Even in Its Priciest Neighbourhoods, Buying in Rome Remains a Bargain

Compared with other luxury housing markets in Europe, buyers get more bang for their buck in Italy’s capital

Gianluca and Selene Santilli have all of Rome at their feet.

Their four-storey penthouse apartment in an early 20th-century villa sits atop a hill in the Italian capital’s Parioli district. With 360-degree views from sitting rooms and outdoor areas, the property provides glimpses of the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica, residential Parioli’s towering pine trees and the winding course of the Tiber River.

The 4,010-square-foot home has free-standing pavilion-like spaces that suggest an urban compound more than an individual apartment. Now, after nearly two decades in the custom-designed space, the couple have listed the four-bedroom unit with Italy/Sotheby’s International Realty. It has an asking price of $6.1 million.

A similar level of luxury in Milan, Italy’s financial and fashion capital, would cost a lot more, says Gianluca, a 67-year-old attorney. “Rome is cheap,” he says, of both the homes for sale and for rent.

Gianluca and Selene, a 64-year-old office manager, priced their home at just under $1,500 a square foot. In Milan, by comparison, a smaller three-bedroom, 2,750-square-foot unit in a decade-old high-rise, with lavish views and similarly upscale fittings, is listed for $6.445 million, or about $2,350 a square foot.

Roman-style luxury was once associated with the gargantuan villas of ancient emperors and the frescoed palaces of Baroque-era princes, but these days it conjures up another phrase: a bargain.

Affordable Luxury

Rome’s average home prices, as of August, were about $350 a square foot—less than Italy’s Florence and Bologna, and around a third less than Milan, according to Immobiliare.it, a real-estate website.

Prices in Rome peaked in 2007, and the city has been slow to encourage new development and investment, says Antonio Martino, the Milan-based real-estate advisory leader for PwC Italy. In Milan, on the other hand, an increase in supply has been outpaced by a greater increase in demand, he says.

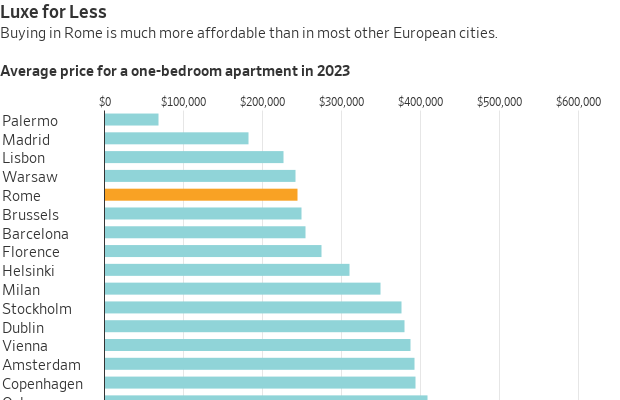

A one-bedroom apartment in Rome is far more affordable than the average for major European cities, coming in below Barcelona, Amsterdam and Vienna, according to an affordability index compiled by Savills, the international real-estate company, which analyzed apartments outside of the historic city centres.

An average-earning Roman might need only four years’ salary to buy the apartment, while a Parisian would likely need more than twice that, according to Savills.

Rome’s luxury sector is showing new signs of life, outpacing the rest of the market, says Danilo Orlando, managing director of Savills Residential Italy. Comparing 2023 sales of homes over $1.1 million with prepandemic 2019 levels, he says, prices in Rome have increased 4% while the number of luxury-level transactions has risen 3.6%. Overall real-estate transactions were up 3% in the second quarter of this year, compared with a year earlier, says PwC’s Martino.

Orlando says that residential luxury sales in Rome are traditionally concentrated in three nearby areas that are the city’s most expensive: The Centro Storico, or the historic center, is where centuries-old palaces are often broken up into lavish multi-bedroom apartments. Parioli is a hilly district known for its Midcentury Modern flare. And a short walk away is Trieste, which has clusters of early 20th-century apartment buildings that vie in splendour with their Baroque counterparts down in the centre.

Centro Storico and Trieste

Centro Storico is by far the most expensive, says Orlando, with average prices in the premium sector reaching $1,493 a square foot in 2023. Luxury units in Parioli average about $950 a square foot, while those in Trieste are about $900 a square foot.

