From a Gangster’s ‘Rat Pit’ to Sunny Condos: Duplex Atop the Third-Oldest Building in Manhattan Lists for $US1.825 Million

The 250-year-old structure in the South Street Seaport District had a colorful past before a developer converted it to apartments in the 1990s

An apartment atop the third oldest building still standing in Manhattan has hit the market for $1.825 million.

The two-bedroom duplex occupies the top two floors of the Captain Joseph Rose house in the South Street Seaport District, the third oldest building in Manhattan after the Morris-Jumel Mansion in Washington Heights and St. Paul’s Chapel near the World Trade Center. In 1773 it was a fashionable two-story home for Rose, a successful lumber merchant, but its more colourful history came a century later, during the Civil War era, when it was the site an infamous saloon known as “Kit Burns’ Rat Pit,” run by one of the founders of the Dead Rabbits gang.

Today, the 1,424-square-foot unit shows few signs of its unsavoury past. Located on a cobblestoned side street, the building still retains its brick facade and original Georgian-style, but the upper floors were added after a fire in 1904, and the interiors were completely restored by architect Oliver Lundquist when the building was converted to condos in 1997.

The sellers, who purchased the unit for $1.575 million in 2022, listed the property with Lindsey Stokes and Allison Venditti of Compass on Tuesday.

When Rose built the home on Water Street, the isle of Manhattan was smaller, and the home had direct access to the East River where he docked his merchant ship, Industry . By the turn of the century the ground floor had been converted to commercial use, and it was used as an apothecary, a cobbler shop, a watchmakers’ shop and a grocery.

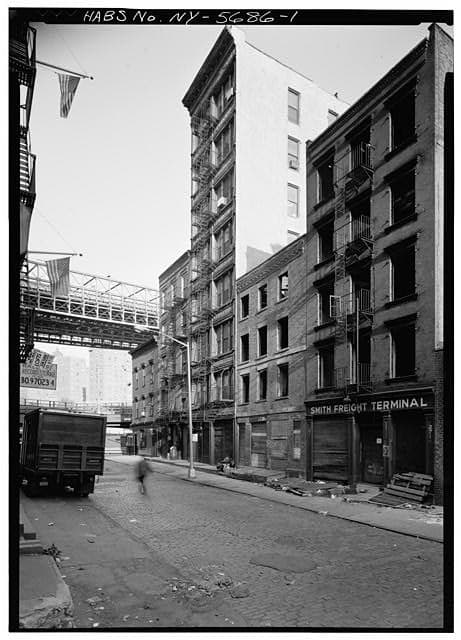

Library of Congress

By the 1860s, the bustling South Street Seaport had begun to decline as shipping lines moved to larger ports along the Hudson River, and the neighbourhood deteriorated. The Joseph Rose building was purchased by Christopher “Kit” Burns, who opened a saloon called Sportsman’s Hall, a den of vice most notable for its rat pit—the largest in the city—where Burns staged “rat baiting” events, in which caged dogs compete to kill rats while spectators bet on the outcome.

Journalist James W. Buel described Sportsman’s Hall in a book on American cities published in 1883. “This place was once an eating cancer on the body municipal,” he wrote. “Within its crime begrimed walls have been enacted so many villainies, that the world has wondered why the wrath of vengeance did not consume it.”

In 1870, the saloon was shut down by the authorities, and Burns leased the building to the Williamsburg Methodist Church, which used it as a refuge for women. Burns, meanwhile, opened a rat pit down the block at 388 Water St.

As the years progressed, the building suffered fires in 1904 and again in 1976, after which it fell into disrepair and was seized for unpaid taxes. In 1997, the city sold the neglected building to developer Frank Sciame Jr. for just $1, who restored it and converted it to luxury condos.

The upper unit has traded hands several times in the decades since. Currently, the unit begins with a foyer that leads to an open plan living and dining area on the main level, with a staircase leading to two bedrooms on the upper level, and a private rooftop.

