% are 18 to 49 years old, according to a 2020 study by AARP and the National Alliance for Caregiving.

“Everyone is going to be a caregiver at some point, and it should be an acknowledged part of a 60-year career,” says Susan Golden, who advises companies and venture firms about innovation and entrepreneurial opportunities created by longevity.

Ms. Golden is a living example of her argument. She was a partner at a venture-capital company in her 30s, and took only three weeks off after having her first daughter. But she took a break after having a second daughter when she also began caring for her mother. Now she’s encouraging her daughters and other millennials to consider caregiving breaks themselves “so you don’t miss out on the joy of raising children. You don’t have to work straight through 60 years,” she says.

After her own break of about 15 years, Ms. Golden attended Stanford University’s Distinguished Careers Institute when she was 61, or what she calls her “renaissance stage.” She took courses on such topics as entrepreneurship and board governance at Stanford Graduate School of Business, healthy aging at the medical school and on design thinking. And she was among others in their 50s and older who were considering transitions. “Having the support of that community was so helpful,” says Ms. Golden, who also co-teaches a course about longevity’s business opportunities at Stanford’s business school and is the author of “Stage (Not Age).”

4. Learn strategies for restarting a career after a break

In March 2022, LinkedIn introduced a new category—Career Breaks—for users who are building profiles to describe the highlights of their time away from traditional jobs, including family responsibilities, volunteerism and travel. The new label should help normalize the idea that careers aren’t always linear.

Carol Fishman Cohen, chief executive and co-founder of iRelaunch, advises employees to keep detailed notes throughout their careers, not just about achievements but about specific experiences they have had with bosses, employees and colleagues at different jobs. It’s hard enough to remember accomplishments five or 10 years later, but 40 or 50 years? “Those of us who don’t think to keep these records have to re-create the past from memory, which may not be nearly as vivid or compelling as when they occurred,” Ms. Cohen says.

Those who take breaks should keep up-to-date on licenses and professional membership, take online courses to improve and learn new skills and possibly do part-time volunteering or contract work. “Use time during a break to reflect on your strengths and whether you want to return to the path you were on or take a new direction,” says Ms. Cohen, and let prospective employers know that you’ve thought carefully during a break about your commitment to a particular field.

5. Build an intergenerational network

Over the course of a six-decade career, workers need to nurture relationships not just with superiors but with colleagues who are junior to them.

Colleagues who are younger may be more skilled with new technologies, and be able to help older colleagues learn and adapt to them. And because there aren’t clear career paths, it is more likely that positions will shift. A colleague who’s younger in age may advance beyond their former bosses and be in a position to hire them or connect them to other jobs. This happened to Ms. Cohen when she wanted to re-enter the workplace after an 11-year caregiving break: She got a job at Bain Capital, where a former junior colleague she had previously worked with at a different finance company had a key position. He remembered her and helped connect her to others at Bain who hired her, she says.

6. Explore new paths even when you’re enjoying your current career

It’s typical for people to keep their heads down and focus on the job and employer they have, especially if they are satisfied. But in an era of long, multiple careers, it’s important to think about alternative paths before you have to or feel pressured to make a change. The odds are much greater that you’ll need to take that path one day.

To that end, experts advise people to attend professional meetings or conferences in areas they want to learn about, and to spend time thinking about what they might want to do next, just in case. Maybe somebody has worked in operations or IT, but imagines moving into human resources or marketing. It doesn’t hurt to talk with those people in those fields about what might be required. A safety net is a lot more important when you’re staring at, say, 30 more years of working than if you’re looking at 10 more years.

7. Don’t try to plan it all out

It is impossible to map out what will happen over a 60-year career. Too many things—in our personal lives, in the economy, in the workplace—will change. Nobody has a crystal ball that can look that far into the future.

What’s important, rather, is finding jobs and work environments that are both enjoyable and challenging. In the past, when careers typically involved a vertical climb, it made sense for employees to set goals they wanted to reach by a specific time or age. But trying to do this can be counterproductive today. The ability to be agile rather than rigidly focused on a handful of goals will be essential when traversing a career that lasts more than half a century.

“It is all about following my gut, knowing what I’m good at and doing what I enjoy on a day-to day basis,” says Ms. Japp. “The lesson I’ve been learning is to be adaptable. You have to meet the moment.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

As Paris makes its final preparations for the Olympic games, its residents are busy with their own—packing their suitcases, confirming their reservations, and getting out of town.