Tourists may flock to Centro Storico’s celebrated sites, like the Trevi Fountain, or make their way through the Villa Borghese, a massive landscaped garden that serves as a green space for both Parioli and Trieste. But they are likely to miss the three districts’ prime residential areas, which can seem discreet, if not outright hidden.

Centro Storico’s Via Giulia, running just east of the Tiber, and Via Margutta, tucked under Piazza del Popolo, are hard-to-find streets if you’re not looking for them. Via Giulia was once the address of choice for Roman nobles, and it can still lay claim to being one of the city’s most prestigious streets. A two-bedroom Via Giulia triplex, located in a building dating back to the 16th century and outfitted with vintage coffered ceilings, is listed with Italy/Sotheby’s, with an asking price of $2 million.

The centrepiece of Trieste is the Coppedè quarter, a neighbourhood of towering 1910s and ’20s apartment buildings, decorated with Moorish arches and ghoulish gargoyles, and built around a storybook-like frog fountain. Conceived by an eccentric Florentine-born architect named Gino Coppedè, the quarter combines Art Nouveau elements with a range of historical styles.

Exclusive RE/Christie’s International Real Estate has a well-maintained, four-bedroom Coppedè listing for $3.56 million. Original details in the 3,770-square-foot home include stained-glass windows, mosaic tile floors and painted ceilings.

Parioli and Pinciano

Parioli, with its many steep streets, is a bit more remote, while Trieste is flatter and more urban. For many luxury-minded Romans, a fine compromise is Pinciano, a neighborhood beneath the heart of Parioli that is as rarefied as its hilly neighbour but as accessible as Trieste.

In 2007, Dr. Claudio Giorlandino, a Roman gynaecologist, created a sprawling family home in a Pinciano building that had been commissioned just before World War I, he says, by a member of the House of Savoy, then the Kingdom of Italy’s ruling family. Designed by a noted Venetian-Jewish architect and decorated with marble recovered from a Palladian villa in northeast Italy, the building has a small number of units, with Giorlandino’s 6,200-square-foot apartment taking up a whole floor.

“I love the elegance and the extremely refined, aristocratic atmosphere,” Giorlandino, now 70, says of his neighbourhood, which borders the Villa Borghese.

Now that two of his three children are grown and living on their own, he has listed the home with Exclusive RE/Christie’s for $6.89 million.

Rome’s three most expensive districts can seem like a self-contained world, with residents moving around between them. Giorlandino, who relocated from the Centro Storico to Pinciano, is now thinking about moving back to the historic centre. The Santillis, who moved to Parioli from Trieste, are considering looking for a more compact rental still in Parioli, which they say feels insulated from the Italian capital’s notorious traffic.

“We have the historic centre nearby, but we are not in the chaos of the centre,” says Gianluca Santilli, adding that he considers “the jewels” of his unique penthouse to be the home’s three parking spaces.

Vatican views

American buyers, traditionally drawn to the Centro Storico, are also open to Parioli and to the Aventine Hill, a very steep, purely residential area on the edge of the historic centre, says Diletta Giorgolo, head of residential at Italy/Sotheby’s.

Known for its jaw-dropping views of the Vatican and for its sedate, almost suburban quality, the Aventino, as Italians call it, may be Rome’s most elusive address. Premium listings rarely come up for sale.

Lionard Luxury Real Estate currently has a ¼-acre Aventino compound, with an early 20th-century 10,800-square-foot villa, listed for $22.2 million.

Mother-daughter apartments

A new Centro Storico development proved too good to pass up for Delphine Surel-Chang, a U.S.-born student studying business in Rome, and her French mother, former actress and investor Francoise Surel, who will also relocate.

The two are putting the finishing touches on their new homes in the Palazzo Raggi, where 21st-century details are being installed in a renovated 18th-century palazzo situated between the Trevi Fountain, Piazza Navona and the Pantheon. This summer, Surel purchased a 1,460-square-foot, two-bedroom apartment for herself, and Surel-Chang says her parents helped her buy a 645-square-feet one-bedroom. The units cost $1.88 million and about $944,000, respectively. They are set to move in later this year.

