Is China’s Economic Predicament as Bad as Japan’s? It Could Be Worse

From demographics to decoupling, China faces challenges Japan didn’t after its 1980s bubble

HONG KONG—Starting in the 1990s Japan became synonymous with economic stagnation, as a boom gave way to lethargic growth, declining population and deflation.

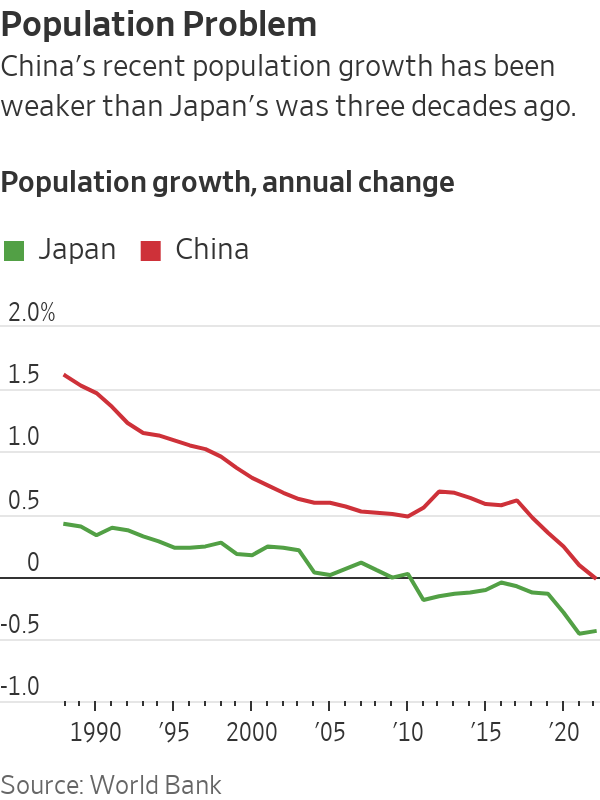

Many economists say China today looks similar. The reality: In many ways its problems are more intractable than Japan’s. China’s public debt levels are higher by some measures than Japan’s were and its demographics are worse. The geopolitical tensions that China is dealing with go beyond the trade frictions Japan once faced with the U.S.

Another headwind: China’s government, which has been cracking down on the private sector in recent years, seems ideologically less inclined than Tokyo was then to support growth.

None of this means China is sure to repeat the years of economic stagnation that Japan is only now showing signs of exiting. It has some advantages that Japan didn’t. Its economic growth in coming years is likely to be well above Japan’s in the 1990s.

Even so, economists say the parallels are a warning for Communist Party leaders in Beijing: If they don’t act more forcefully, the country could get stuck in a protracted period of economic sluggishness similar to Japan’s. Despite piecemeal steps in recent weeks, including modest interest-rate cuts, Beijing has held back on major stimulus to revive growth.

“China’s policy responses so far could put it on track for ‘Japanification,’” said Johanna Chua, chief Asia economist at Citigroup. She believes China’s overall growth prospects could be slowing more sharply than Japan’s.

China today and Japan 30 years ago share many similarities, including high debt levels, an aging population and signs of deflation.

During a long postwar economic expansion, Japan became an export powerhouse that American politicians and corporate executives worried would be unstoppable. Then in the early 1990s, real estate and stock market bubbles burst and the economy hit the skids.

Policy makers cut interest rates to virtually zero, but growth failed to rebound as consumers and companies focused on repaying debt to repair their balance sheets instead of borrowing to finance new spending and investment.

Richard Koo, an economist at the research arm of Japanese investment bank Nomura Securities, famously coined the term “balance sheet recession” to describe the phenomenon.

China, too, has seen a property bubble pop after years of extraordinary economic growth. Chinese consumers are now paying off mortgages early, despite government efforts to get them to borrow and spend more.

Private firms are also reluctant to invest despite lower interest rates, stirring anxiety among economists that monetary easing might be losing its potency in China.

By some measures, China’s asset bubbles aren’t as big. Morgan Stanley estimates that China’s ratio of property value to gross domestic product peaked at 260% in 2020, up from 170% of GDP in 2014; home prices have only fallen slightly since the peak, according to official data. China’s equity markets hit a recent peak of 80% of GDP in 2021 and now sit at 67% of GDP.

In Japan, land values as a percentage of GDP reached 560% of GDP in 1990 before falling back to 394% by 1994, Morgan Stanley estimates. The Tokyo Stock Exchange’s market capitalisation rose to 142% of GDP in 1989 from 34% in 1982.