After purchasing the unit, the sellers worked with designer Lauryn Stone to renovate the upper level, reconfiguring the floor plan and remodelling the primary bathroom, according to Stokes. The interiors feature finished white oak floors and painted brick walls, with built-in shelves and a ventless fireplace in the living room, stone counters in the kitchen, a walk-in closet off the primary bedroom, and two rows of six-over-six panelled windows adding light and air.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

A long-standing cultural cruise and a new expedition-style offering will soon operate side by side in French Polynesia.

The pandemic-fuelled love affair with casual footwear is fading, with Bank of America warning the downturn shows no sign of easing.

Weary of ‘smart’ everything, Americans are craving stylish ‘analog rooms’ free of digital distractions—and designers are making them a growing trend.

James and Ellen Patterson are hardly Luddites. But the couple, who both work in tech, made an unexpectedly old-timey decision during the renovation of their 1928 Washington, D.C., home last year.

The Pattersons had planned to use a spacious unfinished basement room to store James’s music equipment, but noticed that their children, all under age 21, kept disappearing down there to entertain themselves for hours without the aid of tablets or TVs.

Inspired, the duo brought a new directive to their design team.

The subterranean space would become an “analog room”: a studiously screen-free zone where the family could play board games together, practice instruments, listen to records or just lounge about lazily, undistracted by devices.

For decades, we’ve celebrated the rise of the “smart home”—knobless, switchless, effortless and entirely orchestrated via apps.

But evidence suggests that screen-free “dumb” spaces might be poised for a comeback.

Many smart-home features are losing their luster as they raise concerns about surveillance and, frankly, just don’t function.

New York designer Christine Gachot said she’d never have to work again “if I had a dollar for every time I had a client tell me ‘my smart music system keeps dropping off’ or ‘I can’t log in.’ ”

Google searches for “how to reduce screen time” reached an all-time high in 2025. In the past four years on TikTok, videos tagged #AnalogLife—cataloging users’ embrace of old technology, physical media and low-tech lifestyles—received over 76 million views.

And last month, Architectural Digest reported on nostalgia for old-school tech : “landline in hand, cord twirled around finger.”

Catherine Price, author of “ How to Break Up With Your Phone,” calls the trend heartening.

“People are waking up to the idea that screens are getting in the way of real life interactions and taking steps through design choices to create an alternative, places where people can be fully present,” said Price, whose new book “ The Amazing Generation ,” co-written with Jonathan Haidt, counsels tweens and kids on fun ways to escape screens.

From both a user and design perspective, the Pattersons consider their analog room a success.

Freed from the need to accommodate an oversize television or stuff walls with miles of wiring, their design team—BarnesVanze Architects and designer Colman Riddell—could get more creative, dividing the space into discrete music and game zones.

Ellen’s octogenarian parents, who live nearby, often swing by for a round or two of the Stock Market Game, an eBay-sourced relic from Ellen’s childhood that requires calculations with pen and paper.

In the music area, James’s collection of retro Fender and Gibson guitars adorn walls slicked with Farrow & Ball’s Card Room Green , while the ceiling is papered with a pattern that mimics the organic texture of vintage Fender tweed.

A trio of collectible amps cluster behind a standing mic—forming a de facto stage where family and friends perform on karaoke nights. Built-in cabinets display a Rega turntable and the couple’s vinyl record collection.

“Playing a game with family or doing your own little impromptu karaoke is just so much more joyful than getting on your phone and scrolling for 45 minutes,” said James.

Screen-Free ‘Escapes’

“Dumb” design will likely continue to gather steam, said Hans Lorei, a designer in Nashville, Tenn., as people increasingly treat their homes “less as spaces to optimise and more as spaces to retreat.”

Case in point: The top-floor nook that designer Jeanne Hayes of Camden Grace Interiors carved out in her Connecticut home as an “offline-office” space.