Surel-Chang, 20, says she loves how the project’s contemporary elements—which she and her mother, 60, are augmenting with kitchens and bathrooms from Italy’s sleek Boffi brand—are housed in a classical setting. And she appreciates amenities like a concierge and home automation, allowing residents to control temperature, lighting and appliances via app.

She was able to customise her unit’s interiors, she says, by drawing inspiration from her two favorite local hotels, the Bulgari Hotel Roma and Six Senses Rome. She plans to furnish the unit, where she says they will stay for at least three years, with Italian Midcentury Modern pieces.

The duo bought the apartments—which are a five-minute walk from Via Condotti, Rome’s premier shopping street—for between $1,200 and $1,500 a square foot, using Italy/Sotheby’s, which also helped develop the project.

The apartments can seem like a bargain compared with similarly situated units in other major cities. For instance, a two-bedroom, 2,025-square-foot apartment in London’s Mayfair district—a five-minute walk from Bond Street, Via Condotti’s U.K. shopping district equivalent—is asking nearly $10,000 a square foot.

Affordability played a part in their choice of the Eternal City, says Surel-Chang. They considered relocating to Paris, she says, but soon realised that “for the price of an apartment in Paris, we can afford two in Rome.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

A long-standing cultural cruise and a new expedition-style offering will soon operate side by side in French Polynesia.

The pandemic-fuelled love affair with casual footwear is fading, with Bank of America warning the downturn shows no sign of easing.

Weary of ‘smart’ everything, Americans are craving stylish ‘analog rooms’ free of digital distractions—and designers are making them a growing trend.

James and Ellen Patterson are hardly Luddites. But the couple, who both work in tech, made an unexpectedly old-timey decision during the renovation of their 1928 Washington, D.C., home last year.

The Pattersons had planned to use a spacious unfinished basement room to store James’s music equipment, but noticed that their children, all under age 21, kept disappearing down there to entertain themselves for hours without the aid of tablets or TVs.

Inspired, the duo brought a new directive to their design team.

The subterranean space would become an “analog room”: a studiously screen-free zone where the family could play board games together, practice instruments, listen to records or just lounge about lazily, undistracted by devices.

For decades, we’ve celebrated the rise of the “smart home”—knobless, switchless, effortless and entirely orchestrated via apps.

But evidence suggests that screen-free “dumb” spaces might be poised for a comeback.

Many smart-home features are losing their luster as they raise concerns about surveillance and, frankly, just don’t function.

New York designer Christine Gachot said she’d never have to work again “if I had a dollar for every time I had a client tell me ‘my smart music system keeps dropping off’ or ‘I can’t log in.’ ”

Google searches for “how to reduce screen time” reached an all-time high in 2025. In the past four years on TikTok, videos tagged #AnalogLife—cataloging users’ embrace of old technology, physical media and low-tech lifestyles—received over 76 million views.

And last month, Architectural Digest reported on nostalgia for old-school tech : “landline in hand, cord twirled around finger.”

Catherine Price, author of “ How to Break Up With Your Phone,” calls the trend heartening.

“People are waking up to the idea that screens are getting in the way of real life interactions and taking steps through design choices to create an alternative, places where people can be fully present,” said Price, whose new book “ The Amazing Generation ,” co-written with Jonathan Haidt, counsels tweens and kids on fun ways to escape screens.

From both a user and design perspective, the Pattersons consider their analog room a success.

Freed from the need to accommodate an oversize television or stuff walls with miles of wiring, their design team—BarnesVanze Architects and designer Colman Riddell—could get more creative, dividing the space into discrete music and game zones.

Ellen’s octogenarian parents, who live nearby, often swing by for a round or two of the Stock Market Game, an eBay-sourced relic from Ellen’s childhood that requires calculations with pen and paper.

In the music area, James’s collection of retro Fender and Gibson guitars adorn walls slicked with Farrow & Ball’s Card Room Green , while the ceiling is papered with a pattern that mimics the organic texture of vintage Fender tweed.

A trio of collectible amps cluster behind a standing mic—forming a de facto stage where family and friends perform on karaoke nights. Built-in cabinets display a Rega turntable and the couple’s vinyl record collection.

“Playing a game with family or doing your own little impromptu karaoke is just so much more joyful than getting on your phone and scrolling for 45 minutes,” said James.