Also in China’s favour, its urbanisation rate is lower, standing at 65% in 2022, versus Japan’s, which was at 77% in 1988. That could give China more potential to raise productivity and growth as people move to cities and take on nonagricultural jobs.

China’s tighter control over its capital markets means the risk of a sharp appreciation of its currency, which would harm exports, is low. Japan had to deal with a sharp increase in its currency several times in recent decades, which at times added to its economic struggles.

“We believe worries on China being trapped in a balance sheet recession are overdone,” economists from Bank of America recently wrote.

Yet in other ways, China’s problems will be harder to tackle than Japan’s.

Its population is ageing faster; it began to decline in 2022. In Japan, that didn’t happen until 2008, nearly two decades after its bubble burst.

Worse, China appears to be entering a period of weaker long-term growth rates before reaching rich-world status, i.e. it is getting old before it gets rich: China’s per capita income was $12,850 in 2022, much lower than Japan in 1991 at $29,080, World Bank data shows.

Then there is the problem of debt. Once off-balance-sheet borrowing by local governments is factored in, total public debt in China reached 95% of GDP in 2022, compared with 62% of GDP in Japan in 1991, according to J.P. Morgan. That limits authorities’ ability to pursue fiscal stimulus.

External pressures also appear to be tougher for China. Japan faced a lot of heat from its trading partners, but as a military ally of the U.S., it never risked a “new Cold War”—as some analysts now describe the U.S.-China relationship. Efforts by the U.S. and its allies to block China’s access to advanced technologies and reduce reliance on Chinese supply chains have sparked a plunge in foreign direct investment into China this year, which could significantly slow growth in the long run.

Many analysts worry Beijing is underestimating the risk of long-term stagnation—and doing too little to avoid it. Moderate cuts to key interest rates, lowering down payment ratios for apartments and recent vocal support for the private sector have done little to revive sentiment so far. Economists including Xiaoqin Pi from Bank of America argue that more coordinated easing in fiscal, monetary and property policies will be needed to put China’s growth back on track.

But President Xi Jinping is ideologically opposed to increasing government support for households and consumers, which he derides as “welfarism.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.

Excluding the Covid-19 pandemic period, annual growth was the lowest since 1992

Australia’s commodity-rich economy recorded its weakest growth momentum since the early 1990s in the second quarter, as consumers and businesses continued to feel the impact of high interest rates, with little expectation of a reprieve from the Reserve Bank of Australia in the near term.

The economy grew 0.2% in the second quarter from the first, with annual growth running at 1.0%, the Australian Bureau of Statistics said Wednesday. The results were in line with market expectations.

It was the 11th consecutive quarter of growth, although the economy slowed sharply over the year to June 30, the ABS said.

Excluding the Covid-19 pandemic period, annual growth was the lowest since 1992, the year that included a gradual recovery from a recession in 1991.

The economy remained in a deep per capita recession, with gross domestic product per capita falling 0.4% from the previous quarter, a sixth consecutive quarterly fall, the ABS said.

A big area of weakness in the economy was household spending, which fell 0.2% from the first quarter, detracting 0.1 percentage point from GDP growth.

On a yearly basis, consumption growth came in at just 0.5% in the second quarter, well below the 1.1% figure the RBA had expected, and was broad-based.

The soft growth report comes as the RBA continues to warn that inflation remains stubbornly high, ruling out near-term interest-rate cuts.

RBA Gov. Michele Bullock said last month that near-term rate cuts aren’t being considered.

Money markets have priced in a cut at the end of this year, while most economists expect that the RBA will stand pat until early 2025.

Treasurer Jim Chalmers has warned this week that high interest rates are “smashing the economy.”

Still, with income tax cuts delivered at the start of July, there are some expectations that consumers will be in a better position to spend in the third quarter, reviving the economy to some degree.

“Output has now grown at 0.2% for three consecutive quarters now. That leaves little doubt that the economy is growing well below potential,” said Abhijit Surya, economist at Capital Economics.

“But if activity does continue to disappoint, the RBA could well cut interest rates sooner,” Surya added.

Government spending rose 1.4% over the quarter, due in part to strength in social-benefits programs for health services, the ABS said.

This stylish family home combines a classic palette and finishes with a flexible floorplan

Just 55 minutes from Sydney, make this your creative getaway located in the majestic Hawkesbury region.