Her desk? A periwinkle beanbag chair paired with an ottoman by Jaxx. “I hunker down here when I need to escape distractions from the outside world,” she explained.

“Sometimes I’m scheming designs for a project while listening to vinyl, other times I’m reading the newspaper in solitude. When I’m in here without screens, I feel more peaceful and more productive at the same time—two things that rarely go hand in hand.”

A subtle archway marks the transition into designer Zoë Feldman’s Washington, D.C., rosy sunroom—a serene space she conceived as a respite from the digital demands of everyday life.

Used for reading and quiet conversation, it “reinforces how restorative it can be to be physically present in a room without constant input,” the designer said.

Laura Lubin, owner of Nashville-based Ellerslie Interiors, transformed a tiny guest bedroom in her family’s cottage into her own “wellness room,” where she retreats for sound baths, massages and reflection.

“Without screens, the room immediately shifts your nervous system. You’re not multitasking or consuming, you’re just present,” said Lubin.

As a designer, she’s fielding requests from clients for similar spaces that support mental health and rest, she said.

“People are overstimulated and overscheduled,” she explained. “Homes are no longer just places to live—they’re expected to actively support well-being.”

Designer Molly Torres Portnof of New York’s DATE Interiors adopted the same brief when she designed a music room for her husband, owner of the labels Greenway Records and Levitation, in their Lido Beach, N.Y. home. He goes there nightly to listen to records or play his guitar.

The game closet from the townhouse in “The Royal Tenenbaums”? That idea is back too, says Gachot. Last year she designed an epic game room backed by a rock climbing wall for a young family in Montana.

When you’re watching a show or on your phone, “it’s a solo experience for the most part,” the designer said. “The family really wanted to encourage everybody to do things together.”

Analog Accessories

Don’t have the space—or the budget—to kit out an entire retro rec room?

“There are a lot of small tweaks you can make even if you don’t have the time, energy or budget to design a fully analog room from scratch,” said Price.

Gachot says “the small things in people’s lives are cues of what the bigger trends are.”

More of her clients, she’s noticed, have been requesting retrograde staples, such as analog clocks and magazine racks.

For her Los Angeles living room, chef Sara Kramer sourced a vintage piano from Craigslist to be the room’s centerpiece, rather than sacrifice its design to the dominant black box of a smart TV. Alabama designer Lauren Conner recently worked with a client who bought a home with a rotary phone.

Rather than rip it out, she decided to keep it up and running, adding a silver receiver cover embellished with her grandmother’s initials.

Some throwback accessories aren’t so subtle. Melia Marden was browsing listings from the Public Sale Auction House in Hudson, N.Y. when she spotted a phone booth from Bell Systems circa the late 1950s and successfully bid on it for a few hundred dollars.

“It was a pandemic impulse buy,” said Marden.

In 2023, she and her husband, Frank Sisti Jr., began working with designer Elliot Meier and contractor ReidBuild to integrate the booth into what had been a hallway linen closet in their Brooklyn townhouse.

Canadian supplier Old Phone Works refurbished the phone and sold them the pulse-to-tone converter that translates the rotary dial to a modern phone line.

The couple had collected a vintage whimsical animal-adorned wallpaper (featured in a different colourway in “Pee-wee’s Playhouse”) and had just enough to cover the phone booth’s interior.

Their children, ages 9 and 11, don’t have their own phones, so use the booth to communicate with family. It’s also become a favorite spot for hiding away with a stack of Archie comic books.

The booth has brought back memories of meandering calls from Marden’s own youth—along with some of that era’s simple joy. As Meier puts it: “It’s got this magical wardrobe kind of feeling.”

Australia’s housing market defies forecasts as prices surge past pandemic-era benchmarks.

The megamansion was built for Tony Pritzker, heir to the Hyatt Hotel fortune and brother of Illinois Gov. JB Pritzker.