Screen-Free ‘Escapes’

“Dumb” design will likely continue to gather steam, said Hans Lorei, a designer in Nashville, Tenn., as people increasingly treat their homes “less as spaces to optimise and more as spaces to retreat.”

Case in point: The top-floor nook that designer Jeanne Hayes of Camden Grace Interiors carved out in her Connecticut home as an “offline-office” space.

Her desk? A periwinkle beanbag chair paired with an ottoman by Jaxx. “I hunker down here when I need to escape distractions from the outside world,” she explained.

“Sometimes I’m scheming designs for a project while listening to vinyl, other times I’m reading the newspaper in solitude. When I’m in here without screens, I feel more peaceful and more productive at the same time—two things that rarely go hand in hand.”

A subtle archway marks the transition into designer Zoë Feldman’s Washington, D.C., rosy sunroom—a serene space she conceived as a respite from the digital demands of everyday life.

Used for reading and quiet conversation, it “reinforces how restorative it can be to be physically present in a room without constant input,” the designer said.

Laura Lubin, owner of Nashville-based Ellerslie Interiors, transformed a tiny guest bedroom in her family’s cottage into her own “wellness room,” where she retreats for sound baths, massages and reflection.

“Without screens, the room immediately shifts your nervous system. You’re not multitasking or consuming, you’re just present,” said Lubin.

As a designer, she’s fielding requests from clients for similar spaces that support mental health and rest, she said.

“People are overstimulated and overscheduled,” she explained. “Homes are no longer just places to live—they’re expected to actively support well-being.”

Designer Molly Torres Portnof of New York’s DATE Interiors adopted the same brief when she designed a music room for her husband, owner of the labels Greenway Records and Levitation, in their Lido Beach, N.Y. home. He goes there nightly to listen to records or play his guitar.

The game closet from the townhouse in “The Royal Tenenbaums”? That idea is back too, says Gachot. Last year she designed an epic game room backed by a rock climbing wall for a young family in Montana.

When you’re watching a show or on your phone, “it’s a solo experience for the most part,” the designer said. “The family really wanted to encourage everybody to do things together.”

Analog Accessories

Don’t have the space—or the budget—to kit out an entire retro rec room?

“There are a lot of small tweaks you can make even if you don’t have the time, energy or budget to design a fully analog room from scratch,” said Price.

Gachot says “the small things in people’s lives are cues of what the bigger trends are.”

More of her clients, she’s noticed, have been requesting retrograde staples, such as analog clocks and magazine racks.

For her Los Angeles living room, chef Sara Kramer sourced a vintage piano from Craigslist to be the room’s centerpiece, rather than sacrifice its design to the dominant black box of a smart TV. Alabama designer Lauren Conner recently worked with a client who bought a home with a rotary phone.

Rather than rip it out, she decided to keep it up and running, adding a silver receiver cover embellished with her grandmother’s initials.

Some throwback accessories aren’t so subtle. Melia Marden was browsing listings from the Public Sale Auction House in Hudson, N.Y. when she spotted a phone booth from Bell Systems circa the late 1950s and successfully bid on it for a few hundred dollars.

“It was a pandemic impulse buy,” said Marden.

In 2023, she and her husband, Frank Sisti Jr., began working with designer Elliot Meier and contractor ReidBuild to integrate the booth into what had been a hallway linen closet in their Brooklyn townhouse.

Canadian supplier Old Phone Works refurbished the phone and sold them the pulse-to-tone converter that translates the rotary dial to a modern phone line.

The couple had collected a vintage whimsical animal-adorned wallpaper (featured in a different colourway in “Pee-wee’s Playhouse”) and had just enough to cover the phone booth’s interior.

Their children, ages 9 and 11, don’t have their own phones, so use the booth to communicate with family. It’s also become a favorite spot for hiding away with a stack of Archie comic books.

The booth has brought back memories of meandering calls from Marden’s own youth—along with some of that era’s simple joy. As Meier puts it: “It’s got this magical wardrobe kind of feeling.”

Micro-needling promises glow and firmness, but timing can make all the difference.

The era of the gorgeous golden retriever is over. Today’s most coveted pooches have frightful faces bred to tug at our hearts.