Worried about the hordes of crowds and overall chaos the Olympics could bring, Parisians are fleeing the city in droves and inundating resort cities around the country. Hotels and holiday rentals in some of France’s most popular vacation destinations—from the French Riviera in the south to the beaches of Normandy in the north—say they are expecting massive crowds this year in advance of the Olympics. The games will run from July 26-Aug. 1.

“It’s already a major holiday season for us, and beyond that, we have the Olympics,” says Stéphane Personeni, general manager of the Lily of the Valley hotel in Saint Tropez. “People began booking early this year.”

Personeni’s hotel typically has no issues filling its rooms each summer—by May of each year, the luxury hotel typically finds itself completely booked out for the months of July and August. But this year, the 53-room hotel began filling up for summer reservations in February.

“We told our regular guests that everything—hotels, apartments, villas—are going to be hard to find this summer,” Personeni says. His neighbours around Saint Tropez say they’re similarly booked up.

As of March, the online marketplace Gens de Confiance (“Trusted People”), saw a 50% increase in reservations from Parisians seeking vacation rentals outside the capital during the Olympics.

Already, August is a popular vacation time for the French. With a minimum of five weeks of vacation mandated by law, many decide to take the entire month off, renting out villas in beachside destinations for longer periods.

But beyond the typical August travel, the Olympics are having a real impact, says Bertille Marchal, a spokesperson for Gens de Confiance.

“We’ve seen nearly three times more reservations for the dates of the Olympics than the following two weeks,” Marchal says. “The increase is definitely linked to the Olympic Games.”

Getty Images

According to the site, the most sought-out vacation destinations are Morbihan and Loire-Atlantique, a seaside region in the northwest; le Var, a coastal area within the southeast of France along the Côte d’Azur; and the island of Corsica in the Mediterranean.

Meanwhile, the Olympics haven’t necessarily been a boon to foreign tourism in the country. Many tourists who might have otherwise come to France are avoiding it this year in favour of other European capitals. In Paris, demand for stays at high-end hotels has collapsed, with bookings down 50% in July compared to last year, according to UMIH Prestige, which represents hotels charging at least €800 ($865) a night for rooms.

Earlier this year, high-end restaurants and concierges said the Olympics might even be an opportunity to score a hard-get-seat at the city’s fine dining.

In the Occitanie region in southwest France, the overall number of reservations this summer hasn’t changed much from last year, says Vincent Gare, president of the regional tourism committee there.

“But looking further at the numbers, we do see an increase in the clientele coming from the Paris region,” Gare told Le Figaro, noting that the increase in reservations has fallen directly on the dates of the Olympic games.

Michel Barré, a retiree living in Paris’s Le Marais neighbourhood, is one of those opting for the beach rather than the opening ceremony. In January, he booked a stay in Normandy for two weeks.

“Even though it’s a major European capital, Paris is still a small city—it’s a massive effort to host all of these events,” Barré says. “The Olympics are going to be a mess.”

More than anything, he just wants some calm after an event-filled summer in Paris, which just before the Olympics experienced the drama of a snap election called by Macron.

“It’s been a hectic summer here,” he says.

AFP via Getty Images

Parisians—Barré included—feel that the city, by over-catering to its tourists, is driving out many residents.

Parts of the Seine—usually one of the most popular summertime hangout spots —have been closed off for weeks as the city installs bleachers and Olympics signage. In certain neighbourhoods, residents will need to scan a QR code with police to access their own apartments. And from the Olympics to Sept. 8, Paris is nearly doubling the price of transit tickets from €2.15 to €4 per ride.

The city’s clear willingness to capitalise on its tourists has motivated some residents to do the same. In March, the number of active Airbnb listings in Paris reached an all-time high as hosts rushed to list their apartments. Listings grew 40% from the same time last year, according to the company.

With their regular clients taking off, Parisian restaurants and merchants are complaining that business is down.

“Are there any Parisians left in Paris?” Alaine Fontaine, president of the restaurant industry association, told the radio station Franceinfo on Sunday. “For the last three weeks, there haven’t been any here.”

Still, for all the talk of those leaving, there are plenty who have decided to stick around.

Jay Swanson, an American expat and YouTuber, can’t imagine leaving during the Olympics—he secured his tickets to see ping pong and volleyball last year. He’s also less concerned about the crowds and road closures than others, having just put together a series of videos explaining how to navigate Paris during the games.

“It’s been 100 years since the Games came to Paris; when else will we get a chance to host the world like this?” Swanson says. “So many Parisians are leaving and tourism is down, so not only will it be quiet but the only people left will be here for a party.”

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.